What is black music? For many, it’s soul, funk, R&B, hip-hop and essentially all genres of music that reflect roots in blackness. But the industry doesn’t hear us. Music is very much a culture of “We make it, they take it.” We’ve seen it throughout history in the theft of everything we exclusively create within music, from Elvis Presley to Justin Timberlake.

Did you know that there’s a such thing as Black Music Month, or African-American Music Appreciation Month? Well, there is. There’s a month for everything now; seriously. Okra has a month, which also happens to be June, but okra definitely doesn’t deserve it. The smile—that thing on your face when you’re happy—that has a month, too; well, two, kinda, since it goes from mid-May through mid-June. Impressive.

But yes, black music has a month. But what is black music?

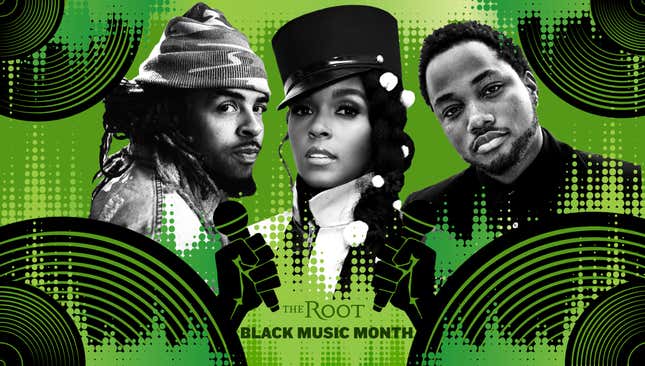

To Janelle Monáe, there is no definition. You can tell in the way she moves as an artist. It’s not only her own beat, but it’s her own drum, too. To New Orleans teacher-turned-rapper Dee-1, it’s steeped in his Southern roots. For Leon Thomas, black music is limitless; and as an actor and a performer, Thomas has high hopes of being able to cross mediums effortlessly. “You can do both and chase what you want to get done,” Thomas says.

You know Monáe. You may know Dee-1. He’s the viral rapper that gave us the most relatable lyrics about Sallie Mae. And if you watch Insecure, you’ve seen Thomas as Issa’s jump-off neighbor who caught our girl slippin’. These three artists have some things in common: They’re black and they make music. They take special care in penning much of their music and also have their hands in production. Being an artist and having a hand in the construction of your music means giving it a special care that connects you to the soul of the music. That’s why black music is so important—it’s more than a sound; it’s our souls.

The Root: What is black music? Does it have a sound?

Janelle Monáe: [It’s] undefinable. I think that it is absolutely impossible to speak about the many kinds of sounds we’ve developed in the past, we continue to develop right now in the present and we will continue to develop in the future. We’re innovators and we have been at the root of inventing genres, which I really don’t believe in. I don’t love labels or the ideas of having labels on music. It takes the fun out of evolving the sound, in my opinion.

But I do know that we have had rock ’n’ roll pioneers who have been at the forefront of rock ’n’ roll, never receiving that credit. You think about Little Richard, you think about people like Jimi Hendrix, and I can go on. Sister Rosetta Tharpe, I just think that what we have is and has always been magical and very special and un-fuck-with-able.

We’ve been the well; the music that we put out has been the well that so many other people have drank from and may have even profited more from us and gained more from. However, we do music because it’s in us; it’s in our heart and it’s one of the only things that keeps us at peace in a world that constantly tries to tell us that we don’t matter as much.

Leon Thomas: I think black music is such an important part of culture. You’ve seen from jazz to the blues, even through our influence throughout the gospel genre, and of course hip-hop, that we’re true creators. And I think the constant you can find is the soul of music; black people bring the soul of music no matter what arena or genre we’re in. I think we’ll continue to create genres and continue to blend sounds and push the limits of innovation.

Dee-1: To me, it’s just music made by black people. [Laughs.] It’s not diluted or infiltrated with other influences. I don’t really know how to define it.

TR: How did you decide music was for you?

