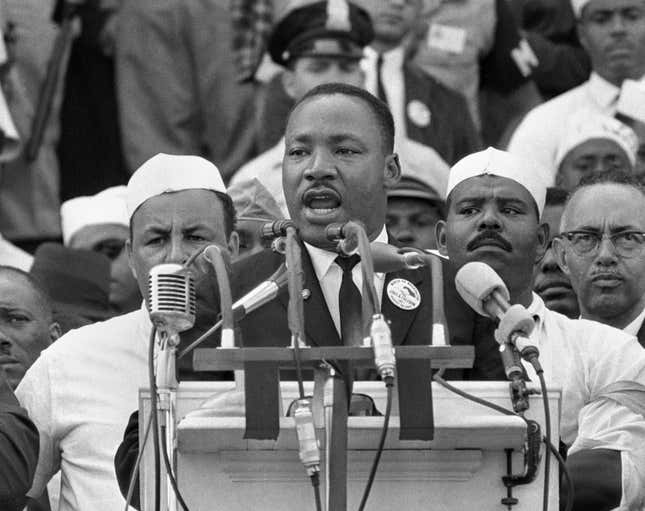

In a 1968 speech just prior to his death on April 4, Martin Luther King Jr. appeared to articulate the next phase of the fight for equality in America. It wasn’t focused on equal rights or the plight of African Americans in education in the wake of Brown v. Board of Education—it focused on black economic empowerment and reparations.

In this little-known speech, King referenced New Deal land grants provided to “white peasants” through an act of Congress. These same white families were given access to land grant colleges that trained them to work the land and establish local farms and businesses; they were then given government-backed, low-interest rate loans to supply the capital necessary to expand their businesses, hire more workers, and purchase equipment. Later, those families received subsidies to not over-farm the land. White wealth wasn’t an accident.

Dr. King called for black people coming to Washington to “get our check.”

King understood that white wealth came from government support and argued that those advantages made it impossible for black people to build the same wealth. Structural racism touches every aspect of black people’s lives, and it affects them most in their pocketbooks—leaving our national economy weak and unstable.

So how can we tackle something so big but so essential to our collective well being?

King was right: We need a race-centered economic empowerment package for African Americans that builds generational wealth and accounts for not only slavery but the decades upon decades of economic pillaging.

Reparations today should include things like access to government contracts, low interest-rate loan guarantees, access to higher education and vocational training, jobs that pay a living wage, and subsidies to repay back wages owed to the descendants of enslaved black people to close the national wealth gap—and it’s essential that our government leads with bold action.

Government subsidies were an economic floor for white Europeans in our nation’s earliest days and the basis upon which white privilege took root.

Colorlines, a publication run by Race Forward, reported that “the U.S. government spends billions subsidizing farming in America, yet Black farmers today receive only one-third to one-sixth of that ... and the Southern Rural Development Initiative found that less than 1 percent of agriculture subsidy payments between 2001 and 2003 went to Blacks, Native Americans and Asian Americans.”

Worse, inequality has only grown since the Great Recession wiped out any gains black people made in the post-civil rights era. Today, without intervention, it would take an African-American household 228 years to build the same amount of wealth as our white counterparts.

With numbers that bleak, the government has to step in. And research shows it could make a difference, just like it did for white people in the New Deal and over the last century.

The Kaufmann Foundation found businesses run by people of color are more likely to employ people of color. Put simply—a mere 10 percent increase in the number of people of color-owned businesses could create one million new jobs for people of color. More jobs paying a living wage means greater spending among people of color and low-income people, which will in turn further support local business, increase the tax base in low-income communities, allow city and municipal governments to improve education systems, and so on. Hence—a reparations program that increases the size and number of black-owned businesses would have a huge impact.

Despite presidential candidates beating the drum on this critical issue, Washington is moving slow. But organizations like mine—Living Cities—are testing how funders and social entrepreneurs can begin the process using financial investments at a smaller scale.

Philanthropy is trying out access to capital as an avenue for reparations, beginning with investments in historically marginalized communities in Minneapolis; St. Paul, Minn.; and New Orleans. In Minneapolis, we partnered with Twin Cities Corridors of Opportunity Initiative to help train entrepreneurs of color. Those entrepreneurs now employ more than 2,000 people making $12 an hour. Meanwhile, in New Orleans, investments through the BuildNOLA Mobilization Fund have already helped create more than 100 family-sustaining jobs for people of color. These results show potential, but philanthropy cannot possibly provide the scale of government.

Imagine if our national government implemented programs like this on a larger, targeted scale. This is a small start compared to what Washington could do, but it’s only the beginning. Legislation already exists to help establish a commission to study and shape a vision for making reparations a reality. These small experiments offer a roadmap to finally ensuring equality and justice for all of us.

Now more than ever, we must leverage the power of all sectors—political, governmental, non-profits, private industry and more—to close racial gaps in our society. Collectively, we must reprioritize how we create opportunity, and for whom. King’s words offer a vision. Combined with data and real action at the federal level, these might be the tools needed to push America to achieve it.

Demetric Duckett is Associate Director of Capital Innovation at Living Cities. Demetric is a thought-leader in the domestic impact investing field, accelerating the adoption of innovative financing for the benefit of low-income people and the communities in which they live.