I love a good quest. As the resident comic-book and science-fiction guy at The Root, my pop culture life has been inspired by quests—Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, Lord of the Rings, Harold & Kumar Go to White Castle—if it requires finding hidden treasure or discovering a lost world, I’m all over it. Which is why this summer I set out on a quest to attend some of the biggest comic-book conventions in America, searching for the mythical Shangri-La of Blerddom.

Black nerd culture has become the hot new thing, with the success of movies like Black Panther and Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse and TV shows like Black Lightning. Dozens of think-pieces have been written in recent years about how changes in movies, video games and cosplay have finally given black folks a place in mainstream comic culture. But have things really changed? Have convention spaces really started to become more open and welcoming to black folks? I had to find out. Unlike the quests I grew up on, the world wasn’t at stake; half the population wasn’t going to be snapped and there was no imminent alien invasion. But it was still a journey where I learned a lot more about blackness than I expected.

“I never get this hype!” yelled one of my Morgan State University students as he hopped up and down to the beats of DJ-rapper Taylor Senpai. The ballroom of the Hyatt Regency Hotel in Crystal City, Va. was filled with hip-hop remixes of Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” classic Saturday morning cartoon theme songs and popular PlayStation games in mid-July. The first stop on the Black Nerd Quest was the third annual BlerdCon and I had brought along a group of my students to help take pictures and film the festivities.

Imagine a room full of black folks cosplaying as everything from Avatar: The Last Airbender characters to Erik Killmonger, swag surfing in unison. By the time gamer-rapper Sunn.zi hit the stage in her lime-green biker shorts and orange hair, the crowd was literally pulsating. If you’ve never heard somebody rhyme “centaur” with “hentai,” you’re missing quite the show (and if you don’t know what a centaur or hentai is, you need more black nerds in your life.) This whole menagerie of magical melanin was founded by Hilton George, who insisted that BlerdCon was for black nerds, not just nerds who happened to be black.

Hilton created BlerdCon as a way to fill the space that black fans of comics, video games and cosplay can’t find in other conventions. “People come up to me and say they’ve never seen this many black people, let alone black nerds, in one place,” he told me the first night, as we talked in a hotel suite overlooking the party downstairs.

By centering black entertainment, panelists and even black-owned food trucks, BlerdCon pushes back against the notion that somehow liking Pokemon and Star Trek is at odds with being authentically black. “[A white person] is never asked to give up their white card for being nerdy,” Hilton said—and neither should black people.

Hilton and I grew up in a generation where the only black nerd on television was Steve Urkel, and that guy had to create a whole new identity and play Sonic the Hedgehog for 20 years just to get his black card back. BlerdCon exists to let everyone know that you’re still black even if you can’t tell the difference between a Redshirt and “Red Bottoms.” It was almost if my quest began in the place where black folks would want to end up, protected and welcomed. At the same time, it made me wonder: If BlerdCon was such a heavenly place for black fans, just how bad were these other conventions?

If BlerdCon is the HBCU of comic conventions, then San Diego Comic-Con is the PWI that fools you by putting a bunch of smiling black kids on the website who you never see once you’re on campus. A week after dancing the night away to nerd rap, my Black Nerd Quest took me across the county to San Diego Comic-Con, the biggest, most elaborate comic book convention in the world. While BlerdCon has grown from 1,500 people in its first year to over 5,000 and filling up three hotels in year three, San Diego Comic-Con regularly has over 100,000 visitors from all over the world and features new trailers from major Disney, Warner Bros. and Fox superhero franchises, in addition to celebrity guests. (Even Sen. Cory Booker showed up at San Diego Comic-Con searching for the nerd vote.).

Demographically, San Diego Comic-Con is diverse, but at the same time, it’s not necessarily all that welcoming. The lines for panels, autographs, even getting to the merchandising hall are ridiculously long. Local San Diegans told me the convention has gotten more expensive, exclusive and corporate with 2019 being the worst yet.

