“Because I said so...”

Growing up in predominately Black skin, I heard that phrase a lot. My grandmother, aunts, uncles and friends’ parents used it all the time. But my mother was always careful to never use it. She had this weird thing about wanting us to know why we did things.

My grandfather owned a taxicab business, so before my sisters, cousins and I could ever get behind a steering wheel, we had to learn how to jump-start a car; how to check all the fluids; how to change the oil and, of course, how to change a tire. Because my mother was blind, we didn’t even own a car. But one day when I was 11 or 12 years old, riding to church with my aunt, we had a flat. My mother insisted that this was the time for me to learn how to change a tire.

I’m on the grassy edge of a two-lane highway in church clothes, tools in front of me as my mother leaned over me like an over-enthusiastic test proctor. Instead of giving me instructions, she employed her usual Socratic Method to teach me how to change the tire. Back in those days, cars used these old vintage jacks, which I had seen people use many times:

I began assembling the jack when she interrupted me.

“Why are you doing it like that?” she asked.

“I’ve seen people change a tire before, ma,” I replied. “This is how it goes.”

“But how do you know that’s how it goes?” she asked again.

“Because this is what everyone I’ve seen change a tire does,” I sighed.

She leaned over a bit more. I can’t remember whether it was hot or cold but I clearly recall that she blocked out the sun. It seemed like she was trying to intimidate me but, looking back, I damn near forgot that she is legally blind. Regardless, I just wanted to get to church. Everyone was out of the car watching and waiting for my mama to finish her impromptu automotive school lesson. Why was she like this?

“Ummm Hmm,” she said absentmindedly before half-whispering the life lesson that has stuck with me more than any other.

“But what if everyone else was doing it wrong?”

This is the Clapback Mailbag.

This week, Senior Reporter Terrell Starr wrote this:

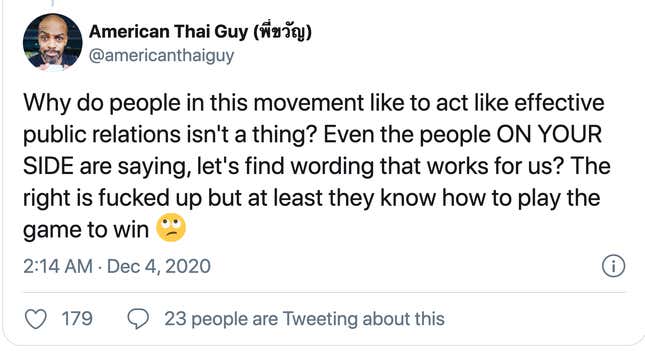

The article prompted a lot of comments, especially about the “Defund the Police” slogan.

From: JYStad

To: Terrell StarrWhoever named it “Defund the Police” killed that baby in the crib. They could have called it Police Budget Reallocation/Reapportionment or literally ANYTHING that did not sound like it completely deprived police of *all* their funding. If we learned anything from Lovecraft Country or even Spirited Away, there is power in a name, and christening Defunding the Police stopped that dead in its tracks.

Democrats have ALL the communications majors working for them, and no damn cohesive message. Let us hope that shiny, new, all-female communications team at the White House drastically improves messaging from the top-down. Godspeed, ladies!

Love me some Dems, but yeeeeesh, the pre-election DNC message was so milquetoast, it is no small wonder that every staunch republican with a beating heart showed up at the polls. The DNC message was essentially, “Hey, Joe is not Trump,”

Dear American Thai Guy and JYStad,

I think I’ve heard this criticism before.

There are people like Barack Obama and others who believe there is power in messaging. Those people are wasting their time addressing a diversion tactic instead of addressing the problem. But just because Obama and people say it doesn’t mean it is true.

In 1918, after the NAACP started spreading the “Stop Lynching, Start Building” slogan, Rep. Leonidas Dyer introduced the 1918 Anti-Lynching Bill. According to Lyndon Johnson, Southerners objected on the grounds that Black people “were responsible for more crime, more babies born out of wedlock, more welfare and other forms of social assistance.” They rejected the bill because it criminalized law-abiding whites who felt as of “strong measures were needed to keep the Blacks under control.”

The cool thing about the text of Dyer’s bill is that it is easy to find because legislators are still trying to pass it. To this day, no anti-lynching law has ever passed both chambers of Congress.

