Pastor Rahsaan Armand knows the devil exists.

But as he sped through the rural roads near West Virginia’s Marion County-Monongalia County line, he had no idea he was headed in the devil’s direction. Armand didn’t even know where he was going.

Armand had already officiated the morning service for his congregation at Mt. Zion Missionary Baptist Church in neighboring Clarksburg, West Virginia. He was rushing to preach at Rev. Laverna Horton’s sixth-anniversary service at Friendship Baptist Church in Everettville on March 15. Armand’s wife, three daughters and 10 of his congregants left before he did and had already squeezed into Friendship’s crowded sanctuary for one of the most important traditions in his religious community.

“In the black Baptist church, there are two high celebrations,” Armand told The Root. “The first is the church anniversary and the second is the pastor’s anniversary...So you had churches from the tri-counties converge on her church to pat her on the back, to celebrate her, to eat with her...It’s what we do. It’s just what we do in the black church.”

Aside from being lost, at that point, Pastor Armand had no idea that asymptomatic carriers could still spread the coronavirus. West Virginia Gov. Jim Justice had not yet issued a stay-at-home order. In fact, as the pastor crept through the West Virginia countryside and the coronavirus crisscrossed the country, the state would not report a single case of the virus for another two weeks.

All he knew was that he was late.

Armand did not make it in time to Friendship Baptist to preach the service. As he pulled into the church’s overcrowded parking lot, he observed 100 to 120 worshipers trickle out of a cramped building that was meant to hold 75, at best. He greeted his church members who attended the service. He watched as members from Morning Star Baptist—of one of the region’s biggest black congregations—helped the elderly woman affectionately known as Sister Horton climb into Morning Star Baptist’s church van. Sister Horton never missed an afternoon service and, even though she was one of the oldest members in attendance, she still sang on the choir.

Two weeks later, on March 29, 88-year-old Viola York Horton would become the first West Virginian to die from COVID-19.

Less than 24 hours after that fateful church service, Gov. Justice would issue a proclamation restricting gatherings of more than 10 or more people. But on March 15, as Sister Horton sang her last hymn, no one had a clue that a virus, which attendees would repeatedly refer to as “the devil himself,” was also spreading its gospel. Because testing was so scarce, Horton’s family wouldn’t know for days that this cruel contagion caused her demise. Pastor Armand was not aware that one of his congregants would soon test positive. He did not know that a microscopic deliverer of death was preparing to tear through his community like an unleashed demon.

“Had I known there was even the possibility of a single person becoming infected, I definitely would have refrained from going and would have advised my congregants to not be in attendance,” Armand said. “We knew that something was brewing, but at that time, West Virginia was not reporting any cases. We haven’t heard anything from the governor.

“So we are looking as the rest of the country is covered in red and we’re still in white, wondering,” Armand added. “We were wondering: Has God done something to protect West Virginia?”

He did not know.

Almost Hell

John Denver called West Virginia “almost heaven,” a phrase that sparked an award-winning campaign for the state’s tourism council.

While West Virginians believed their pastoral existence protected them from the then-burgeoning global pandemic that hit more urban areas, their state still has the fourth-highest poverty rate, the second-lowest life expectancy and the highest drug overdose rate in America. The state also ranks among the worst 20 states for teen birth rates (45th), violent crime (31st) and education (44th). However, with all its problems, the state actually has one redeeming, top 10 attribute:

White people.

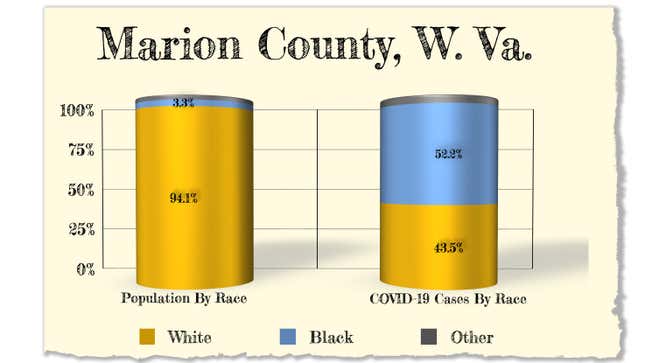

West Virginia’s 92.0 percent white population makes it the third-whitest state in the country. Marion County is even whiter. Tucked into the northern part of the Mountain State, the rural county is 92.9 percent white. Still, Marion County’s tiny black population is close-knit and deeply religious, often uniting to worship together at one of the area’s black churches for Sunday afternoon services.