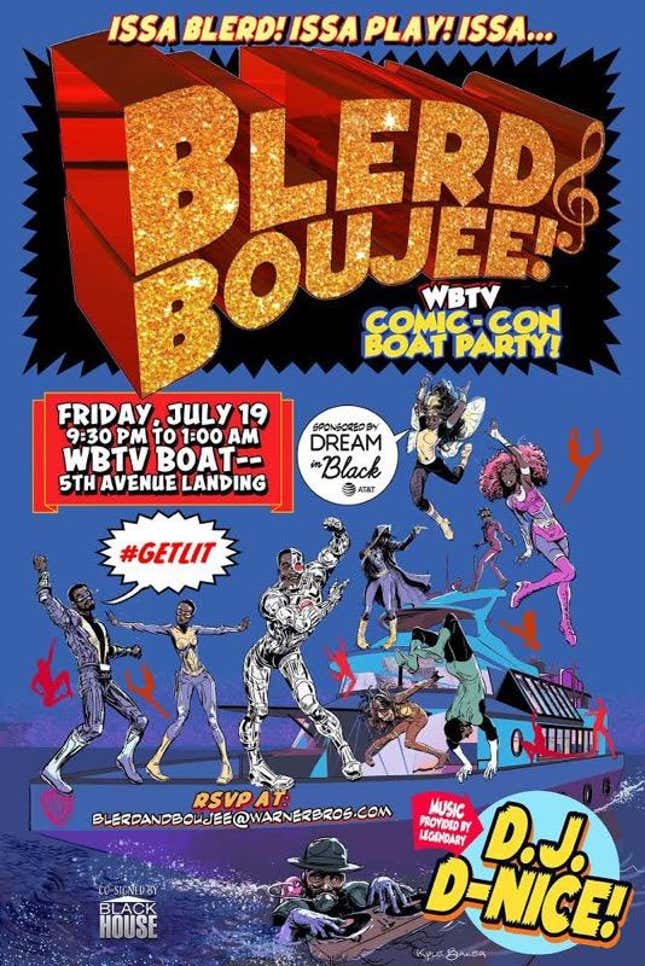

“I’ve been going for 15 years,” said a local videographer I spoke to “….And I left after about an hour this year.” While there were some black folks sprinkled throughout the convention here and there—you had high-profile panelists like Yvette Nicole Brown from Community, Angelique Roché from Marvel and Karama Horne from SyFy—they were few and far between. The holy grail of blackness for San Diego Comic-Con was a golden ticket to a party: The “Blerd and Boujee” yacht party thrown by Warner Bros. TV. It was a highly exclusive party for select members of the black press, black actors, producers and influencers in the genre. All San Diego Comic-Con parties are hard to get into, that’s part of the adventure of the weekend, and getting into Blerd & Boujee fell somewhere between the Mission Impossible break in and getting past Gandalf the Grey, but it was worth it.

The Blerd and Boujee party was like being a plus-one for a dinner party at the Batcave if it was produced by Diddy. Every black celebrity actor (and some white ones, of course) or producer in genre television was there: Cress Williams (Black Lightning), China McClain (Black Lightning, The Descendants), Mike Colter (Luke Cage), Jessie Usher (Independence Day 2, Shaft, The Boys), Freema Ageyman (Doctor Who, Sense8). If you’ve seen a black person in a show with aliens, laser or heroes in the last five years, they were at this party.

I even ran into Jamil Smith from Rolling Stone and writer Evan Narcisse, formerly of our sister site, io9. For such a high-profile guest list the vibe on the boat was incredibly comfortable; people seemed legitimately excited to meet actors from shows they admired. While San Diego Comic-Con itself didn’t provide many safe spaces for black folks, on the Blerd and Boujee yacht, people felt free to discuss everything from the racism of fans and the boundaries they faced in the industry to the fun of living out their childhood fantasies, all while DJ D-Nice spun old-school hits in the background. So while there were black cosplay events and some side experiences at Comic-Con, the truest place to find elusive blerd-dom was probably the most exclusive party of the entire weekend.

