I feel rich and I like being seen as rich. So am I rich? Is that how this works?

Maybe it was because my eyeballs have never rolled to the white meat so many times, rendering me unable to use them to read? Or maybe it was the countless explanations of the black experience by someone who is very clearly white? Whatever it was, I tried. I honestly gave it my best effort, but I could not, for the life of me, finish Rachel Dolezal’s—I mean Nkechi Amare Diallo’s, but mostly I mean Nbecki’s—debut memoir, In Full Color.

I volunteered myself to be the one to read the book as an assignment, partly because I was curious about what this woman could possibly share with the world (that she hasn’t already) at length. Also, I figured I’d be able to leverage this horrible assignment throughout the year for bonus personal or vacation days or any other favor my managing editor, Danielle Belton, would throw my way.

Yeah, I’m not a martyr—although after making it 157 pages into (two pages before the photo insert) the 277-page book by Nbecki, I feel like death.

I went to Barnes & Noble to pick up the book (don’t worry, I was reimbursed). When I sat the book on the counter to pay for it, the older black woman checking me out picked it up, looked at me, looked at the book again and put it down.

“It’s for work,” I said, trying to justify why I’d make such a purchase.

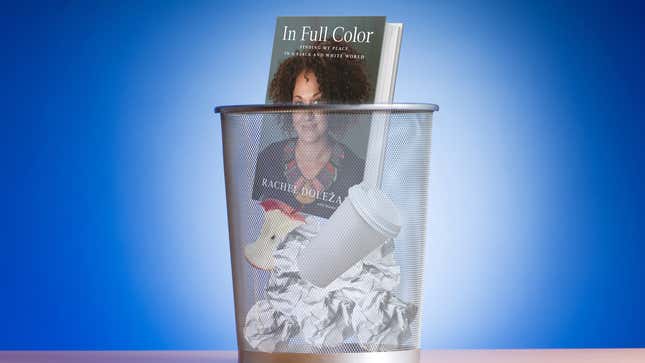

She laughed. I paid and left, feeling like I’d done a bad thing. Almost immediately, I took the book sleeve off. I read a lot in public, and I couldn’t have people seeing Nbecki in all her curly-wig glory on the cover.

The foreword was written by Albert Wilkerson Jr., a black man whom Nbecki adopted as a father figure. He lost me when he compared her to some of the biggest black civil rights leaders ever. He wrote: “I also came to appreciate others—Frederick Douglass, Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and my father Albert Wilkerson Sr., to name a few—who, by their example and by the power of their convictions, fought racial bias and prejudice. Rachel Dolezal is also such a person.”

Sir. Absolutely not. This is not going to be fun, I thought. I will give Nbecki a sliver of credit: Because of her affinity for blackness, she often attempted to champion it. She learned black history ferociously and couldn’t help being mesmerized by Africa’s kings and queens. But that’s where the sliver starts and stops.

All of her “Say it loud” became null and void when she also proclaimed “I’m black and I’m proud” and essentially made a mockery of the very ethnicity she coveted. In In Full Color, Nbecki grasps at straws, victimizes herself and even attempts to put some mustard seed of blackness into her upbringing. She said, “[M]y hair at birth was almost black and my skin was much darker than my parents’ ... ” *Rolls eyes to the white meat.*

She claims that as a child growing up in rural Montana, she dreamed of being a Bantu princess. This was way before the internet, and she was raised by (to let her tell it) strict Bible-thumping, abusive and sheltering (not in a nurturing way) parents. How would a young and very white Rachel know anything about an African princess?

“I would pretend to be a dark-skinned princess in the Sahara Desert or one of the Bantu women living in the Congo,” Nbecki wrote. “Imagining I was a different person living in a different place was one of the few ways … that I could escape the oppressive environment I was raised in.”

She claims this was always in her heart, and even includes a photo of a self-portrait she drew when she was a child. The child in the crayon-colored portrait was dark brown with yellow and black lines squiggling out of her head, representing how she wanted her hair to look, or how she saw her hair.

“I grew up in a painfully white world, one I was happy to escape from,” Nbecki recalled of her childhood.

At one point, Nbecki compared her childhood to slavery. Yes, slavery:

[I]t wouldn’t have been too much of a stretch to call me an indentured servant.

Like many of us, she had her fair share of chores while growing up. Nbecki said that because of the strenuous chores she had to endure, she was just like black folks who suffered through chattel slavery. She claims to have begun making crafts for money to pay for the things she needed because her parents wouldn’t provide.

The more I read, the more I realized what she was trying to do. Nbecki wanted to make herself look pitiful, like the biggest victim of growing up white we’ve ever seen. That way, her morphing into blackness would be accepted or at least not so vehemently rejected.

The sad thing is, if this is the truth, Nbecki’s upbringing is upsetting. She talks in detail about being molested by her brother, being force-fed to clear her plate, even if she vomited, and having her father flirt with her. But there’s just something about Nbecki that gives you “the boy who cried wolf” vibes, and believing her is a challenge.

Perhaps it’s because we met Rachel Dolezal as a white woman leading the Spokane, Wash., NAACP chapter, denying her whiteness? In the book, Nbecki claims that the reporter who asked her on that fateful day whether she was black robbed her of her moment to come out as black on her own terms.

Once again, sir, no. Absolutely not. Not like this. This isn’t sexuality. This isn’t a story of pride that she gets to tell her grandkids one day. This is ethnicity. And we don’t get to choose. It’s given to us.

Yes, you can have your preferences, which Nbecki made very clear. When she moved out of Washington to go to college, her preference was kente cloth, box braids and tanned skin—a caricature of the culture she so admired. She blurred her appreciation straight into appropriation. Her brand of being black was also a costume:

I started wearing my hair in Poetic Justice box braids, sporting dashikis and African-patterned dresses.

I gave it a valiant effort, but after repeated exposure to Nbecki’s justification of her quest for blackness with a traumatic childhood and a violent marriage to a black man who wanted her to be the whitest woman she could be; Nbecki’s various history lessons about black hair and black men dealing with police; Nbecki’s occasional explanation of appropriation (and how she’s not doing that); and, not to mention, again, when she compared her childhood to indentured servitude—I had to permanently put In Full Color down.

I didn’t even make it the the pictures, but I flipped through them. They were just more “proof” of Nbecki’s blackness: images of her adopted brothers and sisters, her black son, her black friends, her various black hairstyles. It was as if she was saying, “Here, take a break from my exhausting words and look at my black pictures!” Jesse Jackson and Marilyn Mosby are even in there!

There’s no real reason to read this book, and I do regret pitching the assignment. Her 15 minutes of fame were up long before they started, and this book is trying to extend her moment in the sun. But honestly, it’s curtains for this sideshow. Don’t read the book. I know you won’t, but I felt that it was my duty to at least insist.

Check out my attempt at reading In Full Color in tweets—some complete with epic GIFs.