He was born “the poorest of Harlem’s poor” in 1944, and spent decades hustling before breaking into a legitimate trade. Nearly 75 years later, his designs for Gucci were the ones to be seen in at this year’s Met Gala. He launched “logomania” before it became a phrase, disrupting luxury fashion by infusing it with his own inimitable style and putting it on the backs of black and brown people. He has seen the iconic enclave that is his beloved Harlem at its height, and watched it be torn apart and rebuilt anew—much like his fashion career. Dapper Dan was made in Harlem, but his influence now spans the globe, creating designs coveted by some of the world’s most famous faces and catalyzing barrier-breaking changes at the world’s most exclusive fashion houses.

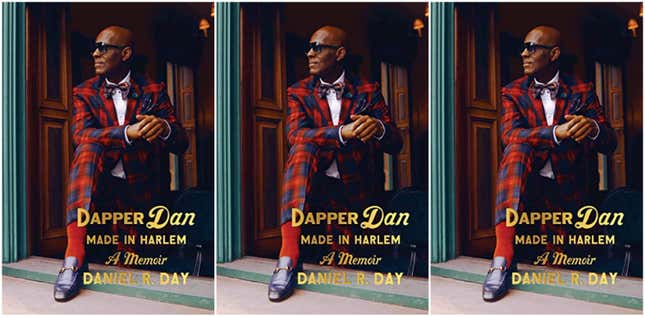

Released on Tuesday, Made in Harlem: A Memoir is Daniel R. Day’s telling of his remarkable and unlikely evolution into the world-renowned designer we know as Dapper Dan, a man who has never abandoned his roots, instead choosing to share his success with the neighborhood and people he loves. And yet, for all the fashion world’s fascination with his designs, Day’s story is even more fascinating—in fact, it’s a pretty wild ride.

The legendary designer was on hand at the 2019 Essence Festival and stopped by the SheaMoisture “House of Hair” for an intimate chat with friend and fashion activist Michaela Angela Davis, who opened the conversation by thanking him for being such an inspiration to black women, in particular.

“You’ve been unapologetically black since before we even had that language,” Davis, dressed head to toe in Gucci, said in her introduction.

For his part, Day credits his newfound revival—which now includes a partnership with Gucci, a book deal and an upcoming biopic—to Black Twitter. The social media community rallied (as we do) for rightful recognition of the designer when the same luxury houses that once put his 125th Street Dapper Dan’s Boutique out of business were suddenly sending ripoffs of his ahead-of-their-time designs down the runway under the guise of “homage.”

“Everybody wanted to pay homage to Dapper Dan, but nobody wanted to pay Dapper Dan,” he quipped. In response to the criticism, Gucci stepped up to the plate to make it right. The rest is now fashion history.

Much like his memoir, Day is more than stylish on the surface—despite being so effortlessly cool that somehow even the venue’s drinks happened to match the harlequin-print Gucci shirt he wore on Saturday. Riffing on everything from global and community economics to tokenism, Day spoke plainly about the naïveté of many armchair critics demanding change in the fashion industry, pointing out that every major boycott black people have waged has been successful except those recently waged against luxury fashion houses—understandable, since we were never their primary base or intended customers.

Day doubled down on those comments when I grabbed a few moments alone with him after the talk on behalf of The Glow Up.

“A true changemaker has the responsibility to know the dynamics of [the] global fashion industry,” he told me. “That’s the only way you can become a changemaker that’s going to be valid enough to make a difference.”

As a former hustler (read: gambler, scammer, occasional thief) who made his money on the streets for decades (with brief stints in jail) before going straight and supplying the street’s most successful hustlers with custom finery, Day knows more about gaming the system than most. After all, this is a man who initially made his name knocking off the likes of Gucci, Fendi and Louis Vuitton. Now, they are his contemporaries.

“Did I think I might catch hell from the brands for co-opting their logos? Yeah, the thought crossed my mind,” he writes in Made in Harlem. “I was aware of the risks, but you gotta understand, I’m a gambler at heart. The whole time I was in business, I was rolling the dice.”

Some may counter that Gucci took a similar risk when they offered Day, who doesn’t even sew, his own atelier in 2017; but it’s a risk that has more than paid off. The luxury label is enjoying broader cultural relevance than it has in decades, in large part due to Day’s insistence that the label and couture experience be brought to his native Harlem, rather than exporting his talent and designs to Milan.

“If they were sincere, then I felt if they came to Harlem—the whole team came to Harlem—and expressed their sincerity, I think that’s a symbolic gesture, not only to myself but to my community; to let them know they came here and this is not a collaboration, this is not tokenism, this is a partnership,” he told me. “That’s why it was so very important for them to come.”

The comment could equally apply to Gucci’s recent cultural missteps‚ most infamously, the Leigh Bowery-inspired “blackface” sweater that sparked outrage among fashion lovers, celebrities and activists alike. Expressing his own disappointment, Day assured us that he would intervene—and once again, Gucci came to Harlem to make it right.

“You do have to make contact with the people who count the most, and the people who count the most are the grassroots people,” Day explained to me. “Because the influencers have the power, but they all fall subject to the grassroots people because they’re afraid to even express their differences about what the issue is for fear of losing their base, and that’s the most important thing. So, it’s on one end, understanding the dynamics of the industry, and on the other end, understanding the power of the grassroots. And in between that is the rest of everything.”

As a bridge of sorts between the two, Day says that he reads “every comment” written about him and his work with the label—and he’s not intimidated by those who cast him as a sellout due to his choice to dismantle fashion’s barriers from within. In fact, Gucci’s gaffe may have been a blessing in disguise, as already, Day’s response has resulted in the creation of a global changemakers initiative to address the lack of diversity in Gucci’s ranks (prompting several other labels to form their own), and black talent has already been placed in decision-making positions.

And, as Day noted during his talk, it would also be naïve to write off the ascension of Virgil Abloh at Louis Vuitton and the launch of Rihanna’s luxury line as mere coincidence. The success of Gucci’s partnership with Day is opening doors for the elevation of black talent throughout the luxury industry.

“One of my favorite stories is The Wizard of Oz. I went looking for the wizard and found him in myself,” Day told me, in reference to what appears to be his Midas touch. “I needed to have that inside of me, you know? I needed to reinforce that; I needed to feel sure of myself. ... that’s the armor; that’s the impenetrable armor.”

But for those expecting Made in Harlem to be a book about fashion, think again. Day’s is an intriguing and twisty tale about the hustle and the hustler, and it is eloquently and engagingly told, as the designer was also once an aspiring journalist. There is a profound vulnerability in Day’s story and a striking self-awareness as he recounts both his successes and failures as a man, father, son, brother, husband, and entrepreneur. In the end, Made in Harlem is, like him, an inspiration, which is what he told me he hopes young people, in particular, glean from it.

“The most important thing I want them to take away from this is never to give up—never to give up,” he said. “I know it’s already in them to make it, just as long as they never surrender.”

The Glow Up tip: Dapper Dan: Made in Harlem: A Memoir is available now at all major booksellers.