ALBANY, N.Y.—TS Candii stepped outside of her apartment complex in the Bronx last summer and was immediately stopped by an officer from the NYPD. First, he accused her of being a sex worker, a profession she has participated in, but not on that day, Barbii told The Root. Then he asked her to become a confidential informant, to rat out drug dealers in the neighborhood, offering her $1,500 to agree. She didn’t. And that’s when the situation escalated.

Candii understood well what was happening. She had been stopped by New York City police at least twice before that day for “being a black trans woman,” she said.

The cop threatened to take her into custody and charge her with prostitution—even though her only crime seemed to be daring to leave her apartment—unless she performed oral sex on him, Barbii said.

Feeling as though she had no choice and worried for her safety, she complied, and the officer let her go.

“Every time I’m walking outside, I feel like I’m profiled for prostitution because I am a transgender woman,” Candii said inside of a McDonald’s inside of the state capitol in Albany, N.Y., on Tuesday morning. “I honestly feel like I’m a criminal. I feel like my existence is illegal in the state of New York.”

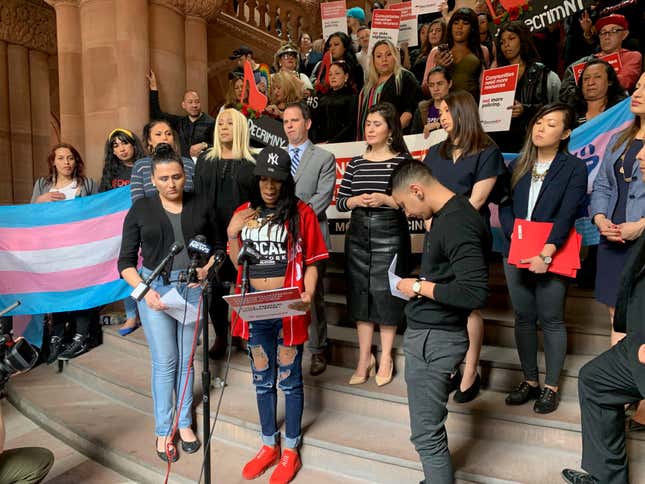

Candii’s story is similar to those of the more than 100 current and former sex workers from New York City who went to Albany to advocate for two pieces of legislation they say would protect them from abusive policing. Currently, a 1976 New York state law allows police officers to arrest people for loitering for the purpose of prostitution, even though “purpose” is not clearly defined. Several assembly members and senators wrote a letter to the NYPD inspector general last month questioning the wisdom of policing sex trafficking alongside sex work between consenting adults. As of now, sex work is illegal in New York state and virtually everywhere else in the union.

Candii and other women The Root spoke to are part of the organization Decrim NY, which is pushing for full decriminalization of sex work in the state. Current laws allow for too much space for abuse by police officers, who can take advantage of people taken into custody on prostitution charges, activists say. That abuse includes sexual assault and being forced to become a CI. That’s why activists arrived at the state Capitol after 9 a.m. Tuesday, hoping to convince lawmakers to back the legislation before the annual legislative session ends next month.

One of the bills, S02253/A00654, would lead to the repeal of the loitering for the purposes of prostitution statute. Known as the “Walking While Trans” ban, the statute lets police arrest people based on their appearance, or if they are suspected of trying to trade sex for money—even though what constitutes suspicion is not well defined and has been unevenly applied. Between 2012 and 2015, more than 85 percent of the people arrested in New York City under the statute were black and Latinx women.

The other bill, S04981/A06983, allows for trafficking survivors to have their records cleared of any charges levied in connection to what traffickers forced them to do. But New York only allows trafficking survivors to clear prostitution-related records, not the drug and trespass-related ones that also stem from the trafficking they had to survive. Neither bill is scheduled for a vote, and there is a strong chance lawmakers will not get to them before the annual session ends.

Activists have spent the bulk of their time and lobbying efforts educating lawmakers on what sex work is and how different it is from sex trafficking, a distinction that often gets lost in such debates. They also made clear that the bills they are pushing would still let law enforcement go after traffickers.

Jared Trujillo, a lawyer advocating for Decrim NY who was at the capitol yesterday, said some of the black and Latinx lawmakers he spoke with come from areas where the highest rates of arrest of trans women of color take place. They support the bills but fear push back from conservative community leaders who, frankly, don’t approve of people selling sex. The lawmakers told him once they publicly support the bills, they would need him and other activists to come to their communities and educate leery constituents who fear the bills will give sex traffickers a free pass.

“This is going to require a bit more community education than we initially thought,” Trujillo said after his meeting with legislators. “I still do firmly believe in people hearing human stories; how they hear about people being policed and how full decriminalization will elevate people and make a tangible difference in people’s lives.”

One of the most vocal supporters of the two bills is state Assembly Member Catalina Cruz from Queens. She’s confident the bills will pass eventually, but follow-up legislation that will take sex work off the penal code completely will get people up in arms, she said. Sex workers are viewed as needing to be saved because their work is viewed purely from the lens of force, not choice, Cruz said. Her husband, a police officer, who shares the aforementioned mindset, is one of the people whose mind she is working to change.

“You don’t get to decide whether someone wants to do this or not,” Cruz said. “If and when you find out they are doing it by force, you can do what you need to do. But if they are doing this because they want to, who are we or who are you as law enforcement to say otherwise?”

Cruz said activists visiting the capital is crucial because lawmakers will have a face to associate with people who have been abused by police, as well as penal codes that have harmed sex workers. Early in her career, Cruz was not a supporter of sex decriminalization—until she heard trans women of color share their experiences with law enforcement.

State Sen. Ron Kim was not an advocate of decriminalization until he heard the tragic story of Yang Song, who fell four stories to her death in 2017 while fleeing arrest during an NYPD Vice sting operation. But he now supports the two bills. Besides removing the stigma of sex work, decriminalization can eventually become an economic booster for local communities, he said.

“Sex work is the truest peer-to-peer economy we have that retains money in our neighborhoods,” Kim said. “Everything we are doing is extracting the dollars out of our communities. We’re rewarding the biggest, baddest corporations, and we’re crushing the mom and pops.”

On the bus back to New York City, I spoke with Audrey Melendez, a black trans woman and former sex worker, who said she was put off after her meeting with a white staffer who sat in place of his lawmaker. The staffer told her he, too, was marginalized by society as a gay man. He didn’t seem to understand her hyper marginalization as a trans black woman, Melendez said. Just three months ago, before she got her current job, Melendez was trading sex for money, which she feels she has the right to do if both parties consent. But even though she is no longer a sex worker, police still harass her because of how she looks or what she is wearing, she said.

Melendez admitted she was worn out emotionally, worrying that lawmakers do not appreciate how repressive her life is as a black trans woman in New York City. Everyday she steps foot on the street, she is subject to arrest or police abuse. By taking the right legislative steps to decriminalize sex work, Melendez and other marginalized LGBTQ people say they will have fewer fears walking the streets of New York City.

“I’m here speaking not only for myself, but for thousands of my sisters who unfortunately have to do this on a day-to-day basis to survive and pay their bills,” she said. “They can’t be here because they have to be home everyday, every hour on the hour, because every client counts. They don’t have a day to come to Albany and to speak on their issues.”