“You are my worst fear realized,” a black woman—and complete stranger—said to me after I concluded my keynote speech. She continued, “I came to hear you speak, and you have confirmed my worst fears. You aren’t a true black person.”

I am part of the first wave of transracial adoptees (I’m black, my parents are white) who grew up in a closed and secret adoption (I had no contact with my biological parents, nor did they know where I was). I was invited to speak at a national adoption conference to share how finally meeting my biological family helped me weave my racial identity together. Prior to taking the stage, I’d engaged in small talk with this same woman, completely unaware that I was speaking to a former member of the National Association of Black Social Workers, and one of the authors of a scathing rebuke (pdf) of transracial adoption. This was a woman who “…stands against the placement of black children in white homes for any reason...a white home is not a suitable placement...”

Donning my brightest smile, I stood confidently on stage and shared the beginnings of my life. I was abandoned at a Tennessee hospital, nameless and with a diagnosis of “failure to thrive.” After a few days, I was moved to my first foster home, where I remained for a year while social workers searched specifically for black parents to adopt me. But no one came. Instead, I was adopted by a white couple in Washington state. I didn’t see my birth family or my community of origin for 26 years.

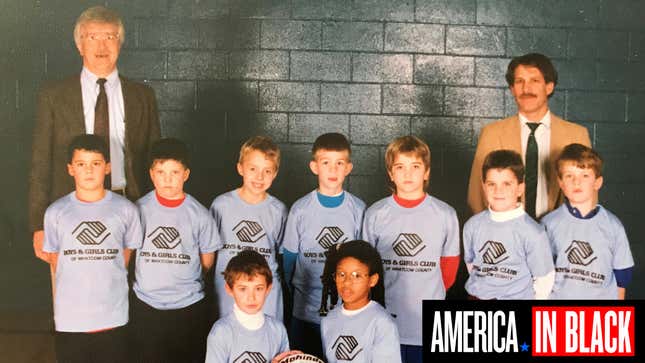

My white parents were politically conscious, devoted to inclusivity, and committed to using their privilege for good. As a child, my mom called out Johnson & Johnson on their “nude” bandages, asking them to create clear Band-Aids so brown-skinned people could inconspicuously use them, too. When the white citizens of our town showered stereotypes upon me because of my natural athleticism, “fast-twitch” muscle and exotic look, my dad countered their assumptions by pointing out my ability to play classical piano, my love for reading and gave a primer on the historical objectification of black bodies. By all accounts, I grew up in a loving, education-centric, anti-racist and privileged home.

However, growing up in a closed adoption and in a former “sundown town” meant that I wasn’t able to participate in the black community. Not knowing my birth family meant that I would fantasize often about each of them. I dreamt that my birth mother shared my love of fashion and that my birth father was Magic Johnson, because his large smile and love for basketball mirrored two of my own traits. Being transracially adopted echoed the stereotype that black parents were unfit to parent and that black folks still needed rescuing by white people. I came to embrace white societal standards and became a de facto operant of white supremacy.

As a child, and throughout my teen years, I made friends easily and enjoyed the activities of my daily life, yet routinely served as a living prop to cement someone else’s racial awareness. I was keenly aware that I did not quite belong. Because to belong meant that I could find products for my coarse afro-textured hair at a local store, makeup would be available in my skin color and I wouldn’t be petted on a weekly basis by curious citizens who wondered what my hair felt like. To belong meant I’d need to be white.

