The Supreme Court of Maryland revisited a century-old decision that barred a Black man from becoming a lawyer despite him meeting all the qualifications all because he was Black. The Court (finally) granted him posthumous admission to the state bar after receiving a petition on the man’s behalf.

Why did it take so long? Keep Reading

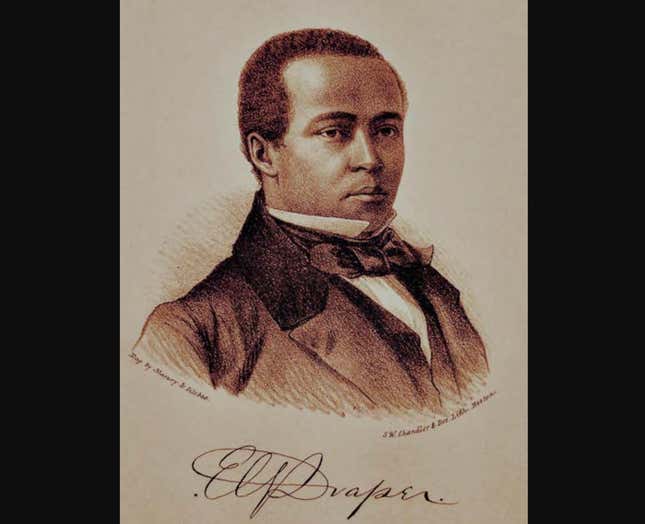

During the 1850s, Maryland bore an abolitionist movement but tussled with the rights of Black folks in the court system as they fought for their freedom and equal rights. By 1857, the United States Supreme Court ruled in the Dred Scott decision that Black people were not entitled to citizenship. However, Edward Garrison Draper dared to pursue a career in the legal system.

The born free Darmouth graduate presented himself before the Baltimore Supreme Court having studied law for two years under another attorney, according petition writers Justice John G. Browning, attorney Domonique Flowers and University of Baltimore School of Law professor José Anderson. Judge Zachaeus Collins Lee - cousin of infamous slave owner Robert. E Lee - adored Draper. He said he was “most intelligent” in his responses to questions and “qualified in all respects” to be admitted to the bar.

Though, Lee said there was only one disqualification: Draper’s skin color.

Read more from the petition:

Until passage of its bar admission statute in 1832, no formal standards existed for becoming a lawyer in Maryland. Before the Civil War, there were only handful of law schools in the United States, none of which were in Maryland. Most lawyers in the United States received their training by “reading the law” under the tutelage of an older practitioner or judge. Even late in the 19th century, college degrees were not common; as late as 1883, less than half of the students at the fledgling University of Maryland School 0f Law had bachelor’s degrees.

With the 1832 statute, Maryland spelled out that an applicant for admission must be free male citizen of Maryland over twenty-one years of age who had been “a student of the law in any part of the United States, for at least two years previous to said application.” In addition, the statute specified that an applicant had to be white.

After being denied admission, Draper traveled overseas in hopes to emigrate to Liberia and practice law there, with a handwritten certificate from Judge Lee to do so. However, Draper died the year he arrived from tuberculosis. We’ll never know the impact he would have had as Maryland’s first Black attorney but his posthumous admission makes an attempt to right the wrong.

“But by granting posthumous bar admission to Edward Garrison Draper, this court places itself and places Maryland in the vanguard of restorative justice and demonstrates conclusively that justice delayed may not be justice denied,” wrote Browning.