For Heather Heyer and her fellow anti-racist protestors, two years after Charlottesville.

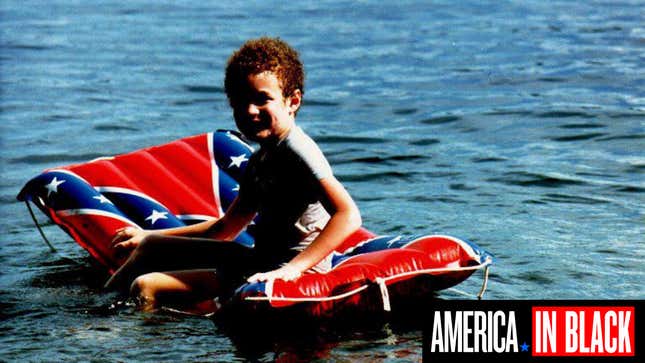

There’s a vacation photo of me, all grainy and saturated like the best ’80s snapshots. My messy red ’fro is damp, my smiling face is half in shadow, my feet are dangling in glistening water that spreads to the edges of the frame, and my skinny 8-year-old ass is bending the middle of a blowup raft with a huge Confederate flag on it. This picture sums up my youth: a mixed-race black kid alone in the middle of a lake, cluelessly floating on the whitest thing possible.

We lived in an upper-middle-class Jewish enclave outside of Boston until I was 15. I grew up around other kids with pale skin, thick lips, and curly hair, and didn’t have to think about blackness. MLK’s assassination felt like ancient history. I only knew the Confederate flag from the Dukes of Hazzard’s car. The same year that raft photo was taken, a white friend asked me if I knew any black people. I said, “No.” My black father was a couple of feet away in the driver’s seat.

My parents tried to protect my sister and me by softening hard truths, but the world started creeping in before we left Boston. I knew there were neighborhoods—usually blue-collar white ones—where “families like ours aren’t always welcome.” I knew my folks worried that I was getting undue attention at my white school, even when I was definitely acting up. But the racism was always subtle enough that it could be explained away. Like the time at Burger King, when an excited white man came up and started saying, “Vince Lombardi Rest Stop! I knew I recognized you guys. I saw you there last summer.”

He made me feel like a celebrity, so I wondered why my parents smiled curtly and kept us moving. He probably remembered us because we looked cool, not because we were an interracial family in 1980s New England...right?

Before we moved to Richmond, Va., I only knew my father’s Richmond; black Richmond: women in gravity-defying hats parading into the church on my grandparents’ corner, the high-school-sized HBCU where Grandpa got his degree in the ’40s, Grandma laughing when I asked why she called Grandpa “Turr”: “That’s my accent. I’m saying Terry, his last name...yours too!”

When we moved, I hoped to meet some more kids who liked rap music and finally figure out what to do with my hair. I was working with a surface-level knowledge of my blackness, but the statue of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee near our new apartment took it deeper.

I first saw the statue while rolling home from skateboarding with some new friends. It stands on a circular lawn at the center of a roundabout, and is maybe three stories tall, of a white man in old military garb, riding a tired-looking horse. I asked my father about it during dinner.

“That’s Robert E. Lee,” he said.

“Like from the Civil War?” I asked, through a mouthful of pasta.

“Yes,” Dad nodded.

“What side did he fight for?” I asked.

“The South, the Confederacy.”

“So, he tried to start a new country where people could keep owning slaves?”

“Yes,” said my father.

Then Dad said that the war was about more than just slavery. Something about states’ rights, too. I’m not sure if he was trying to calm me down or repeating something that a teacher in the Jim Crow South had told him, to calm him down 30 years before.

It didn’t work. Every time I took a left off my new block, the first thing I’d see was Lee’s horse’s ass. While this famous Confederate general was trotting South into a lily-white fantasyland, the back end of his horse pointed at the black neighborhoods to the North, where thousands of vibrant, beautiful, black lives were taking place. With every look at that horse’s ass, I understood that I was living one of those lives, and that there was more to black Richmond than church hats and accents. Racism becomes a part of you if you skateboard under it every day.

