Prologue

Winter always comes.

Everything dies.

Nothing else is certain.

At the fall of every glorious thing that was ever built, among the ashes and rubble, you will find inevitability. It exists in the tales of once-great dynasties and in the poetry of beautiful kingdoms. The gleaming helmets and the polished swords of fearless warriors will eventually rust away. No crown goes forever untarnished. Every castle is made of sand.

The Kush. The Roman. The Greek. The Egyptian. The Mali. They were all great empires. They are all memories.

But a soul—a soul is a diamond. A soul is forever.

“Invest in the human soul,” said Mary McLeod Bethune. “Who knows, it might be a diamond in the rough.”

If black America were to ever claim an empire, it might rest solely on the investment we made in Historically Black Colleges and Universities. The list of notable HBCU alumni includes the first black Supreme Court justice (Thurgood Marshall, Howard University); the only African-American female billionaire (Oprah Winfrey, Tennessee State University); and the woman whose calculations are credited with sending the first American to space (Katherine Johnson, West Virginia College).

While some HBCUs are experiencing a resurgence, others are struggling to survive. The combination of increased competition, financial scandals and a myriad of self-destructive behavior have created a cloud of gathering storms signaling the impending doom of some of the cornerstones of black America’s empire.

In 2002, Morris Brown College, the only HBCU in Atlanta named for an African American, lost its accreditation due to financial aid fraud and filed for bankruptcy in 2012. Earlier this year, Bennett College lost its accreditation because of a lack of financial resources.

Even the success stories are plagued by controversy. In 2018, a financial aid scam and a housing crisis hit Howard University, which has the largest endowment of any historically black college. Morehouse College, another member of the “Black Ivy League,” completely dismantled its leadership, including the board of trustees and its president, after a student lawsuit, a faculty outcry and an accrediting organization warning the famed institution about the makeup of its trustee board.

But everything dies.

That is why Mary McLeod Bethune, the founder of Bethune-Cookman University in Daytona Beach, Fla., suggested we invest in the human soul. A soul is an idea. A soul doesn’t die. A soul is a diamond.

But what if the investment is squandered?

How do you stop a diamond thief?

