On a brisk day in Montreal, Quebec in November 2019, I entered the sound stage for the production of The United States vs. Billie Holiday. In turn, I also entered the eccentric world of director Lee Daniels, who noted that he chose Montreal because it was the closest resemblance to a past Harlem that doesn’t even exist in the actual Harlem anymore. The Root was not only the first outlet to visit the set of The United States vs. Billie Holiday in its final two weeks of production, but we later learned we were the only outlet to obtain on-set coverage.

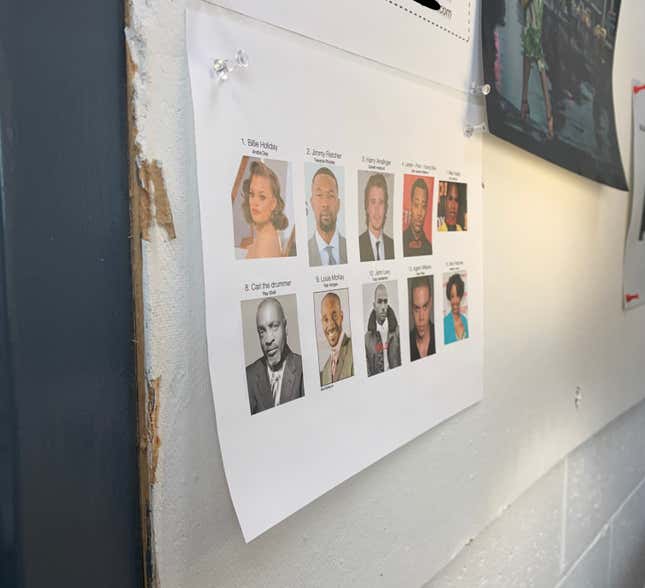

The United States vs. Billie Holiday is penned by Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Suzan-Lori Parks, based on the chapter “The Black Hand” on Holiday in Johann Mari’s 2015 bestselling book, Chasing The Scream: The First and Last Days of the War on Drugs. The film follows Holiday (Andra Day), who is targeted by the then Harry J. Anslinger-led Federal Department of Narcotics after her iconic live performance of “Strange Fruit.” She subsequently engages in a tumultuous affair with federal agent Jimmy Fletcher (Trevante Rhodes), who takes the lead on-the-ground role in the undercover sting operation against her. The film also stars Da’Vine Joy Randolph, Natasha Lyonne, Garrett Hedlund, Rob Morgan, Miss Lawrence, Tyler James Williams, Evan Ross and Tone Bell.

I was transported to a time long before our own as I heard Day’s raspy “Billie” voice repeat the line “I’ve been tinkering with a new tune” during multiple takes as a teaser to her live performance of “Lady Sings the Blues,” set in a recreation of the once-famed Café Society. I sat staring at the video village monitors alongside Jazz Foundation of America Executive Director Joseph Petrucelli as Wray Downes, a pianist who actually had the privilege of playing for Billie and consulted on the film (and who I was recently notified has since died in March 2020), told us riveting anecdotes about the real woman known as “Lady Day,” giving deeper context to the way Day was portraying her.

Almost 50 years after the debut of Lady Sings the Blues starring Diana Ross—a “Black elegance” film which Daniels says inspired his own filmmaking career—the Academy Award-nominated director is now once again dipping his toes into the deep well of Black history.

“I was nervous because I hadn’t done anything [in film] since The Butler, and [with Billie Holiday], I found something that really spoke to the core of who it is that I am,” Daniels told me of his “espionage love story.” On set that day, I was able to escape the video village for a bit to shadow the director and witness him in his helming element. Whether screaming “yaaaaassss!” to one of the background actors making a choice he loved or completely engrossed in the playback of the dailies (he was particularly eager about showing me a pivotal filmed sequence involving a lynching), I had the privilege of better understanding how Daniels’ creative quirks translate to the big screen.

As if a jazz musician himself, Daniels is improvisational and spontaneous while simultaneously very introspective—you can ask him a question and he’ll answer it, then immerse himself deep in thought and abruptly add to the answer right as you’re moving on to the next. Simply put, I got to know a bit more about Daniels that day.

I also sat down with the producer-director last summer for the first edition of The Root Institute series, which was a reunion of sorts, after my set visit. There, he reiterated what he had told me many months prior—that Holiday was an activist and a civil rights leader. Having grown up with Ross’ portrayal of the jazz singer, Daniels wanted to touch upon another part of Holiday’s life in his film; this wasn’t going to be a remake of his beloved Lady Sings the Blues, he told me, but an aspect he believed deserved extra exploration after learning about it.

