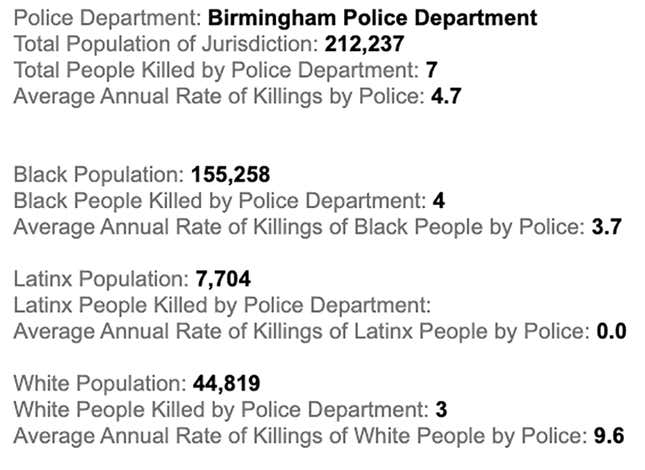

Compared to most cities its size, Birmingham, Ala., didn’t really have a police brutality problem. While extrajudicial killings are always a problem, Birmingham sat near the bottom of the spectrum for American cities with 4.7 police killings per 100,000 citizens, according to Mapping Police Violence. And curiously, as the fourth-blackest city in the nation, Birmingham is one of the few places that actually kills more white people per capita than black. Between 2013 and 2019, law enforcement officers in the city killed four black people and three whites, meaning the city’s white citizens are two-and-a-half times more likely to be killed by a cop.

The city also has a long history of activism. Protests are commonplace in Birmingham. So, when uprisings broke out across the country over the death of George Floyd, Birmingham’s activists began to organize. But with the city’s long legacy in the civil rights movement, what could local activists complain about?

Well, Birmingham still has racism.

First of all, it’s in Alabama. Secondly, the city also has six of the country’s top 50 most unequal school systems, according to Edbuild. It ranks second in the nation for violent crime and has the 34th-most contaminated drinking water. And did I mention it’s in Alabama?

And then there are the Confederate statues.

Even though the city of Birmingham didn’t even exist during the Civil War, the city has three monuments to slave owners, including two Confederate statues in Linn Park, where people gathered to protest police brutality on Sunday. Some people in the crowd were actually free to protest because Alabama is one of the few places in America that closes state offices on June 1 to honor Confederate leader Jefferson Davis (Did I mention the part about Alabama?).

Birmingham had two Confederate statues.

On Sunday, during the rally at Linn Park, the crowd grew violent until the protesters remembered where they were. They began focusing their attention on the statue to the park’s namesake, Charles Linn, a Confederate sailor and industrialist who founded one of Alabama’s largest banks, AmSouth.

They tore that shit down

The crowd also damaged a statue of Thomas Jefferson, in front of the Jefferson County courthouse. But when the crowd turned its ire on the most-hated Confederate statue in the city, the 52-foot obelisk dedicated to traitorous Civil War soldiers and sailors would not come down. They kept trying. The police closed in on the protesters. They would not stop. The statue would not come down.

Then, one of the protesters stepped in to offer some help.

“I actually physically walked into a sea of protestors who were banging and attempting to knock it down,” the protestor told The Root. “They actually tied a rope around the statue and attached it to a [Dodge] 1500 truck. I told them, ‘Please stand down.’ And then I asked them, ‘if you give me a window, I’ll take it down.’

He promised the crowd that if they gave him until noon Tuesday, he would take that shit down forever. And, if the statue didn’t come down by the deadline, people across the city worried that subsequent protests would be uglier and more violent than Sunday’s. The promising protester knew he had to do it. And because everyone in the crowd knew this particular protester hated that statue, they stood down for a day.

The protester was Birmingham Mayor Randall Woodfin.

“The reason is simple,” Woodfin explained to The Root. “I’d rather take it down and receive the punishment from the state than have all the civil unrest in the city, the riots or someone getting hurt taking it down.”

Woodfin explained that he had already seen the violence in the city coming from three different groups.

“The protesters are different from the looters and the looters are different from the anarchists, looters and rioters in the city” Woodfin noted. “I do believe anarchists and the looters co-opt and exploit [the protesters] being there. But I’m also honest, which is why I went out there. I went out there to plead with them, to say: ‘Listen, what you’re doing is wrong. What you’re doing is illegal. However, I understand why you’re doing it. So ultimately, if anybody’s going to do something illegal, it probably should be the city of Birmingham because the weight of us taking it down does not put any lives in jeopardy. It does not cause any more civil unrest. It doesn’t get people arrested. Doesn’t put the police in a position to engage in something where there’s all these other soft targets, which include police headquarters and police precincts in our malls and other commercial districts.”

If this seems reasonable, there is one other thing to consider:

Woodfin was essentially promising to break the law.

