My grandmother had a “pork pan.”

In 1954, my grandfather built the house I lived in for most of my life. And for all of my life, there was a single cast iron skillet that was dedicated to frying bacon, bologna with the red plastic ring, or any part of a pig. Everyone in my family knew this rule—even my aunts and cousins who came to visit. While this revelation may seem funny to you, there is a good reason why it was always so weird to me:

No one in my family eats pork.

For religious reasons, my grandparents didn’t eat pork, nor did any of my aunts, uncles or cousins. They were so strict about it, they wouldn’t even eat out of pots that pork had been in unless they inspected it first. And, because I was raised by them, I didn’t eat pork either. Because of this, all of my aunts, uncles and cousins have a “pork pan” at their house, which is weird for people who don’t eat pork. I guess it’s just a thing we passed down.

I also can’t eat milk or cheese. I’m not lactose-intolerant; my stomach can’t even digest it. For lack of a better way to describe it, if I swallow even a smidgen of cheese, it comes right back up.

Here’s the thing: For most of my life, I was ashamed to tell people about it because, like most kids, I just wanted to blend in and go unnoticed. Whenever my vacation Bible school camps served those shitty ham and cheese sandwiches or my friends went out for pizza, I’d just wait to eat until I got home. Only my closest friends knew, and only because they realized I wasn’t thrilled when it was pizza day at school and they could always get my carton of milk.

So instead of hanging out at pizza places, my closest friends would go get wings. Still, to this day, I’ll go to a cookout with someone who knows me well and they’ll tell the cook: “Do you have something that Mike can eat? He doesn’t eat pork.” Once, during a crowded late-night excursion to Waffle House, one of my more intimidating pharmaceutical entrepreneurial friends gave a short-order $40 cook to clean the bacon grease off of the grill before he made my hash browns.

That’s all.

Where did all these anti-racist white people come from?

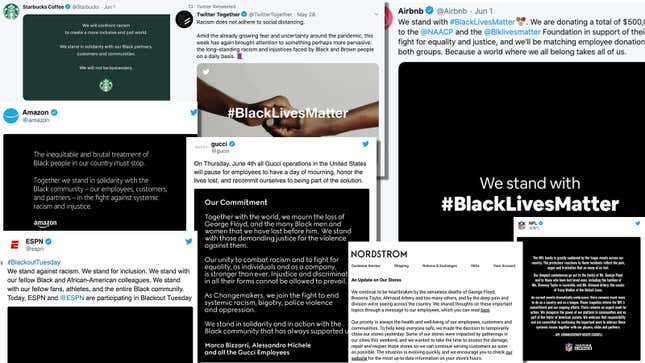

Since the beginning of the George Floyd protests, white people have come out of the woodwork with statements declaring their disdain for inequality and their willingness to stand against racism.

But this meaningless, performative show of solidarity is not just limited to companies and brands. All of a sudden, white people are ready to take a stand against racism after saying nothing about it for years.

I’m torn about this.

Part of the reason that racism persists is that white people don’t do anything about it. They don’t challenge their friends, challenge their family members, or reprimand their coworkers when they see racism. They might hate inequality but do nothing to fight it.

Racism is a fire and the only difference between an arsonist and a pyromaniac is the act of igniting the flame. If you stand idly by and watch flames consume a house, you’re still part of the problem. It is not enough to not be racist if you don’t do anything about it.

On the other hand, white people are fragile.

When white people engage in performative protest, should they be reprimanded? For instance, if a certain writer at The Root drags Taylor Swift for not speaking up about her white supremacist supporters because she didn’t “have the internet on her phone,” will calling out her newfound wokeness make her more reluctant to call out racism?

If we want white people on our side, do we get to be the arbiters of their intent? Is using their platform to speak out against racism enough, or should we chastise them for not doing more?

If someone who knew about my aversion to pork invites me to dinner, I wouldn’t be upset if they didn’t inform the cook about my eating habits. It happens all the time. I don’t think anyone has a responsibility to think about my dietary restrictions, even if they are aware of them. I grew up in a place where everyone eats chitlins and barbecue, so I’m used to it.

I’m also used to racism.

I don’t think most white people are racists. I think most white people don’t think about race because they don’t have to. For them, privilege is a delicious dish they get to enjoy whenever they want it and even though they know some people can’t stomach racism, they don’t think about it when it is served up on a platter to their coworkers and associates.

Being white in America is like being at a 24-hour, 400-year company dinner party where everything that comes out of the kitchen is delicious, at best, and— at the very least—personally edible.

Like privilege.

Like whiteness.

It’s not that white people don’t care about their friends. It’s that they don’t think about racism. White people are immune to white supremacy so they don’t even consider that some of us are racism-intolerant.

To be black in America is a neverending task of considering all the ways we might be forced to consume racism when it’s served to us. When you’re hungry, you nibble around the edges like a vacation bible school sandwich. Sometimes you just swallow it and smile, knowing it’s gonna make you sick. The most intolerant among us just try not to vomit.

