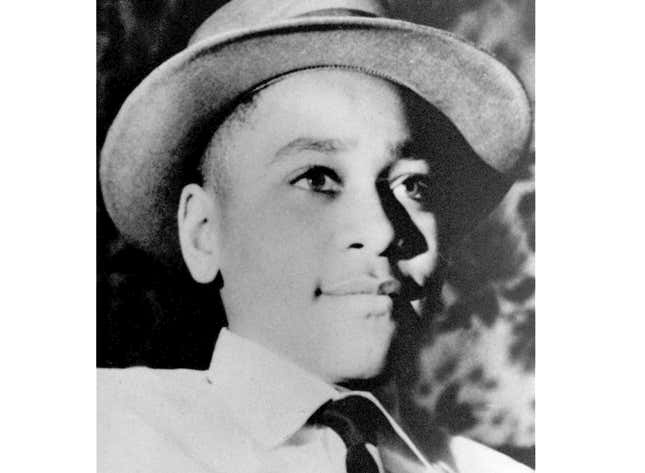

For more than 50 years, there was no marker at all to commemorate the lynching of Emmett Till, the 14-year-old Chicago boy brutally murdered by two white men while visiting his family in Mississippi. That changed in 2008 when the first memorial was erected on the banks of the Tallahatchie River, where local authorities first pulled Till’s body from the water—but that, of course, is not where the story ends. Not in Mississippi, and not in America.

The sign has been replaced three times in 11 years: it’s been stolen and riddled with bullet holes as a result of repeated, deliberate acts of vandalism (the sign, sitting at a remote spot on the Tallahatchie, is not easily accessible to mere passersby). On Saturday, a fourth iteration of the memorial plaque went up; in an effort to dissuade future vandals, the Washington Post reports, the sign weighs 500 lbs. It’s also bulletproof.

Till’s family was on site for the dedication of the new memorial; one of his cousins, Airickca Gordon-Taylor, spoke to the New York Times about the signs’ traumatic legacy.

“Vandalism is a hate crime,” Gordon-Taylor, who runs the Mamie Till Mobley Memorial Foundation, said. “Basically my family is still being confronted with a hate crime against Emmett Till and it’s almost 65 years later.”

The new sign—glossy, black, and fashioned out of steel and acrylic by Lite Brite Neon Studio in Brooklyn, N.Y.—is specifically designed to withstand rifle rounds, the Emmett Till Memorial Project says on its site. Inscribed on the plaque is a history of the site—a former steamboat landing. The area was first cleared by enslaved people in 1840 and is believed to be where Till’s body was recovered from the river. But the sign also mentions the history of violence and vandalism that has characterized the mere acknowledgment of Till’s death—and the racial violence that preceded it.

Historian Dave Tell, who wrote the inscription on the sign, told the Post, ‘The vandalism and the bullet holes are part of Till’s story, too.”

From the Post:

“Signs erected here have been stolen, thrown in the river, shot, removed, replaced, and shot again,” the monument reads. “The history of vandalism and activism centered on this site led Emmett Till Memorial Center founder Jerome Little to observe that Graball Landing was both a beacon of racial progress and a trenchant reminder of the progress yet to be made.”

Two white men, Roy Bryant and John William Milam, kidnapped Till from a relative’s home after he was accused of flirting with a white woman at a grocery store in August 1955. The woman, Bryant’s wife Carolyn Bryant Donham, said Till grabbed and wolf-whistled at her; in 2017, she admitted to a historian that none of that had actually happened.

Bryant and Milam were acquitted by an all-white jury. And despite confessing to killing Till in a 1956 interview with Look magazine, they never had to answer for their crimes.

For the Till family, the sturdy new memorial ensures his legacy will outlive the continued assault on his life.

“You’re never going to forget about Emmett Till and that he was here,” Gordon-Taylor told the Times. “Our family has never received judicial justice from the state of Mississippi for Emmett’s murder, so, in some form, this is us saying, ‘Until you do right by us, basically, you’re never going to forget.’”