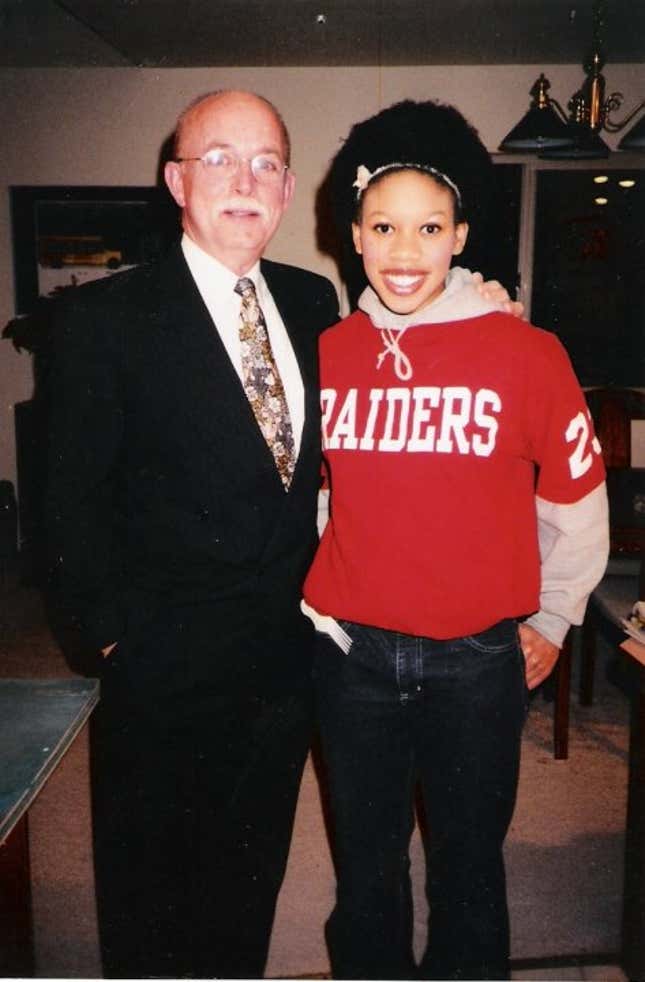

It wasn’t until I was 26 years old that my adoptive family and I found my birth family through the miracle of Facebook sleuthing. Upon reuniting, we learned that my birth mother had wondered where I went every single day of her life. Her steadfast prayer for me was that I was with a family that provided me with lots of opportunities in life. Having begun a relationship with my biological family, I now straddle two worlds, both racially and socioeconomically.

Armed with a decadelong career in child welfare, I have been on the frontlines witnessing child removals by less than qualified workers, legal adoption proceedings providing false information and court hearings terminating parental rights because the biological parents couldn’t get their children to school on time. I found that problems within wealthy white homes are viewed as a private matter, whereas problems in black families get catapulted into the public child welfare system. I routinely cite the very statement that this woman helped to pen in order to ensure that families understood that the NABSW was not stating that white people couldn’t adequately parent black children, but instead, they were attempting a strategic effort to stop the systematic dismantling of black communities by any means necessary. In the early 1970s, Jim Crow laws had barely died, the crack epidemic led to the mass incarceration of black bodies and Patrick Moynihan was talking about the “disorganized single mothers in the ghettos.” Black communities were being torn apart and the child welfare system had become yet another institutional arm used to weaken the black family structure.

The NABSW’s charge of racial genocide may be alarmist, however informal adoption and support from extended family networks have long been an integral part of our survival and as such, black families have become quite adept at providing flexible support to protect their families when facing social and economic adversity. Black people have cared for other people’s kin since the 17th century. However, around the 1960s, white people began adopting black children through the formal child welfare system. Perhaps even more alarming is the allowance of well-intentioned, anti-racist, loving white parents to believe that their individual act of adopting a child of color is separate than the systemic belief that black children must be saved from the social ills of their culture.

Never breaking eye contact, the black woman continued; “I’m sorry the system erased you from our culture.” Her body language communicated defeat. I imagined that she had poured much of her career into preserving black families, and hearing my story was a giant slap in the face. I can only guess, though, because after uttering a few more harsh words, she was gone. Although black culture is not a monolith, I wonder if black transracial adoptees need an asterisk behind our racial identity. To this woman, black transracial adoptees are racial imposters.