If you had to pick between the ability to fly or the ability to become invisible, which would you choose?

This infamous conundrum is actually a psychological test that reveals deep-seated personality traits. The decision supposedly represents the subconscious choice between becoming the person you want to be or hiding the person you truly are. And for most of our lives, we have been led to believe that by 2020 we’d have battery-powered jetpacks readily available in the local Walmart that gave us the ability to zip through the air and fulfill our fantasies of flight.

The other choice was only hypothetical. Although many of us would love to hear what others say about us or see how they behave when we are not around, only in our wildest dreams could we imagine that we could cloak ourselves in the anonymity of invisibility. Until now.

There’s an app for that.

In the past few years, social media companies and the tech industry have created a cottage industry of miniaturized social networks that allow users to anonymously connect with people who share the same interests, backgrounds and—in many cases—location. Although avatars and screen names allow for the illusion of familiarity, neighborhood apps like Nextdoor and Neighbors allow people who live in the same vicinity to anonymously communicate with each other about their street, block or subdivision. With this new technology, people who live near each other don’t have to actually know each other to share information about missing dogs, broken streetlights or crime.

And racism.

A lot of racism.

Describing itself as ”the world’s largest social network for the neighborhood,” Nextdoor is by far the most popular of these apps. Potential members who own or rent a home in a neighborhood can sign up for the service and, after a verification process, become part of a small network that “enables truly local conversations that empower neighbors to build stronger and safer communities,” the website explains.

Numerous media outlets have published stories about how Nextdoor fuels incidents of racial profiling and bigotry. The app has been called everything from “a home for racial profiling” to “Twitter for old people.” The company has proactively tried to address these concerns by tweaking its algorithm and informing its users about implicit bias.

But Nextdoor has also had a profound effect on those who are not racist but were astounded by the sheer prevalence of casual racism practiced by people around them. When The Root asked Nextdoor users about incidents of bigotry on the app, many users—both black and white—explained how becoming a virtual fly on Nextdoor’s virtual walls changed their perception of their neighbors, friends and racism in society as a whole.

“I downloaded the app for my parent’s beach house in Bethany Beach [Delaware],” explained Cameron Childs, a 24-year-old white man from Virginia. “My parents moved to Florida so the only people who use the house is me or my sister. If you’ve ever been to Bethany Beach, its small and pretty white. We basically know everyone in the neighborhood since we were kids.”

Childs recently married an African American woman who had a child from a previous relationship. He still receives his parents’ email alerts from Nextdoor posts, to check on the weather, storm damage and break-ins for the vacation home and is often shocked by racist posts by people he’s known for years. But there was one particular post that really upset him.

“My wife took our daughter to the beach house and I was going to meet them there the next day,” explained Childs. “As soon as they arrived, before they could put the key in the door, someone had called the police on a ‘suspicious woman’ trying to break into the house… with a key!”

According to Childs, his wife didn’t even have the chance to tell him about the police encounter. She just explained the situation to the cops and they left. He read the details of the incident from people who were discussing it on the Nextdoor app. When he received the alert, he recognized the familiar phrase used by his neighbors when black people are spotted in the vicinity:

They call it a “Spook Alert.”

“My wife took it with a grain of salt but it really opened my eyes,” said Childs. “I saw their racist things every day but it never bothered me until it affected me. In my head, these people weren’t angry racists. These were my childhood friends. They were like family to me. They were… they were just like me.”

“My new neighbors are more racist than I thought or expected,” said Cass Riddick, a black D.C. resident who says working for a neighborhood commissioner means she has to read residents’darkest posts. “[Nextdoor] is filled with some of the most racist and crazy individuals who have gentrified D.C. and it is laughable at what they post.”

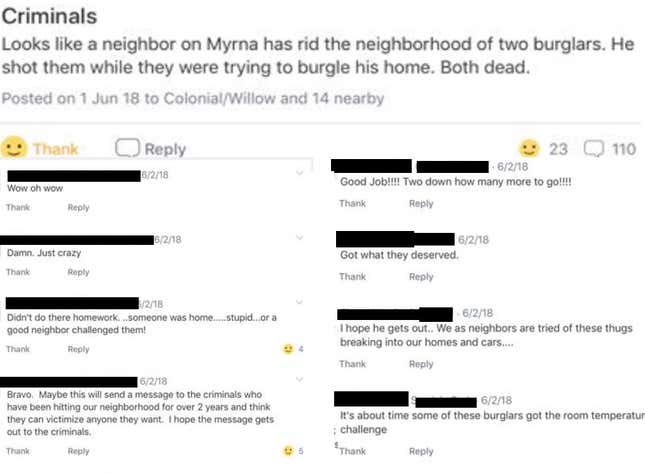

Mary Jo Harmon forwarded screenshots to The Root of a Nextdoor exchange where her neighbors celebrated a homeowner who shot and killed two alleged burglars (one of whom was reportedly 17 years old) who neighbors described as a “thug” and “animals.”

