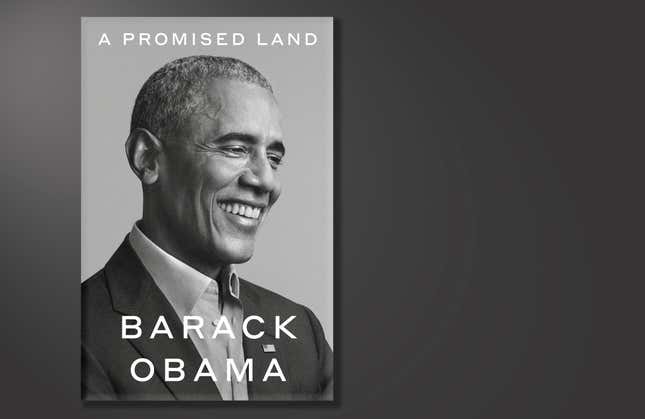

Because he’s been pretty low-key about it, you might not be aware that a promising politician that we’ve been keeping an eye on released A Promised Land on Tuesday—a book that offers a firsthand account of Barack Obama’s journey to becoming America’s first Black president.

When The Root discovered this information, we thought we’d help the little-known former senator overcome the lack of media coverage. It wasn’t that we were impressed by his ability to type complete sentences that didn’t contain the words “powerful” or “bigly.” However, after the success of Michelle Obama’s Becoming, we just didn’t want the rest of the Obamas to refer to the former president’s fourth literary offering as “his lil’ book or whatever.”

To help get the word out, Mr. Obama agreed to answer a few of my/The Root’s questions looking back on the Obama years and the time that followed. Here are his unedited responses.

Up until the day you won, even the concept of a Black president was an almost laughably unthinkable goal. What is the one thing that convinced you that you were the person who could do it?

Well, I wasn’t sure I was the person who could do it. Who knows, right? When you run for president, it’s a long shot, even if your name isn’t Barack Hussein Obama.

But here’s what I did know: That if I won, the day I raised my hand and took the oath to be president of the United States, the world would start looking at America differently. And kids all around the country—Black kids, Hispanic kids, kids who don’t fit in—they’d see themselves differently. Their horizons would be lifted, their sense of what was possible expanded. That, alone, was reason enough to give it a shot.

And I also thought about the civil rights generation of heroes: Dr. King, John Lewis, Ella Baker, Fannie Lou Hamer, C.T. Vivian, Dorothy Height, and so many others. They were the ones who made it possible for me to have the luxury of even considering running. And that’s why when that day came—and I raised my hand on the steps of the Capitol—I told John Lewis I was there because of him.

Which policy or policies of the Obama administration do you believe had the most impact on the lives of Black Americans?

Here’s the big picture: I’m proud of the work we did to lift Americans’ prospects across all races. And after entering office in the middle of a huge recession, we righted the ship with the economy, put folks back to work, and became the first administration to pass comprehensive healthcare reform after decades of trying. And because Black communities are often harder hit by many of these large-scale trends—inequality, joblessness, lack of health insurance—these interventions can have a real effect.

More specifically, we brought Black unemployment down from close to 17 percent when I became president to less than 8 percent when we left. We made sure healthcare was not a privilege for a few but a right for everybody—and secured coverage for 20 million Americans, including nearly three million African Americans. After my eight years in office, our high school graduation rate was at an all-time high, including for Black students. Obviously, we still had more work to do when I left office, and that’s still clear today on these and so many other issues.

As the millions of Americans who’ve raised their voices this year show, our criminal justice system is still broken. But we did begin to bring about some change during my two terms—reducing the federal prison population, ending the use of solitary confinement for juveniles, and banning the box for federal employers. We also reinvigorated the Justice Department’s civil rights division and created a twenty-first-century policing task force that brought together Black Lives Matter activists, police chiefs, academics, and others to come up with recommendations to make sure the law is applied equally across communities. And through My Brother’s Keeper, we brought new opportunities to young Black men across the country. I was particularly proud of the fact that, in my last year in office, we lifted millions of people out of poverty.

Now, a lot of the progress we made has been under assault the past few years, and this pandemic has hit Black folks especially hard. Which is why, even though this election is over, we can’t stop making our voices heard on the streets and at the polls, so we can realize the change we still need to make.

Looking back on your first presidential campaign, which political event or incident do you point to and say: “If this had or hadn’t happened, I would have never become president.”

Well, every winning campaign looks like it’s run by geniuses, but the truth is, there are always a bunch of events that could go either way. What matters is how you respond to them.

I first learned this during my campaign for Senate in 2004—when a series of events you definitely don’t have the time for me to go into sort of cleared the field for me. And then, when John Kerry asked me to speak at the 2004 Democratic convention, that was another pivotal moment, because it gave me a big platform to introduce myself.

The presidential campaign had too many events like that, too many inflection points, to list. But one thing that shaped my candidacy, which definitely didn’t feel like a blessing at the time, was how talented my opponents were in the primary. Going through that grueling process to become the nominee made me a better general election candidate and a better president.

Of course, there was the moment when people seized on some remarks my former pastor had made. That was painful. But it also gave me a chance to speak honestly about race in a way I think a lot of Americans found refreshing in a presidential candidate.

Then, during the general election, obviously, the biggest event was the financial crisis. Six weeks before the election, the bottom really fell out of the economy—and I wanted to make sure that I acted in such a way that folks would start seeing me not just as a candidate but as a president.

How did being a Black person in America prepare you for being president?

To be a good president you have to understand what folks are going through (and that’s a big part of the reason why I know my friend Joe Biden is going to be such a good one). The point is, issues can’t be purely theoretical—you’ve got to have some lived experience, to understand what’s going on in Black families, the kinds of conversations that are taking place, rather than just understanding our communities as another line of data on a chart.

My time as an organizer on the South Side of Chicago was particularly formative in this way. It’s an experience that gave me a firmer footing not just in my own racial identity but also in the common threads that unite us all, as Black folks and as Americans, even as there is no single way to be Black. I came to love the men and women I worked with back then—the single mom living on a ravaged block who somehow got all four children through college, the laid-off steelworker who went back to school to become a social worker. Through them, I saw the transformation that took place when citizens held their leaders and institutions to account, even on something as small as putting in a stop sign on a busy corner or getting more police patrols.

So I learned more about not only the lives and stories of folks on the South Side but also the promise and struggle at the heart of our democracy. It’s something I kept with me each day as president: that I couldn’t be satisfied simply seeing things through my own lens; I had to make sure I was thinking about what others are seeing and feeling, as well.

You are a former president and you are unquestionably the predominant role model for a generation of Black people, both of which come with a certain amount of public scrutiny. But for one day, you get to be an anonymous, everyday American who can go anywhere you want and do anything. Describe that day.

You know, honestly, I’d just take a walk. Go to the grocery store. Go out to dinner with Michelle. Maybe get some ice cream. Around my second or third year in office, I’d have this recurring dream, maybe once every six months, where I’m walking down the street and head into a coffee shop or a bar or something and nobody recognizes me. It was great!

What I really miss most are the virtues of anonymity. It’s not so much a security issue as it is the tyranny of selfies. Don’t get me wrong, people could not be nicer, and I love having a cool conversation. One of my favorite parts of campaigning, which I also miss, was being able to go into people’s living rooms, meeting them on their front porches, and they’d tell me about their lives. But I’m not about the selfies.

I guess that’s a high-class problem to have. As a friend once told me, it’s just the price of living out your dreams, which is a pretty good way of looking at it.

A Promised Land is available at Black-owned bookstores everywhere.

...And probably some white ones, too.