The great journalist and civil rights activist, Ida B. Wells once said, “The way to right wrongs is to turn the light of truth upon them.” This Women’s History Month, I want to turn the light of truth on three women whose lives intersected to right the wrong of segregated public transportation. These women deserve recognition for their contributions, but their places in history and the public consciousness is best described by someone with whom I have little in common, but whose construct in this instance I agree with wholeheartedly.

Former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld once said, “there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say, we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don’t know that we don’t know.” Let’s apply this construct to three women whose courage and commitment resulted in a very historic result, the desegregation of public transportation. When this topic comes up, everyone’s mind immediately goes to the “known known,” Rosa Parks.

We all have heard the story of Parks’ refusal to give up her seat on a Montgomery, Ala., bus to a white passenger. Her action led to a lawsuit that went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, and the court’s ruling in her favor is credited with desegregating our country’s public transportation system. Parks’ story is well known, and her legacy is cemented in our history books. But there is a “known unknown” in the development of the life and legacy of Rosa Parks. She is Septima Poinsette Clark.

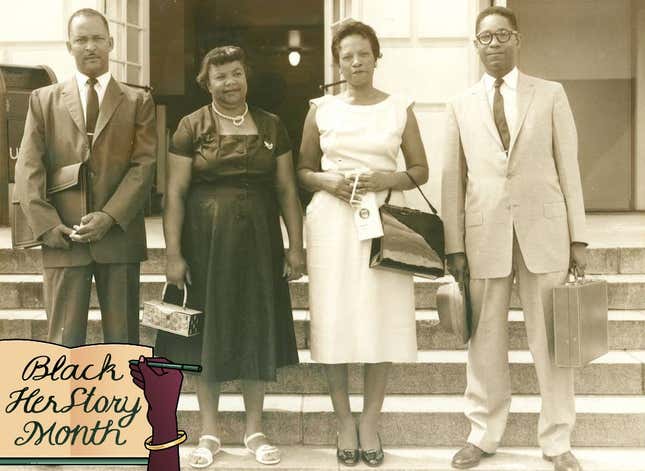

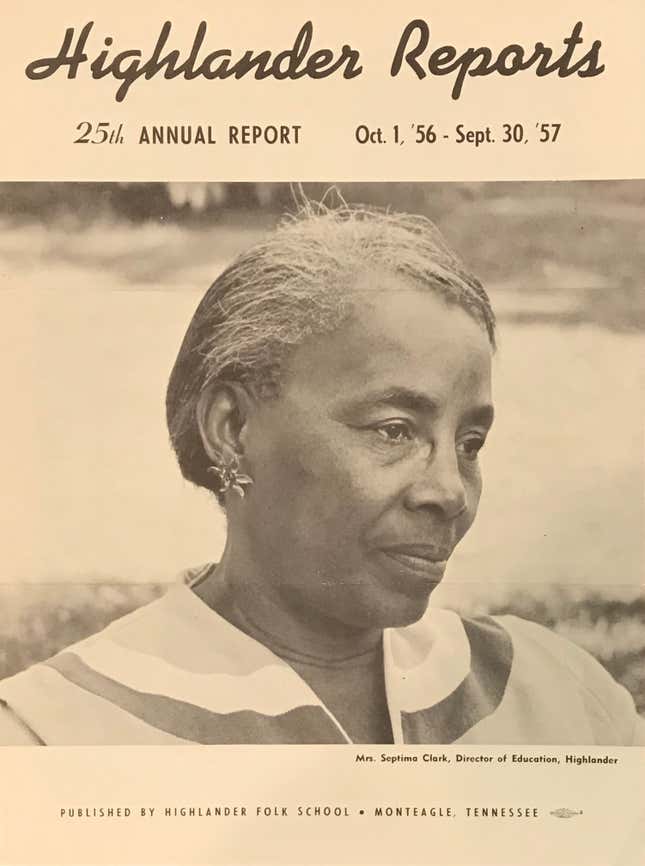

Clark was a public school teacher in South Carolina who was fired in the early 1950s when she refused to renounce her membership in the NAACP. Because of her steely will, incredible teaching skills and intergenerational acumen, she was subsequently recruited to teach non-violence and civil disobedience at the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee. Rosa Parks was one of those she taught and her skills and demeanor earned her the moniker, “Mother of the Movement” by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

I got to know and work with Septima when she returned to Charleston in the 1960s. Although she was 42 years my senior, her uniqueness was of such that I was comfortable referring to her by her first name. King always visited Septima whenever he was in Charleston. In fact, I shared lunch with them in her home during his last visit to Charleston on July 30, 1967.

Additionally, there is an “unknown unknown” in the quest to integrate public transportation.

Sarah Mae Flemming was also a South Carolinian. Her story has been lost to history, and it is time to revive it. Seventeen months before Rosa Parks’ refusal to give up her seat on the Montgomery bus, Flemming defied a Columbia, S.C., bus driver’s demand to move to the back of the bus after a hard day’s work as a domestic. She received a punch in the gut and expulsion from the bus for her defiance.

In November 1956, Flemming’s case against South Carolina Electric & Gas, who owned Columbia’s transit buses at the time, was decided in her favor by the U.S. Supreme Court. Her case set the precedent and was cited in Rosa Parks’ subsequent lawsuit.

Sarah Mae Flemming wasn’t trained in civil disobedience. Her action was not part of a well-orchestrated plan to challenge unjust laws. Her refusal to give up her seat was sparked by her belief that no white person was more entitled to a seat on the bus than she. Her action was a true profile in courage, yet she remains an unsung hero despite her significant contributions to history.

This Women’s History Month, is a good time to highlight those “unknown unknowns” in our midst. I encourage us to elevate those women in our lives who have not sought the limelight or received recognition but who have lifted so many others on their shoulders. Let us turn the light of truth on their extraordinary actions that help to repair our faults and move us closer to making America’s greatness accessible and affordable for all.

U.S. Rep. James E. Clyburn represents South Carolina’s 6th District and is House Majority Whip.