Sometimes, “a seat at the table” just means “sit there and make us look good while we pick your brain, exploit your culture and give you little to no credit.” At least, that’s what Kerby Jean-Raymond, designer and founder of Pyer Moss and a creative director at Reebok is alleging of fashion analysis and news site Business of Fashion (BoF), which recently included the CFDA Award-winning designer in its annual “Business of Fashion 500” list of most prominent influencers in the industry—not unlike The Root 100, a list Jean-Raymond also made this year. (Editor’s Note: As The Glow Up regularly cites BoF for fashion news, this article is not an indictment of their industry reporting.)

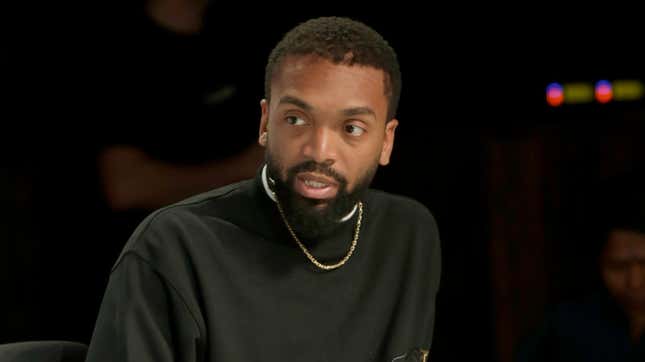

In an essay published on Medium titled “Business Of Fashion 500 is now 499,” on Tuesday, Jean-Raymond called out the site and its British-Canadian editor and founder Imran Amed for its treatment of him, other black influencers and black culture before and during the annual BoF 500 gala on Monday, September 30.

After presumably first addressing the issue in an Instagram story or now-deleted post, Jean-Raymond’s scathing missive chronicled what can only be described as a pattern of disrespect—however willfully oblivious—by Amed, in particular. It read, in part (condensed for brevity):

Last year, I was invited to speak at and attend BoF Voices [conference in London]. I was told they wanted to hear my story of the formation of [Pyer Moss] and how I’ve navigated the industry. As an outsider for so long, I was proud to be invited and get to share my story. I saw it to be like a fashion version of TED. I was also excited that I’d be in a solo conversation with Bethann Hardison. I had stopped doing group panels.

My reason is that so many of these group panels just lump us all in, ‘Black in Fashion’ or ‘Diversity & Inclusion’ when the reality is my family is vastly different, making strides in every category — sustainability, politics, VC… But instead they make us speak all together in the commonality of our blackness and force us to disagree on stages in public, facilitate infighting and then we have to do the emotional labor to make the ops comfortable.

So I agreed to do this solo panel..then at the very very last minute, like while I’m on the flight, they told my team that it was now a group panel. (Their plan all along.)...Because of my immense respect for Patrick [Robinson, former creative director of Gap and Armani Exchange], and LaQuan [Smith] as designers who like me are black, I did it, begrudgingly. But in reality all three of us have our own unique narratives and histories that warranted our own separate solo stages. The same solo stages that all the other white designers have received, for years...

A few months after that...Imran reaches out to me and asked to get on a call and talk...He said he’d seen the work I’d been doing with Pyer Moss and in the community and I’d been selected to be on one of the 3 covers of the BoF 500 magazine...So this now began a series of phone calls between him and I and meetings in Paris...In all these calls and talks he’s picking my brain for names to include on this cover with me and a list of “diverse” people for the 500...I figured this is a cover story slated for September, so we can talk openly.

After our last meeting, he looked satisfied with the information he’d received...Then he hits me with this text like really soon after that meeting saying “we are going to go a different route with the cover”…

After landing on the 500 list, Jean-Raymond reluctantly accepted an invitation to this year’s gala in Paris. Arriving late on Monday, he was disgusted to find a black choir performing for the predominantly white audience.

“[T]hen Imran gets on the mic and says something along the lines of ‘I want to just shout out a few people who inspired us to focus our issue on Diversity and inclusion’ and calls out a list of names, maybe 20 names,” Jean-Raymond wrote, adding that despite his extensive conversations with Amed, his name was not among them.

“To have your brain picked for months, be told that your talk at the “Salon” and work inspired this whole thing, and then be excluded in favor of big brands who cut the check is insulting,” he said, before recounting what he considered the final insult.

