For over 50 years, Drs. Haki R. Madhubuti and Safisha Madhubuti have been building together alongside a community that reads like a who’s who of the Black Arts Movement. Their half-decade together has included raising a successful blended family and launching numerous independent African-centered institutions in Chicago—where in 1967, poet, cultural critic and editor-publisher Haki (birth name, Don L. Lee), launched Third World Press, now the largest independent Black-owned publishing press in the United States.

He met his future wife only a year later, while visiting the high school where Safisha was teaching summer school while completing a master’s degree in English at the University of Chicago.

“My master’s thesis was on the Black Arts Movement and included attention to Haki’s poetry,” Safisha explains. “Haki had been invited by the principal—Barbara A. Sizemore—to speak at the school. We met. He asked for my phone number. And so began our relationship.

“I always point out that mine was not the only number he asked for,” she coyly adds. However, he likes to respond that I was the one he called...But I know differently.”

Perhaps, but Haki was undeniably struck by the “beautiful, conscious and highly intelligent” Safisha, telling The Root: “I realized very quickly that I missed her in between my travels between Chicago and Washington, DC while I was working at Howard University and traveling to speak around the country and around the world.” That, coupled with their “shared interests in literature, in Black culture and history, and in community building,” made for a strong attraction, as Safisha explains.

“He was tall and handsome. He read vociferously. In his apartment, he even had books in his bathroom,” she recalls, noting that Haki still owns at least 10,000 books. “So I saw him as someone who was intellectually curious. He had [and still] has an enticing personality. He draws people to him and always finds ways to bring you into projects he has imagined.”

Those projects consistently came to fruition, growing in tandem with the couple’s bond.

“From the very beginning of our relationship, we began to build institutions, first with the Institute of Positive Education (IPE),” explains Safisha. “IPE included a cohort of culturally conscious and dedicated men and women. We operated in many ways as an extended family. We published materials that we felt informed our community about salient issues. We hosted community gatherings and community lectures in which members of the community would gather to discuss, debate and plan work that needed to be done in our community. We had a food co-op and a farm.

“And finally by 1972, we started our first school, New Concept School, as a Saturday program,” she continues. “Parents in the Saturday program asked us to expand to a full-time operation, and so in 1974, we opened full-time. I had been working in the community college system in Chicago—and then, to my mother’s dismay, I quit my job at the community college to direct and teach in the school we founded.

“Haki and I worked closely together, with our colleagues, and in so doing developed a bond; a bond based on deep friendship and respect for one another. The romance evolved out of that friendship bonding,” she adds. Many families began and grew out of our collective work together.”

Ready to build her own family, Safisha at last drew a line in the sand with Haki, already a father of three.

“Haki likes to say I proposed. Not the case,” she explains. “We had been dating for five years. I decided at that point that it was contradictory for us to be talking about and promoting the idea of family [when] we had not made that commitment to one another. And so, I wrote him a letter in which I described the contradictions between what we said and what we did in terms of our relationship. And I essentially told him to put up or shut up,” she says with a smile, “and that I would remain dedicated to the work we were doing in building these institutions, but I would not maintain our romantic relationship in the absence of marriage. And in his wisdom, he agreed.”

Haki admits he had a little nudge in the right direction—from an even wiser source. “I shared the content of the letter with [Pulitzer Prize-winning poet] Gwendolyn Brooks. She told me not to make the biggest mistake of my life and not marry Safisha. She was my cultural mother and that sealed it for me.”

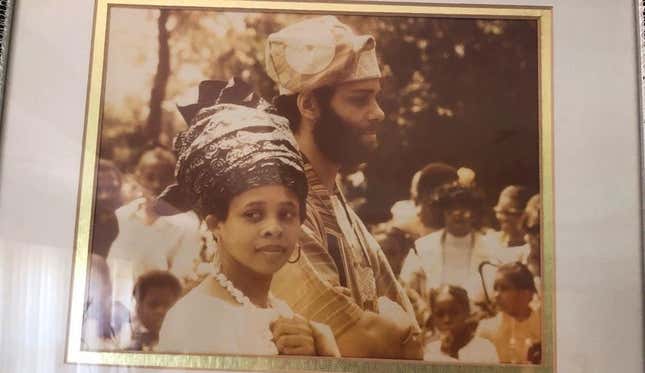

The two married in June of 1974 in a Chicago public park, foregoing the typical trappings of a white wedding for an African-centered ceremony in keeping with IPE’s community-based tradition. The ceremony was conducted by one of its members, writer Jabari Mahiri (now a professor at the University of California, Berkeley), while the couple’s legal license was signed by renowned Black Arts Movement artist Murry DePillars. In place of an extravagant white gown, Safisha wore a traditional West African gele and lappa, paired with a handmade white blouse.

Their reception took place in the two large connected storefronts they’d recently purchased to house the institute. “We had only begun preliminary renovations...The walls were not in good shape, and so we simply posted African fabric on the wall,” Safisha recalls. “It was the first time my mother ever wore African dress, but she did for the wedding...It was a community event in which all members of the IPE community participated.”

Celebrating 47 years of marriage this month, the Madhubuti family has grown to a total of six children now ranging in age from 41 to 57. Haki’s children Shabaka, Regina and Mariama have since been joined by Laini (who, along with her fiancée Reese, kicked off The Root’s “How We Do” series), Bomani, and Akili, as have nine grandchildren ranging from age three to their thirties.

“They are a wonderful cohort,” says Safisha. “They are all very close to one another and together do much to keep the family together.”

