Updated as of 11/19/2022 at 11:00 a.m. ET

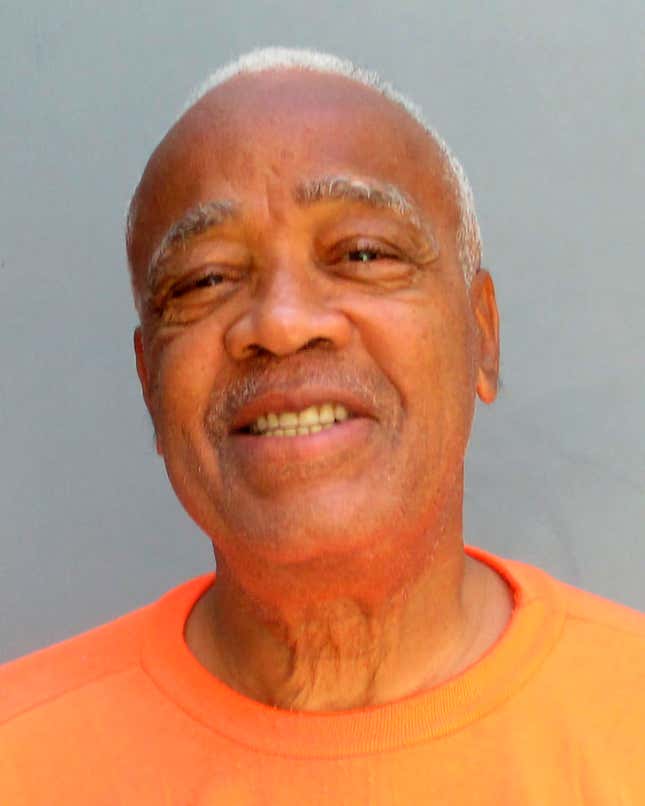

On Wednesday at 10:34 am, 76-year-old Murray Hooper was executed by the state of Arizona by lethal injection.

In his final moments, rather than plead his innocence as he had for the last forty years, Hooper took to comforting those closest to him.

“It’s all been said. Let it be done,” Hooper said, according to the Associated Press. “Don’t cry for me – don’t be sad.”

It took roughly fifteen minutes for the drugs to kill Hooper, according to the Associated Press reporters, who gathered along with dozens of other witnesses, including Hooper’s friends, attorneys, and family members, to watch the execution.

Hooper was the third person executed by the state of Arizona since May of this year.

In 1980, Hooper, who was Black, was among three men convicted of carrying out a contract killing in Phoenix, Arizona, allegedly on the orders of a Chicago crime syndicate. The other two men have since passed away while in prison.

For the last forty years, Hooper has maintained his innocence, claiming he was framed for the horrific crime which took the lives of Helen Phelps and Pat Redmond.

The case against him and his three defendants relied entirely on eye-witness testimony from one of the sole survivors, Marilyn Redmond, who was white. According to the Intercept, Redmond had originally told police that she was unable to identify the perpetrators because she was “afraid to look at them.”

However, Hooper was ultimately convicted in both Illinois and Arizona by an all-white jury. Although his conviction in Illinois was later overturned.

There was never any physical evidence connecting Hooper to the crime. But on Monday, the state denied his attorney’s request to test for DNA and fingerprint evidence that could exonerate him.

“No physical evidence links him to the crime and Mr. Hooper’s execution should not be carried out until an analysis of key fingerprint and DNA evidence,” Kelly Culshaw, an assistant federal public defender who represented Hooper, wrote to CBS News in a statement days before his death.

In a hail mary attempt, Hooper’s lawyers had asked the Supreme Court for an appeal of his case on the grounds of claims that Redmond had failed to identify him in a photo lineup. That appeal was ultimately rejected and Hooper was killed just hours later.

Race has undoubtedly played a large role in this case and the subsequent media attention around Hooper’s execution, especially because the person who identified Redmond in the lineup is white.

Cross-racial identification can often be unreliable. In roughly 66 of 216 wrongful convictions overturned using DNA testing by the Innocence Project, cross-racial eyewitness identification was used as evidence to convict an innocent defendant.

The race of the defendant and of the victim also plays heavily into who receives the death penalty in the United States.

Despite making up roughly 13 percent of the US population, Black Americans represent roughly 34 percent of all executions since 1976, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. The larger bias persists in the race of the victim. In approximately 75 percent of all death penalty executions since 1976, the victim was white, far outstripping the percentage of murder victims who identified as white.

In his final days, Hooper spoke to reporters about his case, stating that if his life couldn’t be spared, at least he could get his truth to the public.

“It took 32 years” for the truth to come out in Illinois, Hooper told the Intercept days before his death. “Even if they got me, at least it’s out there.”