The state has also managed to escape the coronavirus epidemic that has been ravaging America. It has tested a larger percentage of its citizens than 37 other states and, luckily, it has one of the lowest infection rates in the nation.

Unless you’re black.

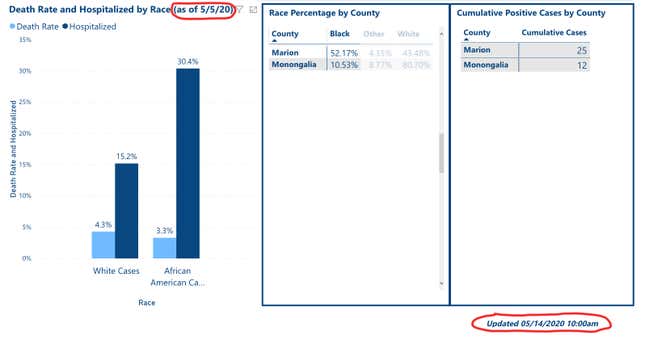

If you’re black in West Virginia, you’re twice as likely to test positive for the coronavirus. And, as of Monday, May 5, data from the West Virginia Bureau for Public Health, 52.17 percent of Marion County residents who have tested positive for COVID-19 were black; an astounding number, considering that the county is only 3.3 percent black.

Those numbers are not right.

The Root has reviewed mounds of emails, read dozens of letters and conducted interviews with residents who live in Marion County and the surrounding area. The number of black people infected in the area is unquestionably higher. Furthermore, health officials, activists, politicians all told The Root that nearly every single case of COVID-19 in Marion and Monongalia Counties’ black population can be traced back to that jam-packed March 15 service at Friendship Baptist Church, a fact backed up by state and county data.

COVID-19 is tearing through Marion County at an appalling rate. Even worse, state and county health officials seemingly ignored a disastrous public health crisis; the victims were left to fight this pandemic on their own—until a handful of fearless first responders stepped in to save this small black community.

No, the saviors were not doctors or nurses. In fact, none of them had any healthcare expertise. They were the other kind of “essential” workers who are used to being on the front lines:

Of course, it was black women who saved the day.

Romelia Hodges had to know.

Hodges, a community activist in Fairmont, W.V., (the county seat of Marion County), was watching the COVID-19 pandemic from the beginning. One of the reasons she was so adamant about protecting her community was because of a rare immunodeficiency called Volga anemia, a blood disorder common in the Volga River region of Russia. The illness is so rare in the U.S. that about a dozen people in the entire country suffer from the illness.

Three of them live in Romelia Hodges’ home.

Experts from the Mayo Clinic, Johns Hopkins and other institutions diagnosed Hodges’ husband, Patrick, with the uncommon disorder years ago, when a mystery illness landed him on life support at 25 years old. After unraveling the medical mystery, researchers informed the couple that Volga anemia was genetic and had been passed to their two sons.

Knowing that a bout with the coronavirus could prove deadly to her family, Hodges had been watching the COVID-19 pandemic unfold with a particularly personal interest. She had stocked her home with oxygen, homeopathic remedies and disinfectant.

And she prayed.

“I’m thinking, my God, if I have to take this man into the hospital with respiratory distress, I am never going to see him again,” Hodges told The Root, thinking of her husband’s immunodeficiency. “He knew this and I knew this.”

Hodges attended the March 15 service with her 10-year-old daughter, who performed with a liturgical dance troupe at the service. Hodges was aware that the coronavirus was ravaging the country but assumed it had not yet reached the part of the country where she lived.

