“A safe world, in my opinion, would be one where other humans are not an existential threat. Love and value would have to fall in line for such a world to exist.” — William Wallace III, Philadephia, Penn.

text

This is the sobering half-wish offered on page 57 of Black Imagination, an amalgamation of black thought, poetry, rituals, inspiration, hope, and yes, imaginings of what healing might look like amid an inequitable existence. The project and resulting book—more aptly described by acclaimed author Kiese Laymon (Heavy) as “exquisite art in action” (h/t Amazon)—was conceived and curated by Seattle-based conceptual artist Natasha Marin and released on February 4, mere weeks before the coronavirus would become recognized as another crisis disproportionately affecting black Americans. Strikingly, it was also a date when Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd still walked among us (not to mention untold others), oblivious to the fact that a few months later, their deaths would send fresh shockwaves of rage across the country.

Suggested Reading

It’s now difficult not to wonder what Floyd might’ve been up to in his adopted home of Minneapolis—also my birthplace and former home—as Marin and I spoke by phone on May 21. An artist who considers working with people her chosen medium, she explained that she employs collaboration to help her create “immersive experiences of celebration, healing, beauty…turning an idea into something real that you can touch, smell, taste, feel.”

In conversation, Marin’s speech is frequently punctuated with words like “juicy” and “delicious,” words that evoke pleasure, nourishment, and a sense of comfort many of us have been denied since the onset of the pandemic—and certainly since the latest series of state-sanctioned murders that have reminded us of the callousness and disregard with which this country treats black lives.

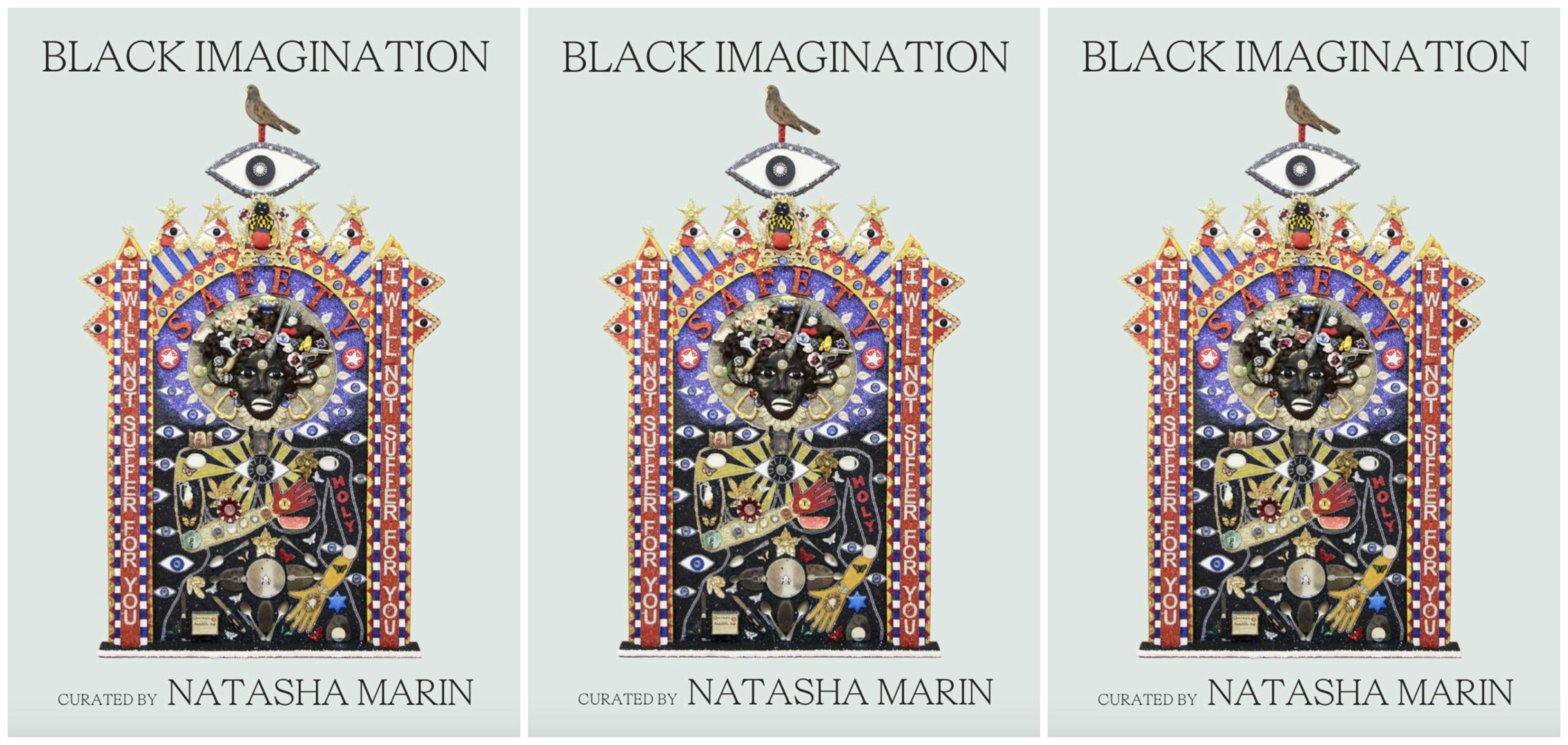

“Witnessing is sacred work, too. Seeing ourselves as whole and healthy is an act of pure rebellion in a world so titillated by our subjugation,” reads a quote from Marin in Black Imagination’s dust jacket. On its cover is a photograph of artist Vanessa German’s “Altar,” a sculptural assemblage featuring a saintly black female figure holding her hand over her heart, the image evoking the Yoruba-inspired religious artistry of the Caribbean (Marin herself is Trinidadian by birth). The words “I Will Not Suffer for You” flank each side of the tableau, which also includes the words “Safety” and “Holy” upon a background studded with “evil eyes.”