“I was working on a research project during the time this occurred, looking at children involved with the courts to assess their levels of trauma,” said Harmon, who—instead of going off— shared statistics, quotes, and research with her neighbors to try to get them to see that they were overwrought about crime and violence in their area, to no avail. “This exchange wrecked me.”

“I grew up in liberal New York City and Nextdoor exposed me to racism,” recounted Rebecca Stinton, a teacher in the suburbs of Madison, Wis. “I now live in a conservative, white subdivision and I literally know every time a black person comes in the neighborhood. It makes me so angry to see so much casual racism that I deleted the app. I imagine it’s like that everywhere.”

And then there’s this story, told to The Root by former Nextdoor member Ian Aiello:

I often walk to and from work. One night, around 3:30 am, I leave and walk home. I didn’t notice anything weird. The next morning my partner tells me to check my phone. Someone described me to a t, and said I was a “dark, suspicious man checking car doors to see if they’re locked.” Someone else mentioned I was Hispanic or “darker” and they’ve seen me casing houses. Finally, another person said he grabbed his gun and drove around looking for me and other neighbors cheered him on.

I’m mixed race (Japanese/ White) but am pretty ambiguously ethnic. I’m confused for Puerto Rican on the east coast (where I’m from) and blanket Hispanic here in Nebraska. It’s whatever.

I got on and told them it was me, a neighbor, and that I’m active in the neighborhood cleanup and that it’s pretty messed up that I walk there almost every single night. I walk my kids around every day and specifically asked the guy with the gun what he planned to do with it. I was told I shouldn’t walk after dark and I shouldn’t wear my hoodie if I don’t want to seem suspicious. I was pissed off but my partner convinced me to let it go.

Flash forward a few months. A transgender individual was walking through the neighborhood in the evening and got picked up on a Ring doorbell. Members of the neighborhood began mocking this person. Neighborhood Leads (sort of a moderator) began calling them “trannies” and made memes about their appearance and posted them.

I went scorched earth and told them off. They began saying I was the individual walking and that it’s not a great disguise to break into cars with. They used all sorts of slang for homosexuals and Hispanics and one person posted a screen shot of my Facebook page with my children on it. I logged off for the night.

The next day I tried to log in and found myself banned. I know for a fact that none of the individuals who were involved were banned, only me. No email warnings, no pop-ups advising my behavior was uncalled for. Just unable to log in.

I mean, yeah I’m in Nebraska, but it was a gross display that the company backed up by banning only me. I don’t want back in either.

Fuck that site.

None of the people who complained about Nextdoor blamed the app for the racism they experienced. And many others acknowledged a few negative incidents but still found the app tolerable.

“Not specifically racism...but you know how things are coded. ‘Dark-skinned man knocking on doors,’ ‘young thugs riding around neighborhoods looking at cars’”, explained one Charlotte, N.C., Nextdoor user. “I will say that there is not a ton of it where I live, because my neighborhood is very blended. But there was a rash of break-ins a few years ago (mine included) and the older [white women] on the app let it be known to be on the lookout for those thugs.”

Still, the Nextdoor stories range from the ridiculous to the sublime.

Neither Nextdoor nor Neighbors have responded to The Root’s request for comment. Ultimately, Nextdoor is just a piece of technology and a tool for communication that can be used for good or evil. These apps aren’t creating more discrimination. When someone burns a cross or sends a racist letter, it is not the fault of the tree that produced the paper or lumber.

“I mean, there’s racist people on Facebook, on Twitter, everywhere,” said Stinton. “It is like being a fly on the wall in a roomful of racists who all think they are invisible. I can’t imagine what it’s like for a person of color to have to see that.”

“I can,” said the invisible black man.

“It’s like living in America.”