“West Virginia, at that point in time, was in a false sense of reality. That’s what I like to call it because we didn’t have any cases,” Hodges explained. “Our governor and President Trump were kind of touting that. But we were in a false sense of reality because the reason that we didn’t have any cases was because we only had 150 tests in the whole state, and they weren’t doing any testing...They were making it very, very difficult to test.

“It was a beautiful, beautiful pastor’s anniversary, one of the most blessed that I’ve been at, to be honest with you,” Hodges noted. “And the interesting thing about this is this is a tiny church. This is one of—if it’s not the—smallest churches in our region. I would almost bet on it.”

Among one of Hodges’ many community activities was running a private Facebook page called Fairmont Alliance of Minorities (FAM), dedicated to erasing the disparities among Marion County’s black residents. By March 20, Hodges began to notice that friends, neighbors and fellow churchgoers were starting to exhibit COVID-19 symptoms and decided to alert the community of a possible community spread.

On the same day, Hodges placed a call to Marion County Health Director Lloyd Wright. Wright, who did not respond to The Root’s requests for an interview, offered no assistance, Hodges said. Meanwhile, other Marion County residents who attended the Sunday service were being turned away by the county health department, which arranges testing. Despite informing health officials that they were at the scene of a possible community spread, healthcare workers told them that they needed to show symptoms to get tested. How could this be state policy if officials knew that asymptomatic people could be COVID-19 carriers?

The Root has reviewed multiple emails from state and local officials revealing that, at the time, there were only enough supplies for 150 COVID-19 tests for the entire state of West Virginia. The day after the pastor’s anniversary celebration, Hodges watched the press conference where Gov. Justice told citizens that he was assured by President Donald Trump that any West Virginian who wanted to get tested could get tested for free. Hodges would later watch state health authorities dispatch the National Guard and set up mobile testing centers for nursing home residents after the governor proclaimed the elderly to be a “vulnerable population.”

“I called Lloyd again a week later,” said Hodges. “I told him, ‘More and more people are getting sick. How many people do you need to be hospitalized before you come in like you did the nursing home and Morgantown, West Virginia, and bring the National Guard and test our community? You know we are being disproportionately affected here and we’re not getting the resources and services that we deserve.’ He hemmed and hawed. He said, ‘You know, we would have to send them out the survey. They have to meet the CDC requirements to be tested,’ this and that.”

Undeterred, Hodges essentially assembled her own all-star team of black women to stop the pandemic all on their own. With no official help from local authorities, they used the one resource that never fails:

The hookup.

The hookup is legendary in the black community. Barack Obama called it “community organizing.” It’s how Harriet Tubman freed the slaves. In fact, the Underground Railroad was essentially a multi-state system of interconnected hookups.

Hodges and her team of black female saviors may not have been able to wield any power but they had the hookup. The team included:

- Del. Danielle Walker: Who represents neighboring Monongalia County in West Virginia’s House of Delegates

- Tiffany Samuels: A development director for the West Virginia University Cancer Institute, which just happens to also employ Dr. Clay Marsh, the designated “COVID Czar” for the tri-county region.

- Terry Berkley: Who happens to work in the office of Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W. Va.)

The group reached out to the deacons and pastors of all the churches who attended the March 15 service. The alliance of ministers went back to their congregants and began spreading the word. The women (again, with no healthcare expertise) taught themselves how to do contact tracing.

“I just researched what they were doing in Cleveland, New York and D.C.” Hodges told The Root. “The tri-county region public health officials have an app that people can use to assist them in social tracing. They had it the entire time and never made us aware of it. Danielle [Walker] found out about it when she met with delegates.”

