After leaving high school to support his family, Rahkeem Morris, a Black millennial, eventually went on to found HourWork, a Boston-based tech startup that helps match employers with hourly workers.

The company has achieved incredible results for its customers, which include many of the country’s largest fast-food chains. But, when Morris originally approached venture capitalists, he was repeatedly turned down — and not because the business idea was faulty, says Jason Allen, portfolio director for MassMutual’s Impact Investment.

As Morris’ unsatisfying fundraising story shows, some investors may make inaccurate assumptions about what the persona of a successful entrepreneur should look like based on their past experiences.

HourWork is one of more than a dozen companies now thriving in part due to the impact of the MassMutual Catalyst Fund (MMCF), which invests in diverse-led and rural companies. Their success reveals three overlooked truths about impact investing.

Investors’ biases have the potential to limit their vision — and their returns.

When Allen saw HourWork’s pitch, he immediately recognized its potential. He had worked hourly gigs before — mainly folding clothes at retailers like J. Crew and Gant — so MMCF was one of the first to invest in HourWork, which has since raised more than $10 million and been adopted by fast food franchises across thousands of locations.

As Morris’ frustrating fundraising story shows, investors are oftentimes shaped by their personal experience — and their assumptions about what a successful entrepreneur looks like. Often, says Allen, the mental model is an Ivy League grad coming from a well-established company and setting up shop in a major city.

When someone doesn’t fit any part of that model, like Camille Martin, a Black co-founder of Seaspire Skincare in Cambridge, MA, it can be hard to attract attention. Martin has a PhD in chemistry from Northeastern University and developed a class of new clinically validated cosmetic ingredients demonstrated to be safer and more sustainable than many commercial products on the market. “She had all the credentials but still struggled to raise money,” says Allen.

This was exactly why MMCF was created. Launched in 2021, MMCF was charged with building a portfolio of early- and mid-stage companies with investment sizes of $250,000 to $2.5 million each. After Seaspire received MMCF funding, other institutions took notice, attracting even more investment and eventually landing the start-up in Sephora’s beauty accelerator.

Access is about more than capital.

Raising capital is a fundamental part of entrepreneurship — and one that isn’t distributed equally. “What I typically saw in my experience in venture capital before this role is that, as an example, there’s a product manager that comes out of the tech industry, and they have friends, family, or a network that can provide access to capital to deploy for an early enterprise,” says Allen. “For many Black and rural founders we invest in, we don’t typically see that.”

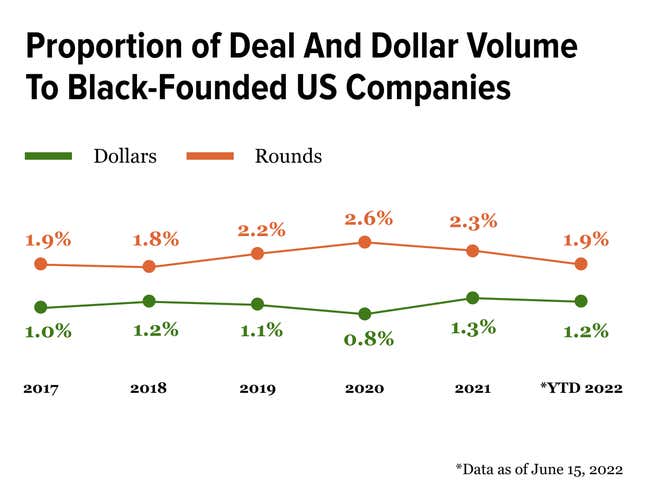

The statistics support that observation. Startups with at least one Black founder received 1.2% of overall venture dollars invested in the US in 2022. Breaking that down by state, for example, only .4% of VC funding goes to Black founders in Massachusetts, Allen says.

MassMutual’s $300 million commitment — $150 million for the Catalyst Fund and $150 million for the First Fund initiative — aims to level the playing field for entrepreneurs who are Black, Latino, Indigenous, or based in rural areas. But, the company recognizes that the problem can’t be solved with money alone.

Small business owners need help with every aspect of running a company, including hiring staff, developing a budget, consulting with a legal team, accessing subject matter experts, and networking with industry insiders. Even obtaining the necessary insurance can be a divisive step in the growth process.

Impact investing isn’t philanthropy.

A myth that Allen often encounters is that MMCF is a charity. It’s not. “These are investment dollars, which tells you the commitment that MassMutual has,” he says. “We’re not just giving money away.”

Applicants undergo a screening process that’s fairly rigorous. “If companies make it through our process, we usually see other institutional investors come into the round,” he says. And that can have tangible benefits.

Take Rapid Liquid Print, a 3D printing and injection molding company that was birthed at MIT’s Self-Assembly Lab before going private with its combination of polymers and software that develop products in zero gravity. MassMutual was especially impressed by the company’s car gaskets, and the Catalyst Fund’s participation may have created greater awareness of the opportunity for other organizations to follow, “which helped pull the investment round together,” says Allen.

And while seed funding is typically the most difficult for founders to get, MMCF recognizes that entrepreneurs need continuous support, not just a one-time injection of money. So, it funds through the first $5 million of revenue when the company has identified a market and customer segment to pursue. “Running a company, no matter what size, is really hard,” says Allen.

MassMutual has committed $300 million to impact investing, and Allen hopes that its seed funding will help create even more networks of investors who have the same guiding principles as the MassMutual Catalyst Fund. Says Allen, “We’ve got these companies that have gone on to be successful and that creates another ecosystem of diverse and rural opportunities for people to invest in.”

Concentrating capital in Black-led businesses, MassMutual is investing outside the status quo. Discover how.

This post is a sponsored collaboration between Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance Company (MassMutual) and G/O Media Studios. MM202607-305571.

*Source: Crunchbase