When Eric Garner died after being put in a chokehold by then-New York Police Officer Daniel Pantaleo on July 17, 2014, his daughter Erica Garner immediately became an activist of the highest caliber. She organized marches, wrote articles, and stood up to demand a conversation with President Obama at the presidential town hall on race in America in 2016.

Shortly before she died, Erica described the hardships and the mental and physical toll of her activism. “I’m struggling right now with the stress and everything. This thing, it beats you down. The system beats you down to where you can’t win,” she shared. Three weeks after giving this statement, Erica died from the brain damage she suffered following a heart attack. She was just 27 years old.

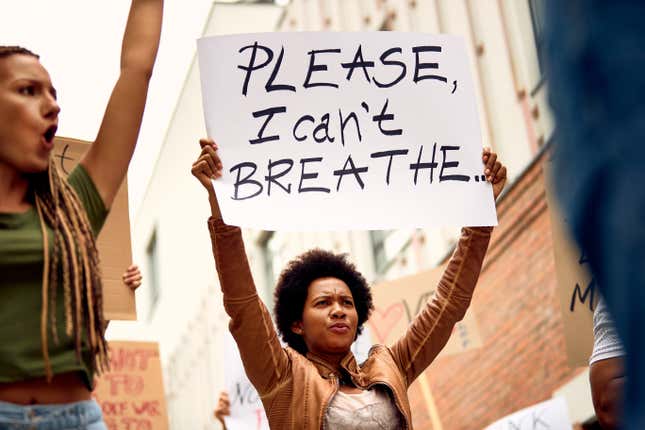

Erica Garner’s story, and others like it, including the very similar chokehold killing of George Floyd, has even prompted a United Nations’ call for reparations. This call was assembled not just for the reparations due per enslavement but for structural racism, including police violence, through methods that include but are not limited to, “formal apologies, truth-telling commissions, and reparations of various other forms.”

Here in the United States, the call for action should start with support for the Mike Brown Bill, an initiative led by Lezley McSpadden Head, the mother of Michael Brown, supported by the Michael O.D. Brown We Love Our Sons and Daughters Foundation, and the Thurgood Marshall Civil Rights Center at Howard University. While the bill includes a broad call for the end of police violence, racial profiling, and police militarization, it also seeks to address the need for mental health treatment and healing as a community.

This proposal, included as part of the BREATHE Act proposed by the Movement for Black Lives, specifically creates a fund to promote healing for those impacted by the reverberating effects of police violence, like Erica and Lezley, and so many countless others. We know that the trauma experienced by victims of police violence and their family members is great. The majority of cases do not generate significant media exposure or public support, and those families may struggle to pay legal fees, access affordable mental health counseling, or even meet basic needs. This is especially true for victims tasked to serve as the primary breadwinner and head of the household. As for those who fight and even manage to survive financially, the pressure to advocate and relive the worst moment of one’s life can result in severe PTSD or other mental health challenges. As demonstrated by Erica’s story, the stress itself can prove to be deadly.

These challenges are not only an additional burden to families of those killed by police protesters. Anyone harmed by police violence should receive healing, especially if they have documented proof. In all likelihood, further research will reveal that essentially the entire Black community is impacted. Studies have shown that incidents of police brutality increase adverse health consequences that negatively impact the mental health of people throughout the Black community whenever one of these incidents goes viral. The ramifications include but are not limited to job loss, sleeplessness, exhaustion, anxiety, and the incapacity to concentrate. This is all brought on by the accumulation of acute depression and stress. The epidemic of police violence, much like COVID-19, fails to have the same impact on White America as it does people of color in every community across the country.

Meanwhile, as the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion has highlighted the importance of creating social and physical environments that promote good health, increase quality-of-life outcomes and reduce risks as part of the ‘Healthy People 2020’ initiative,

In May 2015, following the aftermath of an especially horrible episode of police violence in Chicago, local activists were able to pass a reparations bill. The bill included the creation of the Chicago Torture Justice Center where those impacted by police violence have access to specialized traumatic counseling services, the creation of a permanent public memorial, a public apology, and financial compensation to those directly impacted for medical and other expenses. This is not unique to Chicago—North Carolina, Florida, and other states have delivered monetary reparations to victims of racial violence. These communities realized that it’s better to invest in the health of its people than pay the costs of not caring, as inevitably the devastating effects hurt us all.

Malcolm X famously stated: “If you stick a knife in my back nine inches and pull it out six inches, there’s no progress. If you pull it all the way out that’s not progress. Progress is healing the wound that the blow made.” People and institutions that harm Black people should take concrete action to repair the harm done. Police departments must publicly acknowledge the harm done, make official apologies, and commit resources to communities who have been forced to suffer violence at their hands. Coming from Congress, the creation of this fund is only the beginning. But it will be a strong beginning to send the message to the rest of the country that the time for healing has begun. We must ask our government the hard question—what concrete actions will you take to REPAIR the harm, and ensure we don’t REPEAT the loss of Black lives at the hands of police violence? This is a formal call to #REPAIRnotREPEAT the incidence of police violence against people of color in this country.

Lezley McSpadden Head is president of the Michael O.D. Brown We Love Our Sons and Daughters Foundation, and Justin Hansford is the executive director of the Thurgood Marshall Civil Rights Center at Howard University School of Law.