LT: My mom is a singer and my stepdad is a guitarist. He played for B.B. King and Salt-N-Pepa, Hi-Five, a new jack swing band back in the day. They also ran the independent label out of our house and had a club-date band, so I was a backstage kid always. My grandpa was also a Broadway actor and opera singer as well. So I come from a lineage of music and very well-respected musicians.

TR: What has been your most iconic career moment at this point?

JM: I’m so scared to even say that. I mean, I honestly feel like I’m just getting started. There’s more to come. It’s a journey that I’m not trying to hurry up and make it to the top with. I’m fine with the speed bumps, the slow night walks of the journey, the setbacks, the setups.

It’s really about the journey for me and never resting on my laurels and never feeling like I’ve arrived. I think that’s a dangerous disposition to have.

TR: Do you think that black artists get the respect they deserve?

JM: The limitations that I feel like have been put on black women in music in particular are deeply bothersome and frustrating. When I see artists like Kimberly Nicole or Dawn Richards or Sneaks—or we can go from Lauryn Hill to Kelis to Missy to Esperanza Spalding to Lizzo, and so on and so forth—we can do it all. There’s nothing we can’t do, yet labels like R&B, which—I have no problem with rhythm and blues; I love R&B music, even though I hate putting labels on music. I’m aware of what folks consider R&B music, but I hate that we can’t be free in the way that we approach music and get mainstream acceptance. It ... always [has] to be, like, a subgenre or experimental R&B.

We do have it harder when it’s time to get to get our music pushed on mainstream airwaves, especially when we’re doing music that’s outside of what the gatekeepers think is black enough. That’s a real thing, but we will continue. I don’t let this stop me, and it doesn’t stop any of the artists that I named.

I think that with the internet and with technology advancing, there will come a time where black women in music will reign supreme, even more than they already are, and I think that having the stamp of approval from my peers, especially black women, means more to me than any accolade, any reward. That’s enough for me. It’s enough for me to have the support of black women and especially artistic black women.

LT: I came from a very white side of the industry, dealing with Viacom and Nickelodeon early on. I was one of the only black actors on the network for a while, and sometimes on set, you’d get the “Hey, brother!” with this super-complicated handshake, and all I was going for was a traditional one. Or, “Hey, what’s up, my guy!” and they say hello to everyone else and go into Ebonics for me. It’s a nonissue for me. I nip it in the bud on first sight.

D1: I’m a rapper. So in terms of speaking, I think that we at this point as black artists, we’re sought after. People want what we have. Now, in terms of how they try to exploit what we have, that’s one of the challenges. I think that people desire what we have in the talent that we bring to the table; people really want that.

Capitalism, not racism, makes it to where the music industry itself is quick to say, “Yeah, we’ll use you for your talent and turn it into this caricature or just this clown,” and use it for whatever purpose they have designed it for and do away with you and suck all the talent out of you.

I think that happens to black artists and white artists in the music industry. The love of money and the power of greed makes it to where a black person would exploit another black or is just as quick as a white person [to] exploit a black artist.

LT: I feel like it’s definitely a situational thing. Human beings respect people who respect themselves. And what we’re seeing right now is a great increase in unapologetic creators, people who innovate, people who color outside the lines and kind of break the walls. I think those who kind of play it safe sometimes may not be as respected; they may be enjoyed. But I think the test of time will tell that those who are really pushing the boundaries forward are going to be here for another 20 years.

I think there are certain boxes that can be put in front of the black artist, and it’s really your choice to either climb ... in that box or find ways to break the barriers and create something different. I think that’s what separates those who are around for more than 10 years. People like Stevie Wonder continue to perform and, you know, be beloved in society. He had to let his sound evolve probably three or four times throughout his career.

Check out Dee-1's latest, “I Don’t Want to Let You Down” here.

Check out Janelle Monáe’s latest, a visual album and emotional picture, Dirty Computer here.

Check out Leon Thomas’ latest, “Favorite” here.