Three years ago, Alabama’s history-conscious lawmakers passed the Alabama Memorial Preservation Act of 2017, prohibiting the “relocation, removal, alteration, renaming, or other disturbance of any architecturally significant building, memorial building, memorial street, or monument located on public property which has been in place for 40 or more years.” While the legislation made no specific mention of Confederate memorials or white supremacist traitors to their country, it imposed a $25,000 fine for any municipality that violated the law.

In January 2019, a federal judge voided the law when Birmingham city officials decided to remove a Confederate monument that was erected in a downtown park in 1905. After Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall appealed the decision, Birmingham came up with a workaround: They built a wooden box around the memorial to white people getting their asses kicked. But a federal court eventually imposed the fine on the city for just obstructing the monument.

That still wasn’t enough.

In February, Alabama state Sen. Gerald Allen (R-Tuscaloosa) came up with a unique way to celebrate Black History Month. He introduced a bill that increased the fine to $10,000 per day for any city that disrespected the sanctity of the “lost cause” memorials, a bill that black legislators called “nothing but racism.”

“Should the City of Birmingham proceed with the removal of the monument in question, based upon multiple conversations I have had today, city leaders understand I will perform the duties assigned to me by the Act to pursue a new civil complaint against the city,” said Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall, threatening Woodfin in a press conference the next day. “In the aftermath of last night’s violent outbreak, I have offered the City of Birmingham the support and resources of my office to restore peace to the city.”

By “resources,” Marshall presumably meant “cops,” specifically, Alabama State Troopers.

Woodfin wasn’t studying that shit. Birmingham wasn’t studying that shit.

“Well, we already have one fine, by the way, because we lost the court case when we covered the statue with the box,” Woodfin told The Root. “We already owe $25,000 and they should go about collecting it.”

And then there were the death threats. The Root has obtained audio files of phone calls from the city’s 911 emergency system made by mourners to the lost cause of the Confederate States of America’s white supremacist utopia. The calls giving Woodfin a piece of their racist minds include such hits as:

- “If you take down that statue in Linn Park, that Confederate statue, I’m gonna come down there with an AK-47 and start blowing the pigs away. And the protesters. You hear me?”

- “I’m gonna assassinate nigger Randall Woodfield [sic] and kill that dead nigger. You better call that shit off right now.”

- You think I’m playing? It’ll be all over the news, punk ass. I’m coming down there right now (unintelligible) to blow your fucking head off, asshole

- Fuck off asshole. I’ll hang you from a tree, nigger.

Everyone waited.

On Monday, cops lined up, preparing for the ensuing melee. A GoFundMe page created to pay the penalty raised more than enough money to pay the fine. The racists prepared to assassinate “and kill that dead nigger” (After consulting with the country’s top dead nigger assassination experts, The Root still could not figure out how that works) before Woodfin moved the statue. The protesters woke up on Tuesday morning preparing to show the city and the world that they meant business. And when the groups convened at Linn Park to celebrate or protest the statue’s removal, everyone was disappointed.

The statue was gone.

Using an outside contractor, Woodfin had workers disassemble the monument until about 3 a.m. Tuesday morning.

Asked if he thinks taking down the statue alleviated some of the violence and property damage seen in other cities gripped by uprisings, Woodfin answered simply:

“100 percent.”

“I don’t know what the symbol of oppression in other cities in America is,” Woodfin stated. “I do know a lot of cities have, unfortunately, some form of a tangible thing that represents oppression for black people. And when you have such a vivid situation that happened to George Floyd, you got to remember—even if we are outraged every time an unarmed black man is killed by a white officer—none of us in our lifetime have ever seen an officer take his knee, put it on a man’s neck. After the man dies, his knee is still on his neck. And the entire time the look on his face is ‘I don’t give a damn about this person’s life.’ You better believe in these American cities, separate from the anarchists, separate from the looters, the protesters are going to go to the site of anything they deem oppressive and find a way to demand that it not be there because this warranted outrage of not caring for black people has to come out in some way.”

Perhaps the toughest question Woodfin had to answer was not about the statue, but whether his removal of the oppressive symbol means that the violent protests work.

“Yes,” he said without hesitation. “They made this conversation come back to the face and heart of our city and we had a decision to make. Let’s be clear, that statue was coming down.”

Aside from the dead nigger assassin squad, perhaps the person who is upset about this turn of events is the Alabama attorney general.

“He’s already filed the motion with the court today that we’re in violation of the act again,” Woodfin told The Root. So, less than 24 hours of me taking it down, he’s already filed a motion against us.”

But they have the money, so there should be nothing to worry about, right? Even if the residents miss the statue, they could read books, visit a museum or...

“Damn that statue,” Woodfin said before drifting into a short silence.

“But this is Alabama,” he added.

“That’s what you gotta worry about.”