In her first major film role, The Grammy-nominated Day has taken on the gravity of portraying Holiday at a particularly vulnerable point in her life, and clearly took the responsibility very seriously, even going slightly “method” for the role. When I arrived on set, I was told I may get some time with the actors depending on their schedules, but Day’s availability was off-limits from the start; I barely laid eyes on her beyond the monitors (and one quick glimpse at her undergoing “last looks” in makeup). In fact, she reportedly never turned “off” her Billie; word on the set was that Day traipsed the cobbled streets of Montreal completely in character as the late chanteuse, only getting two hours of sleep every night.

“I didn’t want [Day] at first, I wasn’t sure who I wanted,” Daniels revealed. “She came in and she auditioned and she was the best auditioner. I wasn’t really familiar with her work [prior]. Her theme song—(he starts singing the hook to “Rise Up”)—that was on Star. They sang that song. But, I don’t know, it was something about [her]...I just was not feeling her. So many people told me that I had to read her. [I figured], it didn’t hurt to read her. Then I met her, read her and she just blew me away. There were many big-name women that I sat down [with], but this...it felt like [Andra] wasn’t even acting.”

That approach to acting is Daniels’ favorite, as he isn’t a fan of overacting—instead, he prefers actors to be. As for Rhodes, it was the young actor’s mysteriousness that attracted Daniels—something I also briefly experienced when we were introduced and he gave me a quiet gesture of gratitude and welcome.

Daniels had his perfect stars, but what about making sure the thing gets made? Enter Jordan Fudge, the co-founder of New Slate Ventures, a $100 million TV and film fund that has already seen success with Radha Blank’s The Forty-Year-Old-Version (acquired by Netflix) and hopes to see the same with Billie Holiday. Before I shook Fudge’s hand, his intro via the unit publicist opened with, “this project wouldn’t have happened if it wasn’t for Jordan.”

“I am in the position where I can just give him the resources that he needs to do without interference—without me poking and prodding at his process,” the financier says of his collaboration with Daniels. “I think that that’s been what has made our working relationship great is that I trust the people that I work with and invested in, so to speak. I give them the autonomy to bring us the stories that they think the screen needs.”

“I could’ve done this movie at many different studios for a budget [where they’d be like] ‘Here is a couple of dollars, go do a movie.’ That’s what they expect from us. No, we’re going to have Prada doing the clothes,” Daniels said firmly.

When I talked to Fudge about Billie Holiday’s distribution fate, he wasn’t so much focused on technicalities such as the release schedule as he was on making “the best film possible.” However, he did note at the time that he had his eyes on the festival circuit.

“I’m really excited about this new streaming environment that we’re in,” Fudge added. “I think that there’s been a lot of controversy around it, but I genuinely see it as something that’s good. I love the idea of a theatrical exhibition, but I do believe—specifically for groups that are niche or minorities or are in some ways marginalized or disenfranchised—that streaming has the ability to democratize the type of content that gets created.”

Little did we know just how much weight that statement would carry. When I visited the set in 2019, a major studio had yet to acquire the film. Film production can be an unpredictable beast on its own, but the global pandemic completely shattered any hopes of a standard theatrical distribution. Paramount would scoop Billie Holiday up in July of 2020; it wasn’t until December that Hulu would acquire the domestic distribution rights.

In spite of the racial reckoning of 2020, the obstacles many Black filmmakers and producers face today are still tantamount to racial silencing—a tale as old as time, not only in the Hollywood industry, but in America, period.

“I think what I’m most excited about the audience taking away from this film is realizing the source of a lot of what has emerged as this country’s playbook with respect to race,” Fudge said. “They’ll demonize a part of our population, usually a music-making or art-creating part of our population, take that and create a narrative that makes us seem ‘less than’ or ‘other.’ Anslinger, as we know, started the war on drugs and used what was a very innocuous group of people that were making music in Harlem on their own—really creating some of the best art that the period had to offer—and turned it into something monstrous, vilified and something that Congress even had gotten involved with—when at the same time, white artists were doing the same thing and they were allowed to go.”

Billie’s “Strange Fruit” served as a mirror to a racist America—and, as Fudge noted, was a very early form of protest art that remains relevant to this day. “[Billie] expressed it through her art. That’s what I do; I express my shit through my art,” Daniels noted.

The nervousness Daniels alluded to earlier in the day was completely apparent in his restless demeanor, save one moment where he pointedly leaned in and looked me right in the eye as we chatted at the end of the day in his trailer.

“I’m walking on eggshells making sure that everything I say is accurate—everything she says, [I’ve gotten from] a zillion books, documentaries, interviews with people that played with her...to make sure I do right by her legacy,” Daniels said. “I have to do right by her. It’s as if she’s talking to me like, ‘You got to do right by me.’ And I did that because we both have experienced addictions. I understand her in a way and appreciate it in a way that other filmmakers won’t.”

“There are no stunts here; this is the Black truth,” Daniels concluded.

The United States vs. Billie Holiday debuts on Hulu on Feb. 26.