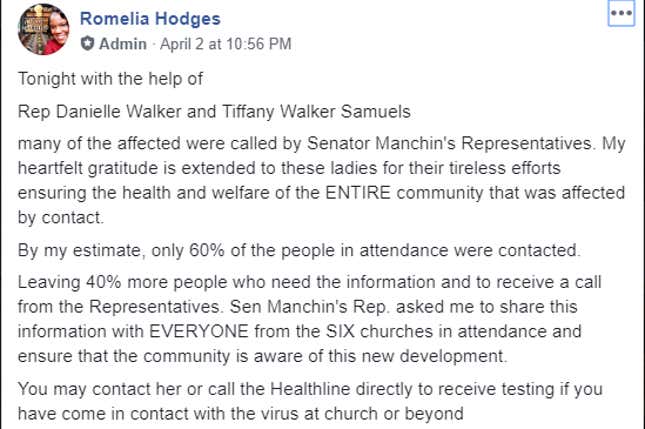

When they completed their detective work, the group had compiled a list of 89 people who may have been exposed to the coronavirus. The group’s next step was to put a full-court press on state delegates, the COVID czar and local health administrators. By April 2, telephones started ringing in black households all over Marion County.

Sen. Joe Manchin had arranged free testing for every single person on the list.

So, as more positive test results came in from Marion County’s black population, the state finally took action: They just stopped counting.

The state continues to report the total infections, but three days after Manchin’s office secured testing for black residents in the tri-county area, the Bureau of Public Health discontinued its practice of sharing COVID-19's racial statistics. Curiously, as of May 13, the West Virginia Department of Health and Human Service’s COVID-19 site still lists Marion County and neighboring Monongalia County with 36 cases among black residents, which doesn’t seem strange, except for one fact:

At least 42 individuals on the original list compiled by Hodges’ group, all of whom are black, have tested positive.

When one combines the number of Marion County’s reported positive cases with neighboring counties, the state’s racially disaggregated data still does not reflect the true black infection rate.

See? Problem solved.

“I’m still trying to fight for our right to know,” Del. Walker explained. “We need accessibility, testing and for black and brown people to be included in the vulnerable population. In West Virginia, the only group that they look at as being a ‘vulnerable population’ is the elders. And I still don’t even know how many of the elders or people in the black and brown community are affected and that’s not fair.”

Samuels continues her advocacy from the inside, connecting the community with people in the healthcare industry. She also assists area residents with transportation and access to care. Samuels is intimately familiar with the lack of access to medical care for one specific reason. On March 17, two days after the pastor’s anniversary, California-based Alecto, one of the region’s largest healthcare providers, made an announcement that—in the midst of a global pandemic—stunned Marion County residents, both black and white.

It was closing the Fairmont Regional Medical Center—the only hospital in the area.

“We need more testing and more targeted testing,” Samuels explained. “Just yesterday, we assisted a gentleman whose brother passed away from COVID-19, and he was turned away from the testing facility. He told them that his brother passed away and that he took care of his brother and he does not feel well and they still turn him away. I don’t understand it.”

None of the churches in attendance have held in-person services since the March 15 gathering. He continues to lead the ministers’ alliance, which has created community-based goals that extend beyond healthcare and has moved his worship services online.

“The Bible says: “For lack of knowledge, my people perish,” Armand recounted. We were disseminating the knowledge as we received it from on high—the government, the CDC, the experts, the epidemiologists—we were giving it [COVID-19] to our community. And without these women being on the case, I don’t see how many more would not be affected. I don’t see how many more might not even, I dare say, be dead.”

For their work, Hodges, Samuels, Walker and Armand were appointed as a commissioners on the newly created COVID-19 Advisory Commission on African American Disparities by the state’s Department of Health and Human Resources. Finally through with the state’s disastrous response to the outbreak, Hodges could relax and take care of her family.

And finally, Hodges knew her family was safe. It was nearly 20 days after the church service, and she had quarantined the entire family since the gathering, so she decided to celebrate her team’s accomplishments by taking a relaxing shower with her new haul of scented products from Bath & Body Works. When Hodges exited the shower, her husband Patrick knew something was wrong by the look on his wife’s face.

“I get out the shower, dripping wet,” Hodges recounted. “I go over to the bedroom and I say to my husband as I squeezed the bottle at him: ‘Can you smell this?’And he said, “No. But I can smell you! What, what is your problem?”

