Writer George M. Johnson has yet to see themself represented accurately in media. Growing up black and questioning in Plainfield, N.J., they were simply aware that they were “different.” Feeling neither entirely boy nor girl and devoid of the language to express their evolving identity, the only thing they knew for sure at a very early age was that “safety trumped satisfaction.”

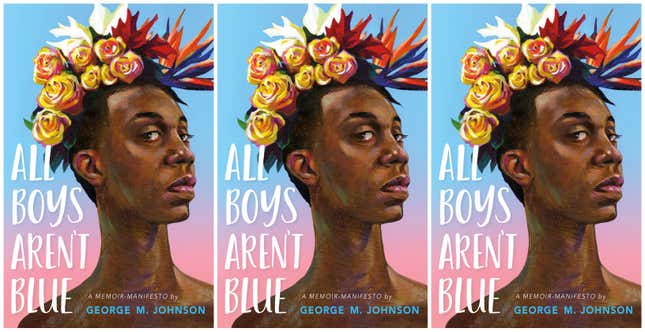

Now in their 30s, Johnson is revisiting their journey into adulthood and queerness in All Boys Aren’t Blue, a “memoir-manifesto” published by Farrar Straus Giroux debuting on Tuesday, April 28, that was written in hopes of making the journey easier—and hopefully, safer—for a new generation. While perhaps not the expected fare of the young adult category, Johnson tells The Root that the genre provided an unexpected opportunity.

“Nothing like this existed for young adults, and at first I was hesitant because I wasn’t sure I would be able to tell the total truth and I knew there were some stories that were going to go there,” they explained. “So for me, it then became about what my whole activism is set up around, which is really helping and changing the narrative of black children, specifically black queer children. I knew I wanted to create something that would stand the test of time and be here as a guide for so many who have come and who have gone whose stories have just never been seen in the world.”

But there’s plenty for fully-grown adults to glean from Johnson’s story, as well; especially for those seeking to create a safe and open environment for the children in their care. While All Boys Aren’t Blue covers topics like gender identity, sexual awakening and sexual abuse, they are seamlessly interwoven with discussions of family, unconditional love, how black history is taught in schools, and the unexpected acceptance Johnson ultimately found within a black fraternity.

“My blackness is everything because I believe that blackness is inherently queer,” they say. “For me, I knew I had a duty: if I’m going to talk about this, I want to talk about the whole picture of how I got here.”

“The whole reasoning of the book was to allow parents to understand your child has a whole world going on outside of you, and it will behoove you to invest in that world with your child,” Johnson later adds. “You can’t see the thoughts that your child is processing, and I wanted parents, and guardians, and teachers, and whoever read this book to understand this is just not about some salacious tale about my first time having sex, and molestation and sexual assault; these are real-life things that are going to happen to our children because they are happening every day to our children. To deny them the opportunity to read about it is just a disservice to them because then they don’t know how to navigate it when it occurs to them.”

Most of all, Johnson wants black children like the one they once were to have space to safely be “black, queer, and here,” as they titled the introduction to All Boys Aren’t Blue.

“The first thing I want them to know is other people like them exist. A lot of times, it’s hard to even know how many of you are out there. I struggled with that growing up, not seeing myself—I still struggle with it now,” they admit. “The second thing would be to understand why I wrote the book with so much empathy for others—even in their wronging of me—because we have to look at our parents, our guardians, our friends as total people who make mistakes, who have faults, too…I hope another thing is that they realize you can create family outside your family as I did…We exist in all spaces; we’re here, we exist and we have community in a lot of places.”

The following is an excerpt from All Boys Aren’t Blue: A Memoir Manifesto, published by Farrar Straus Giroux and condensed for length.

I was five years old when my teeth got kicked out. It was my first trauma.

