When I was a kid, I didn’t live close enough to a comic book shop to get there on my bike. My parents would have to take me to Fair Oaks Mall in Fairfax, Va., and I’d get my comics off the old spinner racks at Waldenbooks. As the years went on and specialty comic shops opened, my friends and I had a comic book ritual of sorts.

Matt, Jeff and I would borrow one of our parents’ cars, drive out to our favorite comic shop, then go to Jeff’s room and read comics until we had to go home. Stacks of X-Men, Captain America and Spider-Man comics would be spread out all over the floor.

This is how I spent my ’90s childhood.

And while at the time the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday was still up for debate, Al Sharpton was considered controversial and Public Enemy wasn’t played on “mainstream” radio–in a strange way all of that comic reading gave me a racial and political education that my lily-white suburban Virginia life never did. And it’s all thanks to Stan Lee, the creative and driving force behind Marvel comics for half a century, who passed away Monday at the tender age of 95. He gave a black kid a place to play in the cosmos and beyond, and the world is a little less bright after his passing.

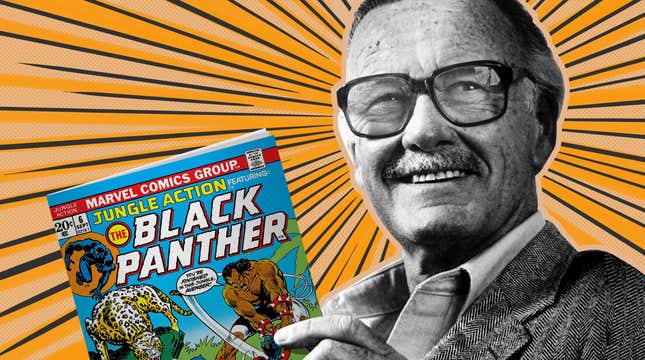

Over the next 24 hours you’ll hear how Stan Lee is credited with creating Daredevil, Thor, Iron Man, Ant-Man, Dr. Strange, the Wasp, the Hulk the Avengers, the Fantastic Four, Spider-Man and, of course, Black Panther. What you won’t hear as much is how he was screaming from the rafters about racism and discrimination while providing a curriculum for black kids like myself when public schools and all other forms of pop culture summarily shut us out.

Stan Lee didn’t just develop the modern superhero, he brought activist heroes and storylines to the mainstream when most other white publishers let alone newspapers were still playing footsie with Nazis, terrorists and bigots.

It is hard to overstate how important Lee is to black kids growing up in the 1980s and ’90s back when comic books were considered a “white” thing. I have literally teared up a few times while writing and thinking about how much joy he brought to youngsters like me, and how much his passion and excitement for comic books helped validate this hobby and the culture that goes with the genre. More than any other golden age comic creator Lee’s characters put blackness and the black experience at the forefront.

When Lee created the X-Men in 1963, the battle between Magneto and Professor X was meant to be a rough allegory for the integrationist vs. nationalist philosophies of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. Yes, the idea of black oppression and philosophy being played out by mostly protestant white guys like Cyclops and Ice-Man is problematic in hindsight (Magneto is Jewish), but it was a radical idea at the time. It also laid the groundwork for a comic that always spoke to racial injustice, even to kids like me who loved comics but seldom saw themselves in the stories and shows of the genre.

By the ’90s, the ideas Stan Lee established had evolved, and I was spending my Saturday afternoons reading about Genosha, the apartheid state that forced mutants into labor for regular (read: white) humans. When my class wasn’t talking about apartheid, I was learning it from Stan Lee’s creations. Lee’s creations seamlessly integrated “blackness” into comics in a way that was revolutionary and organic all at the same time.

Peter Parker was a poor, white kid who was mentored by his black editor at the Daily Bugle newspaper, Robbie Robertson. Captain America’s best friend was the Falcon (played by Anthony Mackie in the movies) who wore technologically advanced wings built by Black Panther (in the comics). Black Panther was the king of a super technologically advanced, never-conquered, African nation called Wakanda that introduced me to afro-futurism before I even knew what afro-futurism was. Stan Lee created all of those black characters, from kings to sidekicks; from father figures to managers.

