Halloween was one of my favorite annual celebrations as a child—until my reckoning with racism almost claimed that joy.

I was raised in a safe, diverse and bustling town in New Jersey, just about 25 minutes away from the Big Apple, where the treat-filled day was taken very seriously. My school in that small town encouraged us kids to dress up in costumes by hosting a parade where we would march through the streets showing off our ghoulish or superhero-themed looks. I remember mom taking me and my brother to Party City one year and instructing us to stay within her price range.

“Nothing too expensive,” she warned, pointing to the affordable section of children’s costumes plastered onto the store’s walls on display.

I scanned my options: a purple witch costume pictured with a broom and long, black matching wig as accessories; a nurse or doctor; a pumpkin; a fairy; and various cartoon and superhero characters. The photos of the child models wearing the costumes all revealed children with silky straight hair and white skin. None of them looked like me; but I immediately identified with one choice, nonetheless. I wanted to be Superwoman.

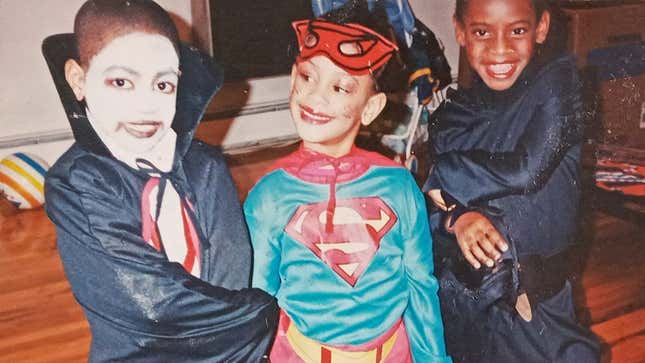

On the day of the parade, I slipped into my costume and mom put glitter, lipstick and red blush on my face. She carefully braided my hair and secured two buns with matching bubble barrettes. I spent that day parading, eating cupcakes topped with candy corn, trick-or-treating in my town and then retreated home to stuff my face with candy, eat popcorn and watch my favorite Halloween movie: Hocus Pocus. I loved the tale of love, magic spells and witches, even if none of the characters in the movie looked the way I did.

In fact, by then, I had grown accustomed to the fact that it was rare for anything having to do with the spooky day to have faces that were brown, like mine. The world of magic, ghosts, witches and goblins was a white one. As a little Black girl, I was just happy to be able to be a part of it. But as I grew older, participation in the festivities became more troubling.

“It’s just a costume,” I heard a white man say in between hysterical laughs when I was in my 20s and at a bar in New York City.

He had his face painted brown and was wearing a long, dreadlocked wig. I cringed and told my girlfriend I was ready to leave. But I still couldn’t escape the onslaught of racist costumes, headlines about celebrities who wore blackface in any given year (as photos revealed Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau did) and the way the entire celebration felt so whitewashed. By then, I was very sensitive to racism and just beginning to truly accept the way it permeated almost everything in my American life. I was exhausted— gutted from finally reckoning with the reality of being raised in a world of white supremacy.

I wanted to write off participating in the celebration all together. Heck, I wanted to write off American racism all together. After I graduated college, I moved back to the land of my birth, the islands of Trinidad and Tobago, and breathed a deep sigh of relief. In a country full of brown and Black faces, I no longer had to worry about being a minority—so I tried to embrace a new definition of being a modern Black woman. I listened to parang and sipped sorrel instead of indulging in songs about white Christmases while drinking eggnog. I participated in Carnival and “wine down d place,” casting aside the cloak of westernized respectability.

But Halloween was something I just wasn’t ready to entirely let go of. Years after my initial move, I had my own kids, and I still wanted them to experience the joy I had of dressing up, telling scary stories and chomping down treats.

“Can I be a vampire?” My daughter asked a few weeks ago, when she heard the annual celebration was nearing.

I felt cornered. For so long, I had been thinking about what I didn’t want my Black daughter to experience—the sting of minority status or having to participate in traditions that didn’t have anything to do with her own heritage— that I hadn’t really stopped to think of what I did want for her. The truth is that I wanted her to have Halloween, but a version of it that centered her Blackness.

“Have you ever heard of a soucouyant?” I retorted after a long pause.

She shook her head “no” as a look of intrigue spread across her face. I quickly devised the scariest version of a story about the witch woman who tears her skin off at night and terrorizes people and animals by sucking their blood. My daughter listened, wide-eyed.

“Have you ever seen one?” she asked in a whisper when I finished divulging the tale.

I nodded my head yes and she gasped, then scurried off into another room. She returned a few minutes later with my son and my nephew, insisting I share the scary story with them, too. After that evening, they were hooked—and I was too. I ordered a book of Trinidad and Tobago folklore to reacquaint myself with the cultural stories that had taken a backseat to the more Americanized ones for far too long in my life. We flipped through page after page filled with brown and Black faces about shape-shifting Lagahoos, the devilish La Diablesse and other jumbies and ghoulish creatures that haunt the Caribbean.

“If you ever hear children laughing, go get an adult to check it out because they can be Douens (dead, unbaptized babies who now are trapped and roam the Earth believed to lure children away from their families),” I warned with a sly grin.

I replaced stories about leprechauns with our own version, Bucks—supernatural, furry, troll-like tricksters said to bestow wealth and success on anyone that captures one, but usually at an unknown cost.

“Bon jour, vieux Papa,” the kids rehearsed their polite greeting, the only known way to survive an encounter with the legendary Papa Bois, the cloven-hoofed little old man with superhuman strength who wanders the woods.

With every new folk character, we felt more connected to the tapestry of colorful stories woven by our ancestors and passed down through generations.

I learned about old, scary sites and the urban legends that claimed they were haunted by enslaved Africans who were murdered by nuns. I bought materials so we could fashion our own scary masks and costumes from the new stories we learned. And as we sat outside under a full moon cutting materials and whispering more scary tales amongst ourselves and making plans to bake a treat-filled graveyard-themed cake, I felt whole. My reckoning with racism wasn’t just a matter of rejecting the things that made me feel marginalized as a Black woman in America. I finally understood, it was about reclaiming what slavery and colonialism has stolen: our stories, our voices and our identities.