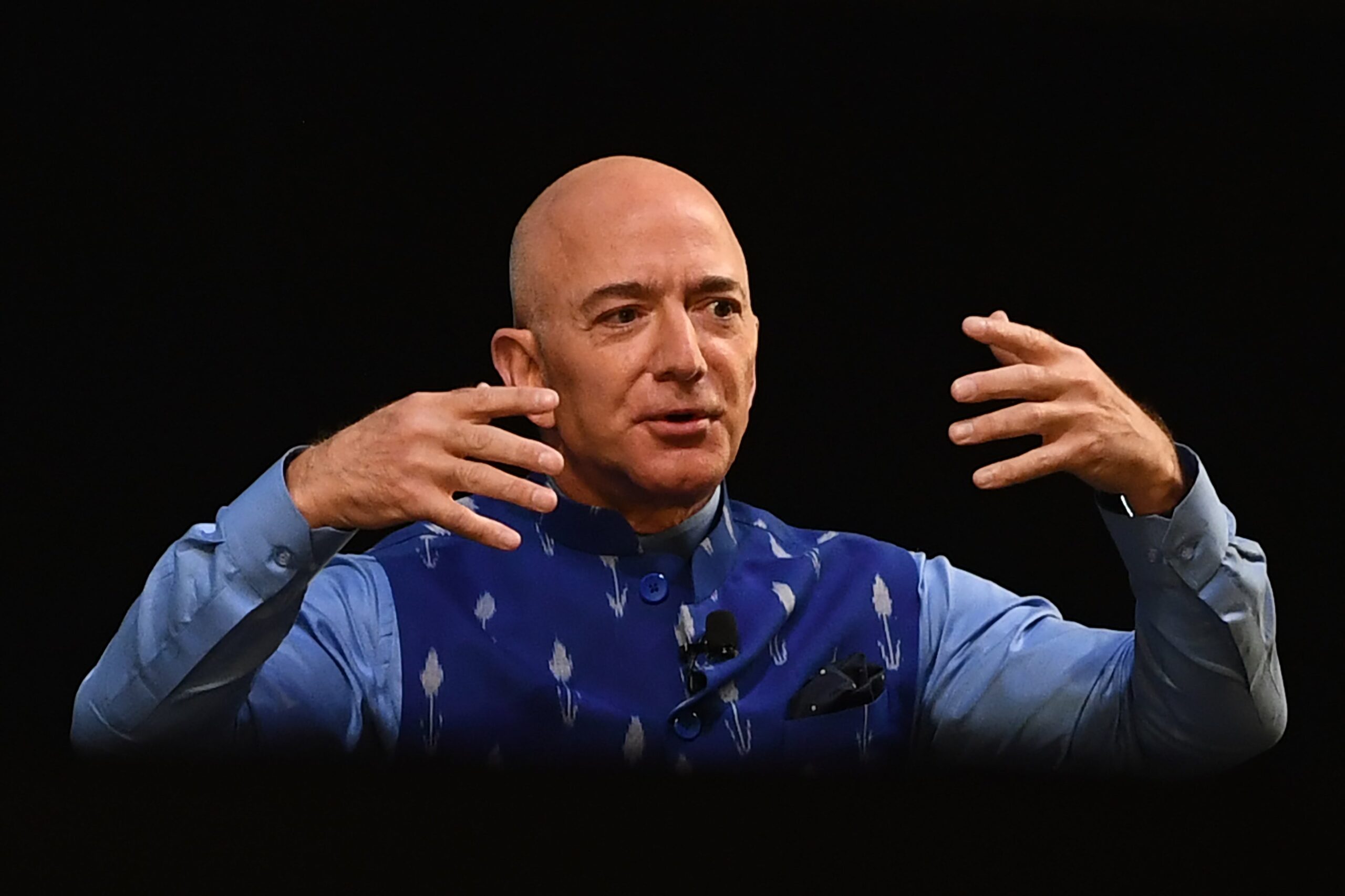

If you look at allyship as some sort of contest, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos has been eager to put some points on the board. He’s done this mostly through highly publicized, “spicy” responses to racist customers, and by canceling his meetings on Juneteenth and encouraging other employees “to do the same if you can.”

Suggested Reading

But Amazon’s black workers say Bezos’ record on addressing racial issues at his company leaves a lot to be desired, according to a new report from The New York Times. Bezos’ Juneteenth email provides a prime example: as the richest man in the world urged his employees to reflect on systemic racism, his black employees—many of whom work at Amazon’s fulfillment facilities—couldn’t simply clear their schedules that day. And unlike other major retailers like Target and Nike, Amazon didn’t offer Juneteenth as a company-wide, paid holiday.

But the issues with Amazon go much deeper than paid holidays. For example, Amazon has been hostile to efforts to unionize—and Black employees, particularly Somali immigrants in the company’s Minneapolis warehouses—have been instrumental in this effort. The fact that fair labor practices could be a racial justice issue seems to elude Amazon’s senior management.

In fact, as the Times points out, employees have directly flagged Amazon’s problems with racial inequality and bias directly to Bezos and other members of his senior team:

In April, before George Floyd was killed in police custody in Minneapolis, a group of midlevel employees wrote to Mr. Bezos and his senior team, saying there was “a systemic pattern of racial bias that permeates Amazon,” according to emails viewed by The New York Times. They said they were prompted to write after a leak of meeting notes showed that David Zapolsky, Amazon’s general counsel, had called a black warehouse employee in Staten Island “not smart or articulate.”

Mr. Zapolsky had said his comments were “personal and emotional” and that he did not know the employee was black. But in their email, the corporate employees said it “was not an isolated incident, but rather a symptom of a bigger problem.”

They said Amazon adopted the entrenched racism that plagued America, evidenced by the “homogeneity” of the its leadership compared with “the rich racial and ethnic diversity amongst our hourly worker population.”

One example of Amazon failing to respond to the concerns and needs of Black employees involves racist graffiti that has been scrawled into the bathrooms of its Los Angeles warehouse since last year. Johnnie Corina, who filed a discrimination complaint against Amazon last week, said he reported the hate speech several times to the company, but to his knowledge Amazon never launched an investigation into the incidents. Nor did the company address the graffiti with workers, or say the behavior was unacceptable (Amazon denies this, saying it addressed warehouse employees about “unacceptable graffiti” in December and February and began investigating the hate speech in June, perhaps after reflecting on the importance of Juneteenth or something).

As a result of the company’s inaction, Corina said he didn’t feel safe going back to work.

“To not do any interventions is really not a safe environment for a black person,” he told the Times.

Whatever energy Amazon lacked in addressing racist hate speech, it more than made up for it in firing a black janitorial contractor who shared images of the graffiti on social media. Donald Archie, who worked at the same LA warehouse as Corina, recently filed a complaint against the company for terminating him after he posted a photo of the racist words on Twitter.

Yes, you read that right. He wasn’t fired because Amazon thought he was responsible for the graffiti, but because he called it out.

Amazon’s response? Archie was fired for “not escalating concerns about the graffiti and violating the company’s cellphone use policy,” the Times writes.

Sounds like you’ve got some meetings on your horizon, Jeff.

Straight From

Sign up for our free daily newsletter.