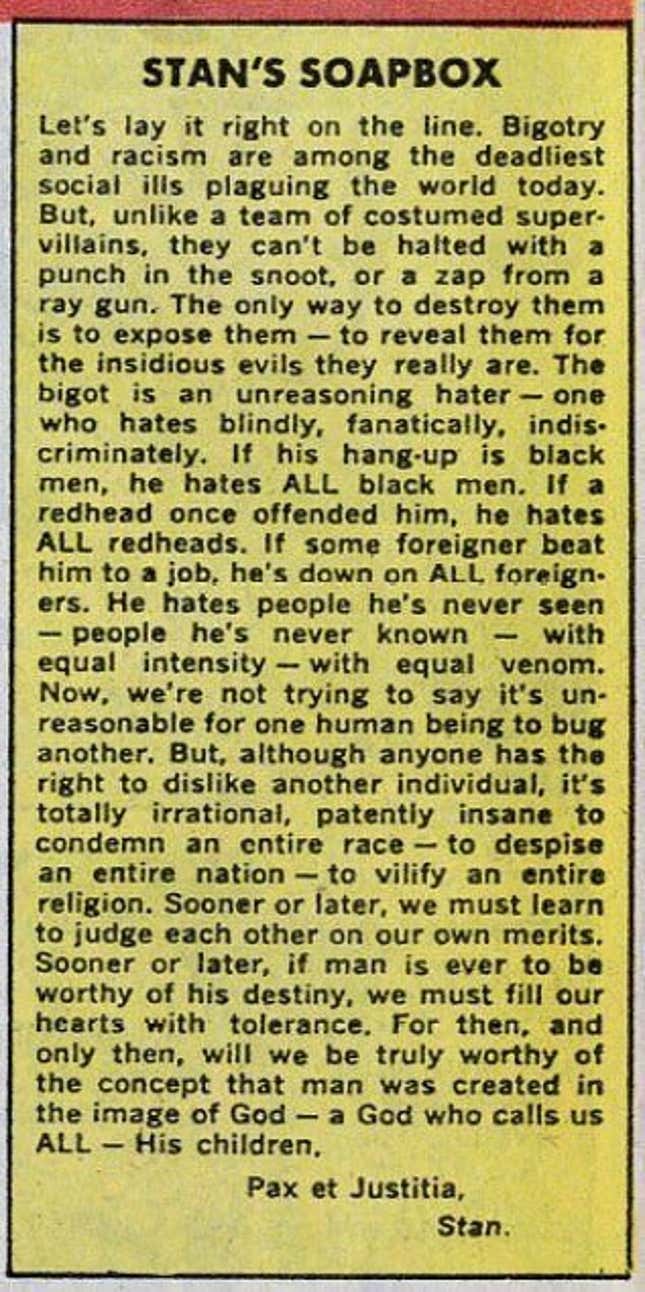

It wasn’t until later in life, when I started studying and teaching about comics instead of just reading them, that I learned that none of this was a fluke. Stan Lee was an activist artist, a Jewish guy born to Romanian immigrant parents in New York who hated bigotry. He was explicit about it in his Stan’s Soapbox editorials that ran across all Marvel Comics. He called bigots “Low IQ Yo-Yos,” he said that anybody who generalized about blacks, women, Italians or whoever hadn’t truly evolved as a person.

He was doing this in comic pages when mainstream newspaper editorials were still deciding if black folks should be able to live where they wanted. When Marvel Comics were afraid that the Black Panther character would be associated with the Black Panther political movement, Stan Lee pushed for T’Challa to keep his name (at one point they wanted to call him Coal Tiger). All of this at a time when even having a black person in a comic was still considered controversial. Just last October, Lee posted a spontaneous video on the Marvel’s YouTube page stating the foundation of Marvel Comics was to fight for equality and battle against bigotry and injustice.

I don’t know if it was Charlottesville, Va., or Donald Trump that inspired the video but the fact remains that Stan Lee was steadfast in his belief that super-heroes should look and sound like the world around us; that they needed to reflect the best in people while tackling the worst of human instincts.

I’m not a kid anymore, I’m not waking up to hear Stan Lee’s voice narrate Spider-Man and his Amazing Friends on Saturday mornings. I can drive myself to the movies where I see Stan Lee cameos in Marvel and D.C. films. I don’t look up at the ceilings in D.C.’s Union Station and imagine what it would it would be like to climb on the walls like Spider-Man (well, actually I still do but not as often).

Yet, every week I teach a class at Morgan State University about comic book politics and history, I still go to the comic shop every Wednesday, I have interviewed Ta-Nehisi Coates twice about the Black Panther comic book, I wrote about how the Falcon made the Captain America movies the blackest Marvel film ever. I’ve waxed poetic about how the X-Men are the single most progressive pop culture icons in Gen-X culture.

All of this is thanks to Stan Lee, who showed this kid that a love of art and politics didn’t have to exist in separate universes; that blackness was as heroic as anything else; and that when you have power—even just the power to draw a few characters on a page—you have a responsibility to make those characters count for something.

Lee would end most of his personal appearances and cameos with “Excelsior” — the Latin phrase that translates roughly as “higher.”

Thanks for all your help, Stan Lee. I hope you’re out there somewhere exploring the cosmos, swinging from the ceilings, knowing that you made the world a better place.

Excelsior, indeed.