“There’s an evil eye right on the cover, so you don’t pick it up if you don’t need to; it’s not for everyone!” Marin laughed at the time, acknowledging that some might consider it “woo-woo,” before quickly adding: “But if you’re looking for this, it’s absolutely here, and it’s absolutely for us.”

To even the least spiritually inclined, the cover is a visual invocation; an invitation to participate in a sacred and transformative rite. Instinctively opening the book to a random page, Wallace’s words (quoted above) were the first to greet me—and were admittedly somehow exactly what I needed to hear at that moment; a statement that seemingly made sense of the infection—both literal and institutional—plaguing our country.

A week later, Black Imagination feels like essential reading. As such, I once again opened the book to another random page—33—which read:

In a world where I feel safe, valued and loved / There would be skyscrapers / Filled with chairs where / Cisgender / Able-bodied / Affluent / Straight / White Men / (and Women) / Could take several seats. / For months at a time. / We’d call them greenhouses. / To ensure their growth (and sweat) from sitting down. — Ebo Barton, Seattle, Wash.

It’s no coincidence that Marin and I connected over her work during May, which is Mental Health Awareness Month. While profoundly inspiring, Black Imagination was born from emotional trauma; Marin’s previous project, 2016's Reparations, went viral in its request for white people to leverage their privilege to assist people of color in easy, organic ways. That August, The Guardian described Reparations as “a half art project, half social experiment, the idea of which is this: people of color can request help or services, and others (white people, other people of color, anyone) could offer help.”

“I’m trying to create moments of solidarity between people of color, and between people of color and people who are white,” Marin told the outlet. “I’m not into polarizing. I’m into people working together for solutions…who can you help, who can you connect with, how can you offset your privilege.”

A seemingly simple request, but swiftly met with an irrational and deeply abusive onslaught of vitriol from those likely triggered by the concept of reparations alone.

“I really was quite surprised that my little organizing, art project-doing self would suddenly be the target of so much—so much—hatred. People have so much free time,” Marin scoffed. “After that little joyride, I definitely needed to do something for my soul. You know, there was a point in time where being called ‘nigger’ hurt—and then I did Reparations, and it was like, ‘Well, now I’m being called a nigger a thousand times before breakfast; let me get on with my day.’

“It definitely left a kind of raw, gravelly bitterness that didn’t feel indigenous to who I am,” she continued, sharing that she found both a needed escape and newfound inspiration in the writings of bestselling black female fantasists N.K. Jemisin, Tomi Adeyemi and Nnedi Okorafor. “I wanted to go and reclaim the territory of myself. So, I steeped myself in a juicy, hot sweet tea of Blackness, and I have been very reluctant to leave.”

Instead, Marin has done what comes most naturally: create art and a way forward out of often painful and difficult conversations. With Black Imagination, she invites us to join her in a space created with the sole intention of affirming our experience and cultivating our healing—by whatever means necessary.

“While I was sort of nourishing myself with literature, and music, and film and everything, I was also talking to black people,” she shared. “And really not talking, but listening…listening to black people share not just how they’re surviving, but healing and thriving and giving themselves permission to be joyful.”

“There was no effort required, at any point,” she later added in explanation of the process. “This work wanted to be done, and so it was, and it was a joy for me to do it—so joyful at every stage.”

There are no instructions on how to approach Black Imagination, and Marin hesitates to recommend any specific method, encouraging us to experience it in any way that most makes sense—as a classic text, daily devotional (my preferred method) or as the literary component of what is a still-evolving art exhibition.

“You don’t have to sit down and chuck through all the pages in a row. I do think it’s a radical thought, in terms of conceptual art: that we are sacred—and that we be treated as such,” she said. “We’re all experts at surviving while black—and for those of us who do more than that, please tell me how. I wanna know: Are you joyful today, despite all of this? Can I join you? Can you help me?

“The book is like an exhibition you can take with you—you don’t have to be alone,” she later added. “The book encourages dialogue: please see what the rest of us are thinking about, and engage and celebrate the you that is much bigger, and everlasting, and all-encompassing.”

With her words in my ears, I open another page—121—remarkably, another passage contributed by William Wallace III.

To heal, I step away from my own life and seek out the places where Life is at work. Whenever possible I drive thousands of miles towards storms or forest or incalculable spaces. And I breathe. And I listen. And I let go. And I’m free.

So what would Marin—in her wildest black imagination—collectively wish for us?

“I wish for all of us black and brown people that we give ourselves to ourselves, and each other,” she responded. “There is no territory—mentally, spiritually, emotionally, experientially—that is not ours, but we rarely give ourselves to ourselves…There’s nothing like the hug of Blackness; giving yourself to your Blackness; holding yourself with your Blackness; celebrating with and for your Blackness.”

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. Black Imagination is available in multiple formats from major booksellers now.

Straight From

Sign up for our free daily newsletter.