By that age, I already knew I was different, even though I didn’t have the language to explain it or maturity to understand fully what “different” meant. I wasn’t gravitating toward typical boy things, like sports, trucks, and so on. I liked baby dolls and doing hair. I could sense that the feelings I had inside of me weren’t “right” by society’s standards either. I remember that on Valentine’s Day, the boys were supposed to give their “crush” a card. Not wanting to give mine to a boy, I gave it to a girl who was clearly a tomboy even at that age. I was always attracted to the company of boys.

I used to daydream a lot as a little boy. But in my daydreams, I was always a girl. I would daydream about having long hair and wearing dresses. And looking back, it wasn’t because I thought I was in the wrong body, but because of how I acted more girly. I thought a girl was the only thing I could be.

I struggled with being unable to express myself in my fullest identity. One that would encompass all the things that I liked while still existing in the body of a boy. However, I was old enough to know that I would find safety only in the arms of suppression—hiding my true self—because let’s face it, kids can be cruel. I integrated well, though, or so I believed at the time. I became a world-class actor by the age of five, able to blend in with the boys and girls without a person ever questioning my effeminate nature. Then again, we were so little—maybe all the children were just as naïve as I was about the kids who surrounded them.

I was five years old when my teeth were kicked out. It was my introduction to trauma, and now, I’m ready to start there.

At that age, I wasn’t allowed to walk home from school by myself. So, I walked home with my older cousins, Little Rall and Rasul. During that time, my cousins lived with our grandmother, who also happened to be our primary caregiver—since our parents worked long hours. Walking to Nanny’s house after school was our routine. I usually walked holding hands with Little Rall while Rasul went ahead. We would take the back way every day, which meant walking behind the school, through the football and baseball fields, to the street one block over from Nanny’s house. On a normal day, that walk took less than ten minutes. Living so close to the school, I’m sure Nanny never imagined that within those ten minutes, her grandchild’s life would be forever scarred.

The memory is vivid. I can still smell the air from that day, sunny and mild springlike weather. That walk to my grandmother’s started just like any other, with me holding hands with Rall, while Rasul sped ahead of us. We were at the corner of Lansdowne and Marshall on the lawn of the corner house when we ran into a group of kids from the neighborhood that I didn’t recognize.

They had to be about my cousins’ ages—around nine or ten years old. The main kid was white. To this day when we talk about it, we use his full name, but I won’t say it here. The other kids were Black and white if memory serves me correctly. My cousins knew who they were, I guessed, because they immediately began arguing. When I sit with this memory, there is no sound in the moment. I can see it. When I write about it now, my body can feel it. But as I close my eyes to think about it, the situation was instant chaos. I got extremely nervous. I just held on to Rall’s hand even tighter.

There were three of us and six of them, which was really two on six because what did a five-year-old know about fighting? The arguing kept getting more intense with my fear growing as the boys got closer, in each other’s faces. It’s strange how near to home and safety one can be when some of the most traumatic things in life occur. I used to wonder what would’ve happened if we had walked a different route that day, or left the school five minutes earlier? Would my life have turned out any different?

Before I knew it, the argument broke into a fight, and I, the invisible boy, somehow became the biggest target. As my cousins squared up with three of the boys, two others grabbed me by my arms and held me on the ground. I screamed for help, as it was all I could do. The third kid swung his leg and kicked me in the face. Then he pulled his leg back again and kicked even harder.

My teeth shattered like glass hitting the concrete. In that moment, I felt nothing. It was as if it were all a dream. Then I felt the pain. I also felt an emotion I had never experienced before: rage. I didn’t fully understand the feeling at the time—had not yet had the pleasure of introducing myself to it. The tears that streamed down my face were no longer about pain. I was now crying tears of anger. Tears of rage.

That rage was enough to stop the boy from ever bringing a third kick to my mouth. I somehow broke free, lunged forward, and bit his leg with the teeth I had remaining. He screamed so loud as I bit through his jeans. By this time, my cousins had handled the other three boys and saw what had happened to me. They ran toward us together, which made all my assaulters retreat. They grabbed my book bag, and said, “Run to the house, Matt.”