Robert E. Lee is one of four Confederates who are honored on Richmond’s Monument Avenue. When we arrived, the city was furiously debating whether a statue of black tennis champion and Richmond native Arthur Ashe should be erected there, too. Some locals call Monument Avenue “Loser’s Row,” but that doesn’t take the sting off the fact that one of the most affluent streets in the city was made to remind the black people who traveled it of the dangers of getting too uppity.

Living in Richmond, the past always felt like it was right there with me. Sometimes it was the happy “Henry? Is that you?!” moment of running into one of my dad’s old friends at the grocery store. Sometimes it was being at home and remembering that I was living in the shadow of a man who had fought so that people who looked like him could own people who looked like me. That constant reminder snatched a small bit of joy from everything I did. The proud moment when my mother cringed while I played my band’s demo? It wouldn’t have happened if Lee had his way. Graduating high school? I wouldn’t have even been able to read if things had gone differently in the 1860s.

The Civil War should be remembered, because white people should not be allowed to forget what their ancestors did and should be pushed to reverse the damage that slavery continues to cause. But the discussion should not happen on their terms because that leads to cities celebrating former slavers with huge statues.

Living with Richmond’s in-your-face, three-story-tall racism made me feel like I needed to leave. In becoming home, Richmond made me feel like I was not meant to thrive there. In showing me that to be black is to be dismissed, hated and threatened, Richmond made me proud to be black and made me want to achieve more.

Before I left, my band toured Europe for a month. In Germany, most of our shows were in small community centers, concrete buildings covered in the punk-rock folk-art of graffiti and fading concert flyers, with a knee-high stage, a grimy bar, and a kitchen where the promoters cooked us vegan slop before we played. Even though I’ve never craved hot sauce as much as I did during those meals, I felt like I was living out a daydream.

One night, we played in a converted old train station and hung out there after the show. By the bar, a local who looked like a blond lion in camo shorts was beating me at foosball. After he scored two goals in rapid succession, I took a slug of beer and said, “This place is cool.”

“The Nazis built it,” he said.

“What?” I asked

“The Nazis built it,” he repeated, slower, probably thinking I couldn’t understand his light accent.

“Right,” I said.

“They’d load people onto the trains outside and send them to the concentration camps.”

He threw a thumb over his shoulder at the quaint-looking train tracks I’d been admiring earlier.

“Wow,” I said.

“Yah,” he nodded. “This is what they did with all of the buildings from the Nazis. They turned them into community centers. Art spaces. Good places.”

Germany wanted to remember, too. But they didn’t want to glorify the memory. They repurposed it and used it to move forward.

Back in Richmond, there was a protest at the foot of the Lee Monument. I’m not usually the marching type, but I couldn’t miss this one. I was standing in the grass at the edge of a group of black and white activists, just being glad to be around people I agreed with, when a dented green pickup truck stopped in the roundabout. The truck belonged to one of my white skater friends’ dads, a stubbly guy who I recognized from a framed photo on his mantle: him grinning and wielding a signed Rush Limbaugh book. Today, he was peering across his front seat, calling out, “Hey, Chris.”

I nodded to him.

Then this 50-year-old man yelled at me, “Get a life!”

No matter what that city tried to do to me, I had a life, and I was ready to go live it. I looked him in the eye and flipped him the bird before he drove off, looking surprised in his backfiring truck.

When my parents moved a few years ago, and I found the Confederate flag raft photo in a shoebox under a picture of my dad in a tweed bell-bottom suit.

“Mom,” I shouted. “What is this?”

She looked stricken and started trying to smooth it over, “It was just there and…everyone was playing…that show you and Dad used to watch, Dukes of…”

I gazed at my younger self, chillin’ on a symbol of hate. Younger me would have been angry and embarrassed. Now, I was ready to look back, own it, and laugh.

“This is so wrong it’s right,” I said. “Will you scan it for me?”