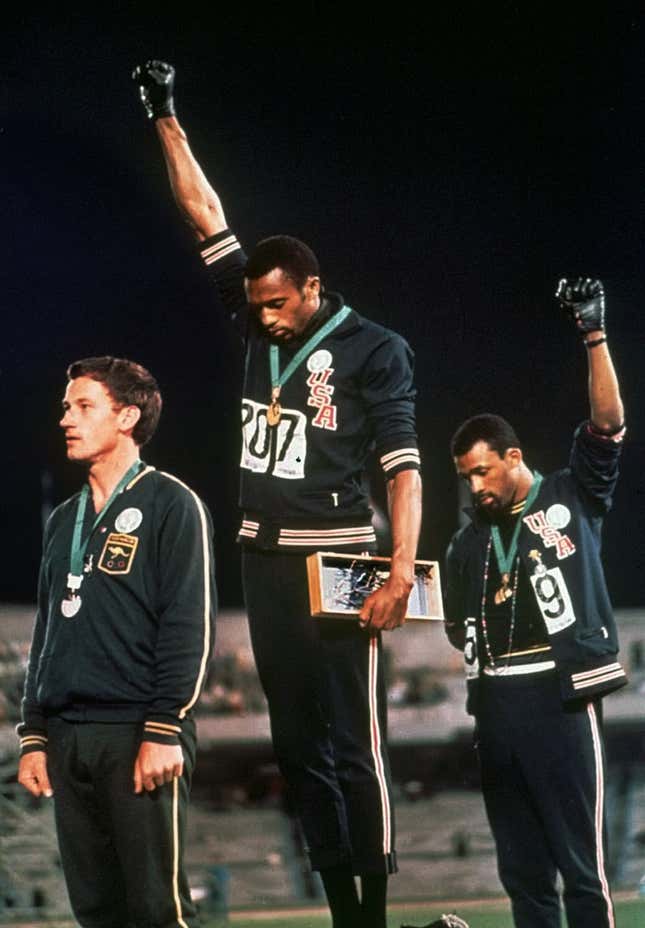

Decades before Colin Kaepernick was taking a knee on the football gridiron to protest racial injustice, Olympic sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos were raising a fist on the winners’ stand at the 1968 Olympics. Much like Kaepernick, Smith and Carlos were expelled for their actions. Now, it looks like the Olympics is prepared to issue a mea culpa of sorts.

On Nov. 1, a little more than 51 years after the Olympics organization expelled them for their protest against racial oppression, the Olympics will be inducting both Smith and Carlos into the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Hall of Fame, NBC Sports reports.

As the Washington Post explains:

Smith and Carlos were responsible for one of the most recognizable moments in Olympic history, raising their fists in protest on the medals podium at the 1968 Summer Olympics. They have both previously been bestowed with a long list of honors, including induction into the USA Track and Field Hall of Fame.

Their exclusion from the USOPC’s hall highlighted the thorny relationship the organization has had with the two sprinters for decades. At the 1968 Games in Mexico City, the USOPC — which was known as the U.S. Olympic Committee until changing its name earlier this year — succumbed to pressure and sent the men home following their controversial protest.

The year 1968 was a turbulent time in the world. Just months before the Olympics took place in Mexico City, Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated, young men and women were still fighting and dying in the Vietnam War, and race relations were fraught, not only in the U.S. but abroad.

Some athletes were thinking about boycotting the Olympics altogether, the Post notes. Athletes were upset about the inclusion of apartheid South Africa and Rhodesia in the Games; were calling for the removal of the then president of the International Olympic Committee amid accusations of racism and anti-Semitism; and were demanding the hiring of more black coaches.

After Smith broke the world record in the 200-meter race, winning gold, and Carlos took third place in the race, the two took their places on the medal stand and raised their fists as “The Star-Spangled Banner” played.

Reaction to the perceived outrage was swift, as the Post explains:

That sparked a swirl of activity from Olympic officials. The USOPC initially decided against a suspension, intending to issue a warning to the rest of the American athletes competing in Mexico. The International Olympic Committee demanded a stronger response, though, fearing “that racial dissension might spread to other delegations if USOC refused to suspend Smith and Carlos,” according to a dispatch sent from the U.S. Embassy in Mexico City at the time.

Olympics officials expelled Smith and Carlos the day after their protest.

For years, “Smith and Carlos felt ostracized from the Olympic community,” according to the Post, “ but have increasingly been heralded as both iconic activists and accomplished athletes. In 2016, the two were invited to visit the White House and President Barack Obama, along with that year’s U.S. Summer Olympics team.”

Now, comes their induction in the Hall of Fame, five decades later.

As sports writer Dave Zirin, who co-wrote Carlos’ autobiography, told the Post:

“One could be forgiven for rolling their eyes at the USOC finally—after 51 years—catching up with the rest of the world.”