Then the choir comes back on stage. This man, Imran, turns into Kirk Franklin and starts dancing on the stage with them and shit. To a room full of white people. So now we at 90%. ...Because ultimately that level of entitlement is the core issue. People feeling like they can buy or own whatever they want … if that thing pertains to blackness. We are always up for sale.

So now we’re here. In short, fuck that list and fuck that publication. I take no ownership of choirs, Christianity or curating safe spaces for black people. That’s a “We” thing.

Homage without empathy and representation is appropriation. Instead, explore your own culture, religion and origins. By replicating ours and excluding us — you prove to us that you see us as a trend. Like, we gonna die black, are you?

Addressing Amed directly, Jean-Raymond then questioned the editor’s integrity and intent in what he clearly feels to be an exploitation of his intellectual capital and black culture, as a whole.

“I’m offended that you gaslighted me, used us, then monetized it and then excluded us in the most disrespectful way to patronize companies that need ‘racist offsets,’” he wrote. “And I’m offended that you all made those beautiful black and brown people feel really terrible to the point where some of my friends said ‘this is helpless’, ‘this shit will never change’ and others left in tears. I was fine until they weren’t fine. So I hit 100%.”

But really, what else is new? Jean-Raymond’s experience—albeit occurring in the upper echelons of the fashion industry, where one thinks one has “made it,” should they arrive there—echoes the appropriation and callous disregard we see daily from the luxury fashion industry and its influencer culture, both of which have riffed on everything from cornrows to blackface and other racist tropes in the name of high style.

Why should that lack of boundaries and exploitation not extend to the cultural cachet and capital of our best and brightest in the fashion industry? This is not to fault Jean-Raymond, who readily admits he is breathing rarified air, air he has repeatedly used to breathe respect and reverence back into our culture and history, whether the fashion industry finds it trendy or not. But forgive us if we’re not at all surprised.

“For a lot of people, we are the only peek they get behind the curtain of an industry they want to be a part of,” he wrote. “I have let a lot of shit slide because I do think a lot of problems can be resolved without public provocation. I typically prefer not to be blacklisted. I hate being the only one that talks up. I also enjoy peace.

“But — me getting checks is not going to stop me from checking you,” he added.

In response, Amed published his own op-ed in Business of Fashion on Tuesday morning, titled: “Why I’m Listening to Kerby Jean-Raymond” (please note that Amed clearly seems to consider this optional; a concession, even). In it, he points out that as the gay “son of Ismaili Muslim immigrants to Calgary, Canada from Nairobi, Kenya, I was also the only brown kid in my class,” as evidence that he himself is marginalized. He also writes:

Kerby has every right to voice his concerns and we respect his perspective. He is also right about several things. As Kerby points out, the fashion industry has often treated inclusivity as a trend, putting diverse faces in our ad campaigns, on our runways, on our magazine covers and, yes, at our parties because it’s cool and of the moment. But I can assure you that this topic is not a trend for BoF.

When we decided to focus our latest print issue and accompanying BoF 500 gala on inclusivity, we did so precisely because a superficial approach to inclusivity is indeed insulting — and wholly insufficient. The industry needs to go further and invest in the difficult work of genuine cultural change, and our issue is focused on going into this topic in-depth, from a variety of vantage points addressing the topics of race, ability and LGBTQIA+...

Amed goes on to discuss the diversity of BoF’s staff and somewhat cringingly list a number of black attendees at Monday night’s gala, as well as justify the black choir by referencing his own history in choir and musical theater. And yes, he does manage to apologize to Jean-Raymond, expressing his desire that the two become “allies” in diversifying the industry.

I am deeply sorry that I upset Kerby and have made him feel disrespected. While we may disagree in our opinions on the gala and the details of our exchanges over the past year, Kerby has my complete respect and I would appreciate the opportunity to sit down with him and learn more about his concerns and how we at BoF can do better, especially as we try to address important topics like inclusivity. While we will not shy away from addressing challenging topics, I am committed to making this a listening and learning opportunity for myself and BoF.

But why do we get the feeling y’all still don’t hear us, though?

Whether or not this really proves to be a teachable moment for BoF remains to be seen; clearly, there is much work to be done. But to Kerby Jean-Raymond: If you want an opportunity to speak—solo—to those who can perhaps appreciate and relate to it most, we’ve got a mic for you at The Root 100 gala, on Nov. 21.