A few blocks away from Tulsa’s Greenwood neighborhood sits the city’s oldest existing cemetery, Oaklawn. On Monday, scientists and forensic anthropologists scoured the cemetery with ground-penetrating radar, looking for signs of a mass grave that could hold the remains of hundreds of black residents killed during the 1921 Tulsa massacre.

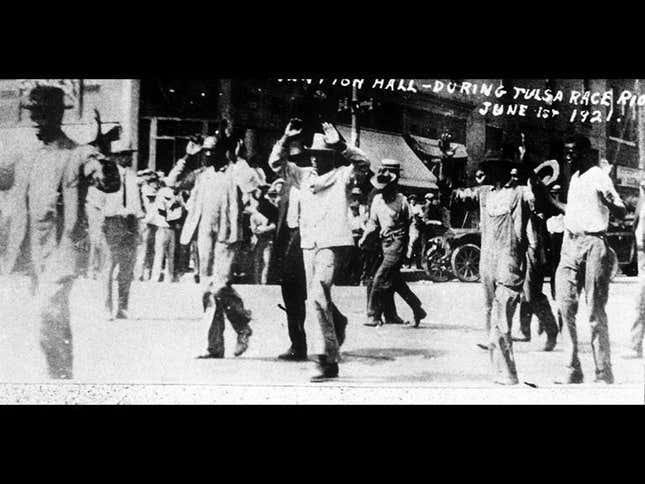

As the 100-year anniversary of the massacre approaches, the city is facing increased pressure to address its turbulent racial history in a way it never has before. A major part of that will be resolving what happened to the hundreds of people slaughtered at the hands of the violent white mob that destroyed what was known as Black Wall Street.

Tulsa Mayor G.T. Bynum announced last year that he would open an investigation into the city’s mass graves, comparing that inquiry to a murder investigation, the Washington Post notes.

“If you get murdered in Tulsa, we have a contract with you that we will do everything we can to find out what happened and render justice,” Bynum told the Post. “That’s why we are treating this as a homicide investigation for Tulsans who we believe were murdered in 1921.”

But it’s more accurate to think of the massacre on Black Wall Street as an act of domestic terrorism.

Greenwood, a self-contained and reliant neighborhood, was one of the most prosperous black communities in the country in the early 1900s—prompting Booker T. Washington to refer to it as “the Negro Wall Street.” And it was targeted by a white mob specifically for that reason.

This is how a 2018 Washington Post report describes what happened:

For two days beginning May 31, 1921, the mob set fire to hundreds of black-owned businesses and homes in Greenwood. More than 300 black people were killed. More than 10,000 black people were left homeless, and 40 blocks were left smoldering. Survivors recounted black bodies loaded on trains and dumped off bridges into the Arkansas River and, most frequently, tossed into mass graves.

The question of where those mass graves are located has never been resolved. Mayor Bynum said last year that the city is obligated to find out.

Tulsa city officials have known for at least 20 years about specific sites, including Oaklawn, that may contain mass graves. State investigators and archaeologists began exploring claims of mass graves in 1998—working off of eyewitness recollections and using electromagnetic induction and ground-penetrating radar to confirm anomalies in the environment that would suggest a mass burial. Excavation was even recommended by a 2001 state-ordered commission to investigate the Tulsa race riot.

But mayor after mayor passed on the recommendation—citing concerns over costs or disturbing the bodies buried.

Between now and January, the city hopes to complete its ground-penetration radar investigation of Oaklawn, as well as Newblock Park, and Rolling Oaks Memorial Gardens, which was previously known as Booker T. Washington Cemetery.

But it’s only the first step.

If evidence of mass graves are found, city officials and an oversight committee will then determine whether to excavate, reports the Post. The Oklahoma medical examiner’s office will also get involved to determine the cause of death, a necessary step to determine whether the remains found were likely victims of the massacre, or from a Spanish influenza outbreak that hit the city two years before.

If the mass graves are linked to the rampage, the city will need to determine how to identify and store the remains, as well as how to commemorate the site.

Still, the long-overdue search for the city’s mass graves is an important move toward acknowledging the city’s violent past, and understanding how it shapes its current climate.

As Tiffany Crutcher, sister of Terence Crutcher, the unarmed black motorist shot and killed by a white Tulsa police officer in 2016, told The Root last year, “The same culture in Tulsa that burnt down black Wall Street is the same culture that killed my twin brother, and it hasn’t changed.”