“So I come down to my desk...and I pull out a bleach wipe,” Hodges continues. “I have industrial bleach wipes that they use in the hospital and I go to clean off my keyboard and my mouse. As soon as I open the bottle, [I can usually] smell the bleach that comes out of it. So I say to my husband: “I can’t smell this bleach bottle.”

While researching the coronavirus earlier, Hodges had already stumbled across an article about Utah Jazz player Rudy Gobert, who lost his sense of taste and smell during his battle with COVID-19. She recalled all the times that her husband and sons had fallen ill. She looked at the oxygen tanks they had stored around the house for the illness. She knew there was no hospital in the area. But, after a lifetime of tomboy activities, she was diagnosed with seasonal allergies when she was 40 years old. She prayed that it was allergies and not the coronavirus that made her lose her sense of smell.

Then she started feeling congested. Then she broke out in the little-known “COVID rash.” Then it hit her youngest son. Her oldest son started feeling symptoms, too.

Then, it hit her husband.

Hodge’s story was not over. The devil had come knocking...

Again.

Through all of the rigamarole with the Marion County Health Department, politicians and health facilities, 18 days after the portentous Friendship Baptist service, Hodges had not yet been tested. Even though her situation may have been the most precarious of all the parishioners at that service, she was determined not to use one of the precious, limited number of available tests on herself. Now she was infected with the disease, while still caring for her sick husband and sons.

As Sen. Manchin connected the group of possibly infected worshippers and their families to a testing site, Hodges arranged for transportation for an elderly woman, loaded her husband into the car and went to a separate facility even further away because his immune systems were so compromised.

She still didn’t stop.

Hodges was on a conference call with Armand and the ministers’ alliance and local health officials when she received a call informing her that both she and her husband had tested positive for the coronavirus

“I was shocked,” Hodges explained. “From all indications, even from the CDC, by 14 days, you should be over this thing. So being 20 days out and still being positive and I hadn’t been in contact with anyone else. And by that time, my husband was already severely ill. I knew that there was something very awry about what they were telling us.”

By now, the list of people exposed had grown to 107 people. Luckily, her hookup team’s efforts had managed to get the attention of the people who initially ignored the crisis. Hodges would later inform the ministers and health authorities on the other line that she had tested positive. They were all shocked by the information.

Of course, the concern may have been because a senator and the governor were now involved, but two specific individuals on the call were dumbfounded by the scope and intensity of this escalating public health crisis and vowed to give her everything she and her group needed...

“COVID Czar” Clay Marsh and Sen. Joe Manchin.

“It turned out that my husband took the brunt of it,” Hodges recounted. “We literally fought the devil in this house for about eight days. Not a demon, but the devil himself. And everything they say about this horrible disease is so true. It just ravages your body. We’re about 17 days out from his last symptom and it’s just a rebuilding process. You have to rebuild your health from here. The most difficult part of all this is knowing that I passed it to my household, and that’s unfortunate.”

And Hodges and her crew are not done. Aside from serving on the governor’s new task force aimed at eliminating disparities for African American COVID-19 infections, Hodges is still fielding calls from people who need help. She recently discovered that two more churches had members who attended the fateful service.

Aside from Sister Horton, another person who attended that service also succumbed to the coronavirus. Shortly after the service, another woman fell ill. She had body aches, chills and eventually lost 25 pounds. However, when she went to see a physician, she wasn’t tested for COVID-19. That story wouldn’t be very remarkable if it happened to anyone else. But the sick woman just happened to be Rev. Laverna Horton, who had just celebrated her sixth anniversary as pastor of Friendship Baptist Church.

I heard it was a beautiful service. Everyone was there...

Even the devil himself.

Editors Note: This article has been updated to note that Tiffany Samuels, Danielle Walker and Rahsaan Armand were also selected as commissioners on the African American Disparities Task Force as well as noting when Romelia Hodges informed the group that she tested positive for COVID-19.