My family loves to cook for people.

I suspect part of the reason why they love it is that they don’t have to think about what they have to avoid eating. We look for any reason to host large dinners and invite over the entire neighborhood.

A few years ago, when my kids were kids, they spent half the summer with their cousins in Virginia and their cousins spent half the summer with them. When I picked up the kids and the cousins and their grandmother for the 9-hour trip, I called my aunt, who hadn’t seen them in years, and told her we’d stop by. Because she lived basically at the halfway point of the trip, I figured we could eat, rest, and she’d get to see them. She told me she would prepare some food.

By the time I got to her house, she had essentially prepared an entire buffet of every southern delicacy you can imagine. She had called every relative, church member and family friend and there were no less than two dozen people eating.

She was still cooking when I arrived, preparing to fry some pork chops, so of course, I helped out in the kitchen. As she prepared to fry some pork chops, she told me to get the pork pan:

“Marvell, none of us even eat pork,” I said. “Why does everyone in the family keep a pork pan?”

“Mr. Elmore bought that pork pan for Daddy,” she replied, speaking of my grandfather who died before I was born. “That’s what we made the sandwiches in...for the protests.”

I knew part of this story because everyone loved Mr. Elmore.

During the sit-ins and protests during the 1950s and ’60s, one of the ways my town tried to kill the protests was to literally ban people from the entire business district in our small town during protests. So when local churches organized sit-ins or a protest, once a demonstration started, they couldn’t leave the downtown area for food or water. They couldn’t even walk down a nearby street.

But my grandfather owned the only little black cab company in town and was permitted to go anywhere. And, because he was permitted to travel anywhere in town, whenever there was a protest, he would just fill his trunk with sandwiches, go downtown, leave his trunk ajar during the stop, and one of the protesters would sneak into his trunk and get jugs of water and grocery bags filled with sandwiches.

The interesting thing about this was that all the food was supplied by a local grocer, Mr. Elmore. I’m not quite sure if Mr. Elmore owned the Piggly Wiggly or just managed it, but he always hired black workers and would always give food to anyone who needed it. To this day, I still can recite the number to the Piggly Wiggly.

My aunts, uncles and the entire household would be in charge of assembling these sandwiches made from whatever meat Mr. Elmore donated. Sometimes it was bologna. Sometimes it was beef. And the best day to protest was when Mr. Elmore gave away pork chops. And because he knew of my family’s diet (we shopped at his store all my life), Mr. Elmore even gave my grandfather a cast iron pan to fry the swine.

It is also not clear if Mr. Elmore kept this quiet so he wouldn’t upset his white customers or because he didn’t need people to know he was helping desegregation efforts, but two things were well known among my town’s black community.

- Mr. Elmore was an ally.

- My grandmama could fry the hell out of some pork chops.

My aunt didn’t tell me this story in the kitchen that day. I had always known most of it (even that he was the originator of the pork pan). The reason I knew this story was because of one reason:

I used to hate Mr. Elmore.

On the first of the month, when my grandmother got her pension and her Social Security check, my grandmother would fry two pork chop and send me to the Piggly Wiggly with a greasy Piggly Wiggly bag. (My family still calls any grocery bag a “Piggly Wiggly bag.”) I would cash her check, buy her a pair of stockings for church and hand Mr. Elmore two pork chop sandwiches.

I never knew why it was our responsibility to feed this white man. He wasn’t doing us any favors. He still charged us full price! I couldn’t understand why every black person in town shopped at the Piggly Wiggly when there were stores closer to our neighborhood. Plus, he knew we didn’t eat pork so why was he getting negroes to bring him food like he was a slavemaster?

When Mr. Elmore died, there were probably more black people at his funeral than white people. My entire family attended, even my aunts and uncles from out of town. It was weird because it was a very white funeral and only white people spoke but it was held in the biggest black church in town.

After the funeral, all the white people left but, of course, the black people convened in the church cafeteria and the black attendees actually gave speeches at the repast as if they were revealing a secret that everyone knew but found it unnecessary to say out loud. Almost everyone referred to him as a “friend of the black community.”

My grandmother ambled out of the church kitchen at some point and told the story of Mr. Elmore’s pork chop protests. The old people nodded in agreement as she recounted his quiet activism. They smiled when she recounted how she would lie to everyone when they called and asked what Mr. Elmore had brought for the protests. They laughed when she recounted how she always lied and told people she was frying pork chops because more people would come out. She even used a word that wasn’t en vogue back then (the early ‘90s) but is ubiquitous on social media these days.

She called him an “ally.”

By the time it was over, I was starving because I didn’t even get any of the usual repast food. None of my family members had a chance to eat that day because we were helping my elderly grandmother in the kitchen for the wokest white man no one ever knew.

She served pork chops.

She used the pork pan.

That’s all.