“My greatest challenge was to build a family because I did not come from a stable family,” Haki shares. “It was an ongoing learning challenge for me to build a family that we both could be proud of, considering my own challenges as a child.” He gives his “extremely intelligent, children-centered” wife ample credit, adding: “We are compatible at every level.”

“I think we have played complementary roles in raising our extended family,” Safisha agrees. “He tends to be the point person for accountability and teaching what it means to be responsible. I, on the other hand, I think have played the major role around social and emotional wellbeing and education.”

The couple’s social and educational impact has also grown outside the family, as well. In addition to Third World Press and Third World Press Foundation, IPE and the New Concept School, the Madhubutis launched the African-centered Betty Shabazz International Charter Schools in 1998, one of which is named for the “important and powerful mentor” who facilitated their meeting, educator and former board member Barbara A. Sizemore. They agree none of it would’ve been possible without their community supporting them through inevitable “challenges but also opportunities [of] learning how to make a living to support our family, sustain these independent institutions, raise our family, and navigate these multiple commitments—and at the same time, finding time for one another.”

In addition to Sizemore and Gwendolyn Brooks, Haki credits editor Hoyt W. Fuller and poet Dudley Randall, both Black Arts Movement pioneers, as his advisors, “themselves being powerful examples of what it means to be a Black man.” He also considers Safisha’s mother a vital influence in their success as a couple.

“My mother came to live with us when I started graduate school working on my Ph.D. at the University of Chicago. She left her home and ended up living with us for over 30 years until her passing,” Safisha explains. “When I left my job at the city college, Mother said that man [Haki] had put the hoodoo on me and she went to her pastor and asked if he could find a psychologist to help me out. However, over the 30-plus years she lived with us, she and Haki became mother and another of her sons,” she continues. “She loved him dearly. My mother was a take-no-prisoners person...but she was certainly my anchor for navigating challenge.”

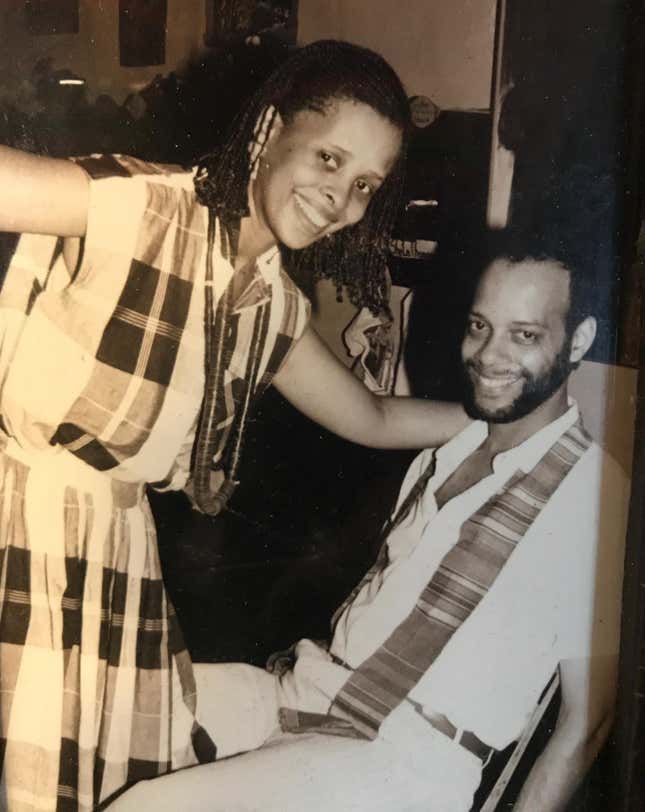

Both now retired professors, Safisha, aged 75, and Haki, now 79, are navigating new issues together. “We are wrestling with what it means to age and how our needs [have changed] and how we imagine what it will be like going forward,” they write via email. “Staying healthy. Figuring out how to pass on the torch of leadership for the institutions we have founded. Following our grandchildren—both the adults and the young children—to understand their unfolding.”

“Romance at 75 and 79 is not the same as at 35 and 39,” they add. “Friendship is abiding and is the foundation.”

“I think because we had been together for five years before marrying, I knew him well,” Safisha notes. “As with most couples, I could not anticipate what challenges marriage, living together, and raising children would bring. However, a commitment to the relationship, to each other, and to our family has sustained us for these 50-plus years. I always say to couples, before you marry—making that personal, spiritual and legal commitment—you should recognize what you don’t like about the other person, but know you love them in spite of that. Marriage does not change people.

“You have to talk to each other in order to resolve any conflicts before they blow up and become too large to solve,” Haki adds.

“There is no foolproof way of navigating conflict or tension. But bottom line, I think you have to respect the other person. You have to create ways of being together that respect your differences,” Safisha continues. “You have to understand that you can’t transform that person into a version of him or herself that you want. And you have to be honest with one another, knowing that your mutual respect and love for one another can indeed sustain you through challenge.”

Over 50 years after first meeting, the Madhubutis are still bound by the same qualities that initially attracted them to each other. “My most favorite quality in Haki is his intellective breadth,” Safisha says. “He buys me books. He introduces me to new ideas. The other quality I appreciate is, of course, his dedication to family and to community and the fact that when faced with challenges—family-related or community-based—he always takes the position that failure is not an option.”

“Message not confidential, but to brothers writ large,” Haki adds with a wink: “Marry partners smarter than you—and occasionally let them know it.”

You can read prior installments of “How We Do” here.