When the civil rights movement condensed its demands into peaceful slogans such as “we demand voting rights now” or “end Jim Crow rules in our schools” or “the law of the land is our demand,” they were kicked, beaten, bitten and sprayed with fire hoses. Protesters against the war in Vietnam were vilified as anti-American for using the slogan “End the War in Vietnam.”

The reason the GOP vilified “Medicare for all” as “socialism” is not because they don’t understand the message. It’s because they don’t give a fuck about people who can’t afford healthcare. When they insisted that Obama say “radical Islamic extremism,” they didn’t think the words would magically make the Taliban vanish into thin air. They just don’t give a fuck about Muslims.

The reason America continues to oppress us and perpetuate white supremacy isn’t that we haven’t found the right phraseology. It’s because the country is littered with people who don’t give a fuck about Black people.

My point is, that the concept of “effective messaging” is a strawman used by white supremacists to ignore the goal of a movement.

But let’s suppose someone didn’t understand what the phrase “defund the police” meant. In all likelihood, that person has a device that connects to this thing called the internet. And if they went to a website called Google, literally the first result links to a page that says:

“Defund the police” means reallocating or redirecting funding away from the police department to other government agencies funded by the local municipality. That’s it. It’s that simple. Defund does not mean abolish policing. And, even some who say abolish, do not necessarily mean to do away with law enforcement altogether.

Substantively, there are many mechanisms to fight police brutality. Local officials can reduce the funding that allow local departments to militarize their forces. Federal laws can’t do much except standardize the policing and threaten to reduce the money to agencies that flout these laws. Cities can use financial means to force police unions to the table. There are studies that show that over-policing produces more resistance over time and that removing police officers can actually reduce incidents of brutality. Some people suggest that we can replace speed stops with cameras. The most ambitious people want to dismantle police departments altogether and reimagine policing with a combination of criminal investigators, traffic regulators, mental health officials and community-oriented crime-stopping.

All of these different ideas would require one thing in common: the reduction of taxpayer dollars to law enforcement agencies.

Someone should come up with a phrase for that.

I have no idea what this is about:

From: Jack R.

To: The RootWhat a racist piece of garbage Media outlet this is. Y’all should be ashamed of yourself language, shit y’all started! Here’s a hot tip Facebook needs to remove you from their newsfeed you guys are fucked up assholes! How about if I start a news media that’s all about how bad Black people are?

I think someone already beat you to starting a news outlet about how bad Black people are.

It’s called “The media.”

Finally, there was some pushback on this article:

From: Linda

To: Michael HarriotHey,

I recently discovered you and I love your writing. I want to ask you a serious question:

WHy is there

Why is racist for someone to say “colored” if the organization is called the NAACP. It’s like we spend a lot of time arguing about names and words like the n-word. If u use the er it’s racist and I can’t use it at all. But you still think it’s so important for people to say “Black Lives Matter” if they don’t want too but you get mad when I say All lives Matter?

My homeboys call me “Rickety.”

Every summer, my mother forced me to go to some summer camp or another to “broaden my horizons.” When I was about 15, I convinced two niggas from my hood, Dumbo and P, to go to the Summer Science Intensive Training Program at an HBCU, Claflin College, with me. Now P and I had been friends for years and I honestly can’t tell you how Dumbo even got involved because, before that summer, we weren’t friends.

The reason they called him Dumbo was not because he had big ears. It was because he was born with a condition called “slight macroglossia,” or a slightly enlarged tongue that for some reason caused people (teachers, strangers and even family members) to think he wasn’t intelligent.

Anyway, someone at Claflin dreamed up an idea to bring high school students to a college campus and offer them college for first-year college courses in chemistry, biology and math. It was a brilliant idea because most advanced high school courses are really low-level college courses but majority-Black high schools don’t often offer these AP-level courses. We also visited tech companies, factories and anyplace that used STEM grads.

Anyway, the cool thing about SSITP was that they actually treated us like college students. We had no curfew. We could hang out. Now, this was Orangeburg, S.C. There was no mall or really anything to do, so “hanging out” mostly meant chilling out on campus with the other students, including a Claflin student they hired as an academic tutor for our program, a senior name Joey.

