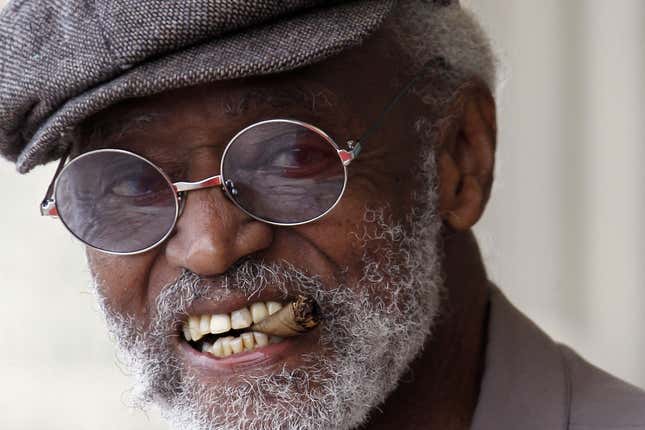

Actor-writer-director-composer Melvin Van Peebles—a Renaissance man who promoted Black economic empowerment and helped usher in a new era of Black filmmaking with his best-known work, the 1971 film Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song—died Tuesday night at 89.

His death was confirmed by film distributor Criterion Collection in a statement from the family. No cause of death was given.

In an unparalleled career distinguished by relentless innovation, boundless curiosity and spiritual empathy, Melvin Van Peebles made and indelible mark on the international cultural landscape through his films, novels, plays and music. His work continues to be essential and is being celebrated at the New York Film Festival this weekend with a 50th anniversary screening of his landmark film Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song...

His son, noted director and frequent collaborator Mario Van Peebles, said of his legendary father: “Dad knew that Black images matter. If a picture is worth a thousand words, what was a movie worth?” he said in the statement. “We want to be the success we see, thus we need to see ourselves being free. True liberation did not mean imitating the colonizer’s mentality. It meant appreciating the power, beauty and interconnectivity of all people.”

Melvin Peebles was born Aug. 21, 1932, on the South Side of Chicago. (He added “Van” to his last name while living in Amsterdam.) After graduating from high school in 1949, he enrolled at West Virginia State University but transferred to Ohio Wesleyan University. Days after graduating in 1953 with a degree in literature, he joined the Air Force, where he was a B-47 flight navigator for three-and-a-half years.

Out of the Air Force and married to a German woman, the photographer Maria Marx, Van Peebles moved briefly to Mexico, where his son Mario was born. (The couple would also have a daughter, Megan, and another son, Max.) The family soon moved back to the U.S., settling in San Francisco, where Van Peebles worked as a cable-car driver. He also painted and wrote short stories about his experiences.

After making a series of short films, he tried to get hired as a director in Hollywood but was offered only jobs as an elevator operator and a dancer. Van Peebles decided to move with his family to the Netherlands in 1959 and take graduate courses in astronomy while also working at the Dutch National Theater. (His marriage would end overseas, and Maria would move back to the States with the children.) Van Peebles dropped astronomy after the Cinémathèque Française invited him to Paris to screen his short films there.

Van Peebles, who mastered the French language in Paris, was hired to translate Mad magazine into the language. He also began writing plays in French. Van Peebles made his first feature-length film, The Story of a Three-Day Pass, in France in 1968. That movie, about a Black American soldier’s relationship with a white French woman, caught the attention of Hollywood producers. (Although Van Peebles would eventually move back to the States, his ties to France continued throughout his life, and he was awarded the French Legion of Honor in 2002.)

Van Peebles’ first U.S. film was the Columbia Pictures 1970 cult comedy Watermelon Man, the story of a bigoted white insurance salesman (played by Godfrey Cambridge) who wakes up one day to find that he has turned Black and is quickly ostracized by friends and colleagues. Van Peebles became the first African American to direct a mainstream feature film, but the milestone didn’t come without complications. The studio asked him to shoot two endings—one in which Cambridge’s character becomes a Black militant after his experience, and the other in which he wakes up to find it was all a dream. Van Peebles dealt with the situation by “forgetting” to shoot the second ending.

After that experience, Van Peebles decided that he wanted full control over the production of his next film. In 1971 he released the groundbreaking, sexually explicit feature Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song. Dedicated to “all the Brothers and Sisters who had enough of the Man,” it was about a Black man on the run from racist police officers.

Van Peebles funded the movie with his own money and a $50,000 loan from Bill Cosby. He also wrote the screenplay and score and edited the movie. Baadasssss Song—an insider’s view of the Black experience—would end up grossing $15 million. It also helped usher in the blaxploitation era of films created for Black audiences and featuring gritty, controversial characters that often reflected harsh stereotypes.

The response to the film at the time—the Black Panthers’ Huey Newton reportedly calling it the “first truly revolutionary Black film,” while film critics bashed it—didn’t make Hollywood more receptive to Van Peebles’ filmmaking style, and he turned to other artistic outlets and pursuits. (In 2010, the African American Film Critics Association would honor Van Peebles for his work and influence in Black film.)

He released the studio album Brer Soul in 1969. Often cited as a forerunner of rap, it featured a vocal style known as sprechgesang, in which lyrics are spoken over music. He wrote and composed two Broadway musicals, Ain’t Supposed to Die a Natural Death (1971) and Don’t Play Us Cheap (1972)—both of which were nominated for Tony Awards. Ain’t Supposed to Die won several Drama Desk Awards.

Van Peebles was widely praised for his film scores. He was given an NAACP Award for the music for Watermelon Man; he also received two Grammy nominations for the score of Ain’t Supposed to Die. While still unknown at the time, the Chicago-based band Earth, Wind & Fire performed the music for Sweet Sweetback, which helped launch the band’s career.

Van Peebles also continued to pursue his literary and financial interests. In 1984 he received a Daytime Emmy Award for writing the episode “The Day They Came to Arrest the Books” for the CBS Schoolbreak Special. In 1986 he penned a well-received self-help financial book, Bold Money: A New Way to Play the Options Market, after becoming the first Black trader on the American Stock Exchange.

His son Mario, who at age 10 had a small role at the beginning of Baadasssss Song, would explore the making of his father’s movie in the 2003 documentary Baadasssss! In 2005 Melvin discussed his filmmaking in the documentary How to Eat Your Watermelon in White Company (and Enjoy It). Melvin and Mario would also collaborate on a number of projects, including the 1989 film Identity Crisis.

In 2009, Van Peebles published the graphic novel Confessions of a Ex-Doofus-Itchy Footed Mutha, and produced and directed a film by the same name. He also pushed to make Sweet Sweetback into a musical, an early version of which was shown at the Apollo Theater in 2009. That same year, he wrote and performed in a stage musical, Unmitigated Truth: Life, a Lavatory, Loves, and Ladies, which showcased both his previous songs and new material.

When he was 75, Van Peebles spoke about what it was like for an African-American male growing up in the 1940s and ‘50s: “ ‘Boy’ was when you were a kid, and when you got old, ‘uncle.’ They’d never call you a man.” Of his own journey past that in-between period—the threatening “virility stage,” as he put it—he said: “Little old ladies used to pull their purses close to them when you’d walk by,” he said. “Now they smile.

“It’s all how you look at stuff,” he added. “And America gives you a lot of stuff to look at.”

Monée Fields-White is a freelance writer and editor based in Los Angeles.