On Saturday, 200 rare and never before seen works by the famed artist Jean-Michel Basquiat opened to the public at Chelsea’s Starrett-Lehigh building. The “King Pleasure” exhibition, curated by Basquiat’s sisters Jeanine Heriveaux and Lisane Basquiat, along with their stepmother, Nora Fitzpatrick, is an extension of his legacy, and a rare glimpse behind the artist through the eyes of his family. While the idea came to them in early 2017, the project was paused soon after, as the world began to reckon with incidents of social injustice, and later a global pandemic. But the present moment felt like the right time for the women behind the iconic man to tell his story.

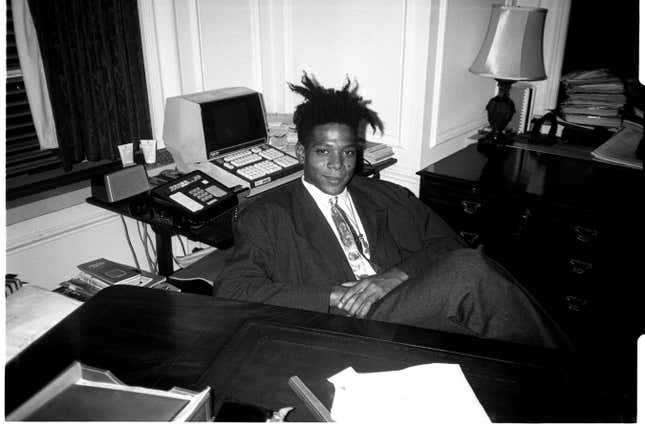

“The theme is really Jean-Michel as a human being,” Heriveaux told NBC News. “Before he was an artist, he was a son. He was a brother. He was a nephew — and we’re trying to show that human side of Jean-Michel and where he came from, his childhood and our personal relationships with him.”

In addition to the artist’s works, the exhibition which spans more than 15,000 feet also includes recreations of rooms of his childhood home, his NYC studio, and a nightclub frequented by Basquiat. All pieces to the artist’s personal puzzle, and the backdrop to his creative inspiration.

While Basquiat grew up in Brooklyn, New York, the artist has roots that trace back to Haiti and Puerto Rico. The family’s background played an epic part in Basquiat’s own cultural identity. Much of his work throughout the 1980’s including pieces such as, “Hollywood Africans,” “Big Joy,” and “Gold Griot,” serve as cultural commentary about the portrayal and reception of Black people in society. His artistic style is possibly most easily identified by his incorporation of graffiti. Basquiat is credited with bringing graffiti into elite art spaces, and being recognized as a legitimate art form around the world.

Basquiat’s Haitian and Puerto Rican background also painted his real life experiences, especially when it comes to interactions with the police. His sister Heriveaux recalls the difficulties the artist had doing simple things in the city like catching a cab, but also remembers how shaken up her brother was learning of the death of Michael Stewart in 1983. Stewart died at the hands of police who beat and hogtied him for drawing graffiti on New York City subway tile.

“It shook him so much,” Heriveaux said. “He stated that he thought that could be him. Whatever thoughts that were occurring in his mind … he sketched about them. He painted about them.”

It was this story and others like it that inspired Basquiat to use his art to communicate to and uplift those faced with similar day to day challenges.

“I see a generation of people who are confronting challenges with the way that this world culture handles racism, classism — you know, social issues,” Lisane Basquiat said, “and I think that those issues are disturbing to younger people, and Jean-Michel speaks to those.”

Basquiat did not however keep his art stuck in struggle. The famous crown symbol he is most known for was also designed to empower Black and Brown people, and was later adopted by cultural icons like Jay-Z and Biggie, evidence that Basquiat’s influence lives long after his death.