Joey was a 6-foot, 5-inch basketball player from Brooklyn. He was smart, charismatic and everyone loved him. He had a couple of classes left before he graduated and he was taking them during summer school. Joey came to S.C. from N.Y. on a basketball scholarship, so he was like a fish out of water and complained about it all the time. When Joey met my friends, who were just some hood niggas I had convinced to leave the neighborhood for the summer, he latched on to them immediately. Perhaps it was the shared ghetto sensibilities.

Because Joey was so charismatic, by the end of the summer, Bo and P had picked up N.Y. accents and had started calling me by the nickname Joey bestowed upon me the first time he saw me: “Rickety,” because he said I had big lips like the cartoon car in Rickety Rocket.

Bo thought college (and all school, really) was useless, and I understood why. Because people associated his intelligence with his speech, Bo, who was what we call “nice with his hands,” became a street nigga at an early age. P planned on going into the military after high school and Bo had a job waiting on him at a local factory. They had no business taking these advanced courses, but I convinced them that the shit wasn’t that hard. Honestly, I was lying but, what’s the worst that could happen? They actually hung in there, attended classes and—with some help from Joey—Bo and P actually passed the courses!

When we went back to our hometown, these niggas continued to call me “Rickety.” Then my other friends started calling me “Rickety.” When my friends came over to my mom’s house, they’d ask for Rickety and she’d know who they were talking about. To this day, if you are from my hometown, you probably know me as Rickety, even though Bo and P don’t live there anymore

Where’d they go?

Well, the next year, our senior year in high school, P died in a drunk driving accident.

That shit wrecked Bo. Bo had known P all his life and, until that summer, P was the only person who even treated Bo as if he was not a Dumbo. He never asked me to do it, but after that summer, P and I just basically evolved into calling him “Bo,” all the time. Joey even came to P’s funeral. He had found a job working at a pharmaceutical company in Virginia and told Bo that he might be able to get him an entry-level job but he’d have to pass the company’s entrance test.

The same day, Bo dropped out of high school; relocated to Virginia; moved into a one-bedroom apartment with Joey and started studying to pass the test. Apparently, when he applied for the job, Bo didn’t even have to prove he had a high school diploma because they had college credits.

Joey eventually took another job but Bo worked there for years, married and raised a family. After a few years, the job even gave him the opportunity to attend college. I called Bo the other day, and we started talking about that summer. I asked him: “I wonder what happened to Joey?” and he casually replied: “Oh he works here. “I hired him a couple of years ago...He asked about you. Do people still call you Rickety?”

I told him that no one outside of my hometown knew what it meant, to which he replied that he didn’t either, and then it hit me.

In our hometown, we had two and a half television channels. No one had ever seen Rickety Rocket. I had only seen it spending summers with my aunt in N.J. Literally, no one who called me that nickname had ever known what it meant.

Now, during that phone call, I didn’t ask Bo if people still used his nickname because I remember, on the way to Claflin that summer, while P’s mother was driving, Bo said to us: “Hey, when we get there, just call me Bo.”

At P’s funeral, Bo had to stop Joey from kicking someone’s ass for calling him “Dumbo.”

My point Linda, is this:

Speaking someone’s name is a metaphor for how you relate to the world. Most people blindly, without thought, accept what others have named things without thinking about it. What I fail to understand is why it’s so hard for people to treat people with kindness and respect when they know their actions are hurtful to others.

So I reject your question, Linda. Instead, I ask you this:

Why do you want to hurt people?

Why is it so hard for so many white people to change their actions—especially actions they have never even thought about—for the sake of being a kind human being. Is white privilege that hard of a shell for you to remove? Why are you so insistent on being mean when being nice won’t hurt you a tiny bit?

I honestly believe Bo didn’t escape our hometown because of our friend or his unstable future. I believe he was escaping the thing that named him. I think that’s why he left our hometown and moved in with Joey. Joey was probably the only person who didn’t treat him like Dumbo. And like “Rickety,” most people didn’t know the origin of Dumbo’s name. I believe people wouldn’t have called him that if they knew it bothered him because most people aren’t assholes.

Most people.

But Joey probably doesn’t call Bo “Bo” anymore.

He probably calls him “Dr. Bo”...

These days, Dumbo is probably one of the rare, if not the only person in America who has a Ph.D. but not a high school diploma.

He still calls me Rickety.