So, I did. Ironically, this moment marked the beginning of my track career, which I would pursue from elementary to high school. Sound is now back on in the memory at this point. I can hear my crying as I ran home. I got to my grandmother’s house, and I continued to cry—bloody mouth, busted lip, and baby teeth knocked out.

“What happened?” yelled Nanny.

“We got jumped,” my cousins explained. Nanny went and got ice and wrapped it in a paper towel, and she told me to hold it to my face.

It all gets a little hazy after that, as I remember bits and pieces of what occurred. My mother left work immediately to get to Nanny’s. She sent an officer ahead to meet us at the house to take down the report. When my mother got there, she came and checked on me immediately. She sat in one of the dining room chairs and had me sit in her lap with her arms around me.

I finally calmed down once my mother held me. At some point, my uncles showed up and were sitting with us all. My cousins were still visibly upset. I sat there in silence, feeling the rise and fall of my mother’s chest with each breath she took. The officer began asking my cousins what happened, and they told their story. The officer asked me to open my mouth so he could note the damage in his report. I recall not speaking for hours after this happened.

When I close my eyes now, I see it all happening as if it were some out-of-body experience. I think back on that day a lot. I wish I knew what motivated the attack. Could it have been because I was effeminate? Could it have been a race thing, since the main assaulter was a white boy from a different part of the neighborhood? Could it have simply been the toxic behaviors we teach boys about fighting and earning manhood? I know that impact and intent always play a role, so even if their intent wasn’t those things, the impact would forever change me anyway.

There were no counselors or therapy sessions to help me work through what had happened. Therapy is still very much a taboo subject in the Black community. Those who are seen as having issues with their mental health face a lot of stigma and discrimination because mental health is often conflated with mental illness. So rather than having their child labeled as something hurtful, my parents did the best they could with what they knew.

We did what we always did as a family—we loved on each other even harder. In that moment, my mother just held me, and we sat there together for a long while. Eventually, she took me home. But the next day became just that. The next day. What happened the day before was to be forgotten, or better yet, buried.

Unfortunately, part of what I forgot was how to smile. I immediately became self-conscious about smiling. It’s something I’ve struggled to remedy even as an adult. Because my baby teeth had been kicked out, my adult teeth—almost “buck teeth”—grew in extremely early. Adult-size teeth on a seven-year-old are very odd- looking, and it brought me a whole new type of attention I wasn’t looking for. My lips became protection for the smile that was stolen. Picture after picture after picture, I refused to smile. There are photos of me at seven, nine, thirteen, twenty-two, and twenty-nine years old where I refuse to smile.

Every now and again, my mom will find a picture of me with my teeth showing. There aren’t many of them, though. And when I look at them, sometimes I cringe. Other times, I’ve actually teared up, wondering if I was truly happy in that picture or if I simply felt the need to smile because someone said, “Smile, Matt” and I obliged. The fact that I don’t feel happy when I look at those images lets me know there wasn’t any happiness when I took them.

What did I look like to others—a child who rarely smiled? Did they ever take it as a sign that I was actually dealing with a trauma I couldn’t get past? Or did they pass it off as a “boys will be boys” thing that I would eventually grow out of? To go years without smiling in pictures, rarely being questioned why, leaves me to wonder how many signs of trauma we miss or ignore in Black children.

I used to think that I had gotten over it if I took a good picture where I was smiling. But it only required one bad smiling pic to remind me of how trauma has a funny way of showing up in our lives during the moments when we least expect it. It can be an action that we write off as something else, when really it is the manifestation of a pain we had refused to deal with. A trauma that no one helped us fully process or that they didn’t have the skills to even know we needed help for. Boys aren’t supposed to cry, so hold that shit in. Sometimes to the grave.

All Boys Aren’t Blue: A Memoir-Manifesto by George M. Johnson will be published on Tuesday, April 28 and is available for pre-order now.

Updated: Thursday, 7/30/20 at 9:05 p.m., ET: An earlier version of this article incorrectly used “he/him” pronouns; Johnson has since clarified that “they/them” is their preference. The post has been updated to reflect this.

(Updated 3/3/22 with new details)