The final leg of the quest was flying cross-country again to America’s fastest-growing Chocolate City, Atlanta, for the biggest comic convention in the South (about 80,000 visitors), DragonCon. I had been to DragonCon before, usually meeting up there with friends from college, but never after going to both BlerdCon and San Diego Comic-Con. If BlerdCon was the proverbial black cookout, and San Diego Comic-Con was the fancy work banquet where you befriended the black serving staff and they snuck you some Lawry’s and hot sauce for your tilapia, then DragonCon was the gentrifying restaurant that knows they have a large black clientele and do their best to serve everybody. It was a worthy endpoint for my quest.

DragonCon certainly doesn’t have the kind of focus on black fans as BlerdCon but did manage to score some high-level guests, like voice actress Kimberly Brooks (Voltron, Steven Universe, Doc McStuffins) and actors from Black Lightning, which films in the city. What really distinguishes this con, though, is how much the local black community is invited and embraced; you see hundreds of families at the cosplay parade down Peachtree Street. Add fashion students from the Savannah School of Art and Design and the fact that it was Black Pride weekend, and you saw more open participation across black life at the con; you even found it in the most unlikely of places.

“What are you looking for?” Asked a skinny, bald white guy at a comic booth.

“Black stuff,” said my friend Marcus, who had never been to a comic convention but accompanied me on my quest to buy comic nerd merchandise on a Saturday afternoon.

Turns out the white guy’s name was Ted Sikora and he published a comic called Tap Dance Killer about a black theater actress in Cleveland who gets so wrapped up in a role she develops a split personality that fights crime. Ted’s inspiration? He’s married to a black woman and wanted his daughter to have comic characters that she could aspire to. (I’m assuming that doesn’t include the serial killer part).

Then we talked to Chuck Brown and Sanford Greene, creators of Bitter Root, a steampunk fantasy comic about a family of black demon busters that just got acquired as a film project for Legendary Pictures. (I highly recommend the book; I used it in my comics class at Morgan State). By the time I was about to buy a Funko Pop! of Axel Foley for a friend of mine SIGNED by Eddie Murphy, (who was in town filming Coming 2 America), I had probably spent somewhere close to grad school rent on pieces of paper and plastic representing various forms of black popular culture. Of course, that’s part of the joy of conventions and quests: recapturing an idealized vision of blackness on paper, on film or in plastic that you can take with you. Because if you aren’t coming up with the stories yourself, you can at least keep a piece of them. And as a black person, keeping anything, especially your culture, is kind of an event in and of itself.

“This whole thing should be so much blacker,” Marcus said as we recapped the weekend. “I mean, we’re in Atlanta. I didn’t see anybody dressed up as MLK or Coretta,” he continued.

“Yeah but they aren’t like REAL superheroes,” I argued.

He paused for a minute...

“I disagree!”

This exchange in many ways epitomizes my entire journey over the summer. I went out in search of blackness in nerd spaces and found that, in some ways, things have gotten better. Black folks are telling the comic world who their heroes are, and creating spaces where that can happen, even in places where they didn’t exist; whether that’s in the form of parties, massive cosplay photos or even just getting art into the room that wasn’t open to you just a few years ago.

At the same time, unless it’s run by black folks, the convention structure itself continues to marginalize so much of black culture and talent, even as the fan-base grows in power and influence. Previous attempts to harness the power of black fans have had mixed success. WakandaCon kinda fizzled in its second year and UniversalFanCon was the Fyre Festival of conventions, so it’s crucial that this kind of guerrilla blerdness in existing cons continues to grow.

Many science fiction and fantasy quests end on some after-school special twist; the hero finds out “the true power was in you all along”—or even better, “the real treasure….was the friends you met along the way.” To that end, I learned that searching for a black nerd space didn’t matter, since black folks, whether only a few of us at a convention or a black lady courtroom, will always find a way to celebrate each other. It’s just that now, perhaps for the first time in cultural history, we do it in costumes as our own heroes.