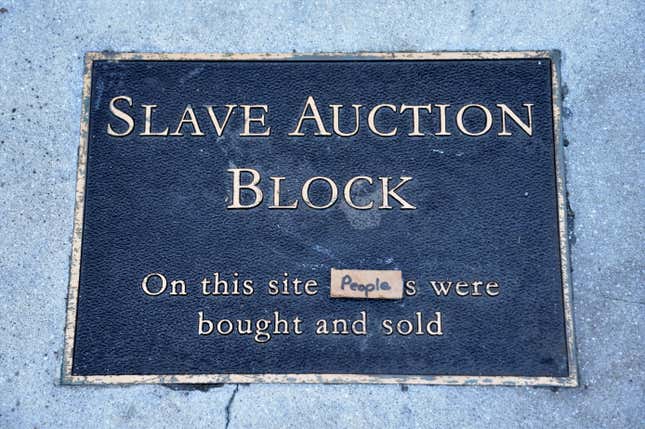

When a plaque disappeared off a sidewalk in Charlottesville, Va., earlier this month, it raised alarm bells. The sign, though small, was significant: It marked the site of an auction block where enslaved Africans were sold.

As The Washington Post reports, some assumed it was done to protest a proposed state law that would allow cities to remove offensive monuments. Others thought it was an act of racist vandalism.

It was an act of protest from a white man—but not for the reasons people may have suspected. Richard Allan, a 74-year-old amateur historian, dislodged the plaque because he thought the site deserved a more prominent memorial.

He publicly confessed to C-Ville.com, admitting that he headed to Court Square at about 2:45 am and used a wonder bar and a kitchen knife to pry up the marker.

“It took about 15 minutes,” he says.

Allan first heard about the plaque in 2014, after reading a letter to the editor in a newspaper from Eugene Williams, a local civil rights leader. Williams criticized the removal of a prominent sign marking the historic site, noting that the sidewalk plaque that replaced it was “almost invisible.”

Allan ended up meeting Williams to discuss the issue, befriending the activist in the process. He also did his own research into the plaque.

From the Post:

Allan took his research further, interviewing officials and even the owner of the building from which the original sign was removed. In a report published in a local paper later that year, he said the more prominent sign was taken down because the building’s occupants were annoyed at tourists asking them about the site’s history of slave auctioning.

Two months after the deadly Unite the Right rally in the city in August 2017, Allan asked city officials whether they had plans to improve the memorial, but received only a terse response from then-Vice Mayor Heather Hill.

The tipping point came when Allan met Richard Parks earlier this year. A 68-year-old retired social worker and artist, Parks (who is also white) was equally offended by the sign’s placement.

“People could walk in dog shit and then step on that plaque,” Parks told The Post. “While you’ve got these 30-foot high monuments to the people who fought and died for slavery right down the block.”

Using chalk, Parks would cross out “slaves” and write “human” or “people” on the plaque, as well as placing flowers and signs by it so it could draw more people’s attention. He also showed Allan a small crowbar he was thinking about using to dislodge the sign but wasn’t sure if he would follow through.

Allan, instead, chose to go through with it. Shortly after the plaque was taken, Parks replaced it with a handmade one:

“HUMAN AUCTION SITE,” the first line read. “In 1619 the first African kidnap victims arrived in VA. Buying and selling of humans ended in 1865. For 246 years this barbaric trade took place on sites like this.”

Since confessing to the crime—and being released by the police—Allan has remained unrepentant. A professed descendant of slave-owners, Allan views the act as a way of addressing, head-on, a historic wrong.

From the Post:

“How would you feel if they put a plaque in the ground to you so people could stand on it with their dirty shoes?” he told The Washington Post on Monday, adding that he was trying to atone for the fact that his own ancestors had owned slaves.

“This is called reparations, as far as I’m concerned,” he said when asked if he was willing to go to jail.

...I did this,” he said, “to stop the erasure of history.”

But Charlottesville Police Chief RaShall Brackney says it simply wasn’t Allan’s place to act unilaterally to improve a site of public memory.

“We have an individual who announces that their family was, in fact, slave owners. Once again, his family and his privilege has decided how those slaves and their descendants would be honored,” she said.

While police are still investigating the theft, Brackney, who is black, noted that evaluating the motivation of Allan’s crime is a matter best left to a judge or jury.

“Although he may have thought it was offensive for people to be able to walk on this plaque, those kinds of markers remind us that slaves were often walked on in life. The plaque may actually be more powerful where it’s positioned,” Brackney said. “That’s not for me to decide.”