Parode: The End Begins

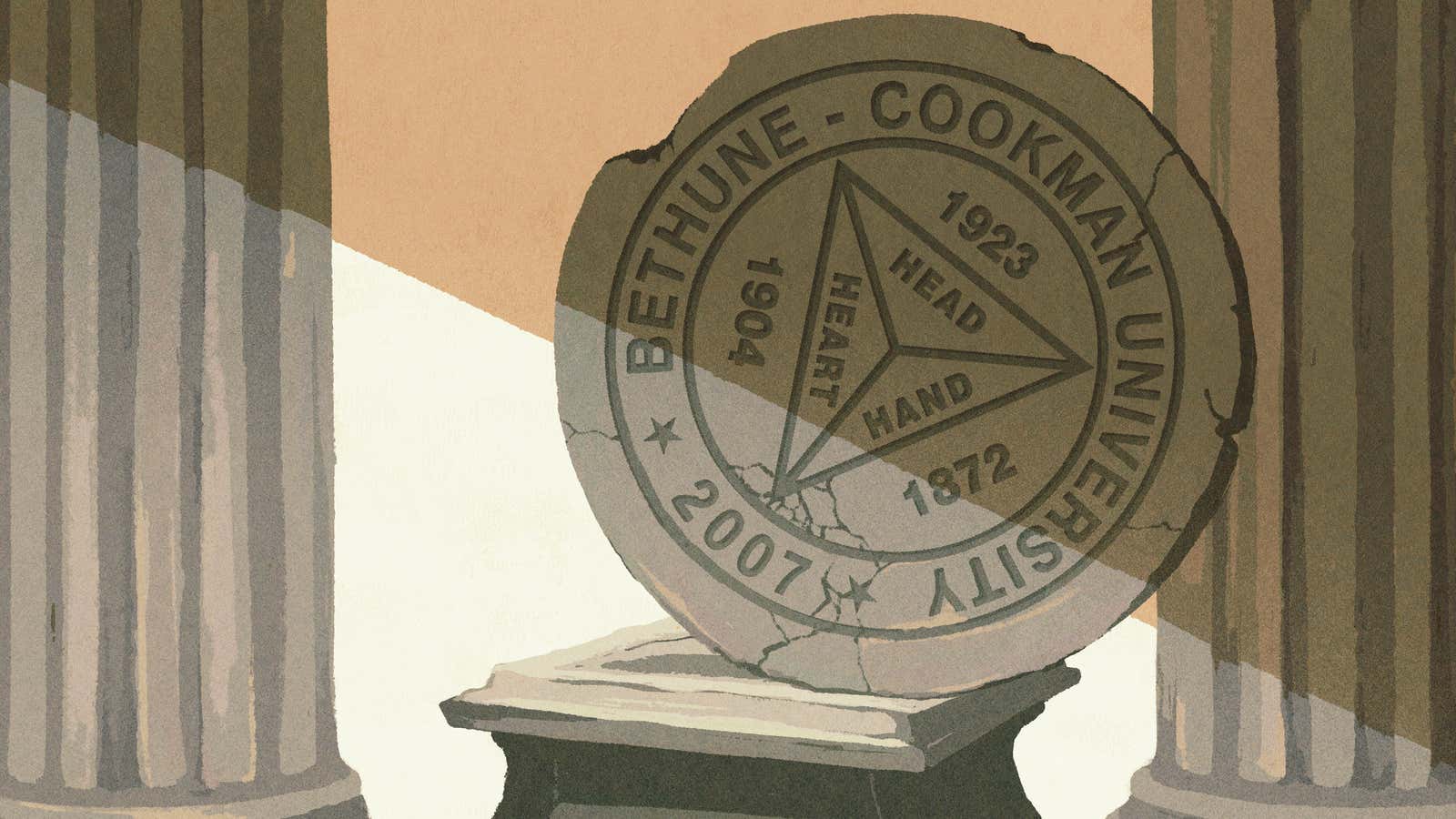

Founded in 1904 with $1.50 by Mary McLeod Bethune, the Daytona Literary and Industrial Training School for Negro Girls eventually became Bethune-Cookman University, affiliated itself with the United Methodist Church and became one of the few institutions in America dedicated to educating black students. In the fall of 2018, the school announced that the 1,177 first-semester freshmen gave B-CU its largest enrollment in history, 3,773 students (pdf).

While that may sound like an institution on the upswing, Bethune-Cookman is currently enveloped in turmoil, infighting, allegations of mismanagement and accusations of fraud that its president called an “existential threat.” No one would know better than him. But B-CU now sits on the precipice of extinction and almost every single problem is internal.

On June 14, 2018, Bethune-Cookman was placed on probation (pdf) by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC), the recognized accrediting body for universities in the Southeast United States. While SACSCOC is not at liberty to release details, the organization’s reasons for placing the school on probation read like a worst-case scenario for any educational institution. SACSCOC determined that B-CU failed to meet the body’s standards for financial resources, financial responsibility, a competent governing board and—worst of all—integrity.

But the accreditation problem is the least of B-CU’s worries. Students have also filed a lawsuit against the ex-president. In the next few weeks, Bethune-Cookman’s fate may be determined by a number of factors. The school recently announced a round of mass layoffs of faculty and staff. In October, there was a student walkout and protest. There’s the mass exodus of board members. The school reportedly defaulted on bond payments. Trustee members have been publicly accused of financial malfeasance. The chairman of the board of trustees has been ousted. The alumni president has revolted. The school may have to pay millions for a dormitory that may never be built.

Over the past eight months, The Root has interviewed dozens of people and reviewed hundreds of pages of documents detailing the maelstrom at B-CU and other HBCUs. We spoke with student leaders, faculty and alumni. What we found is a story that is impossible to unfurl in one day. The individual details that created the situation at B-CU have been well-documented but, until now, the dots have been never connected and laid out.

What follows is a modern tragedy filled with drama, intrigue and deception. As with any winding melodrama, it becomes impossible to understand the story without knowing the cast of characters and the backstory.

That is where we begin.

Act 1: The Jackson Triad

Named after noted civil rights martyr, the City University of New York’s Medgar Evers College (MEC) is often mentioned as the state’s only historically black college even though it wasn’t founded specifically for black students. It opened in 1971 as a four-year institution, but in 1986, during a period of financial turmoil and failing leadership, the Brooklyn-based school was downgraded to a two-year community college. On June 26, 1989, the City University system announced the hire of Medgar Evers’ third president, Edison O. Jackson.

Jackson, who did not respond to The Root’s request for an interview, would lead Medgar Evers for 20 years. During his tenure, Evers would experience exponential growth and become a leader on issues of justice and race in Brooklyn’s black community. Soon after the valiant knight rode into town, the school regained its four-year status and Jackson would preside over a resurgence in enrollment and growth. One of Jackson’s major accomplishments at Medgar Evers was fundraising and financing. He was a wizard at soliciting private partnerships to aid the state-funded school. He somehow found the money, waded through the regulations and delivered a state-of-the-art School of Science, Health and Technology for his beloved students.

All told, while at MEC, Jackson reportedly raised $400 million in capital campaign funds and acquired untold millions from education grants and state funding. Of course, everyone loved him. He was a hero who rescued the only predominately black college in the biggest city in America. Sure, there were always small rumors of mismanagement and scandal, according to allegations in a recently filed lawsuit (pdf), but Jackson took the criticism along with the praise. And while he was the face of MEC for two decades, he depended on the expertise and help from two men—Hakim Lucas and Emmanuel Gonsalves.

Hakim Lucas, a Morehouse graduate with a Ph.D. in education, worked for Medgar Evers teaching philosophy and religion until Jackson recognized his abilities and tapped him as the dean of the school’s Institutional Advancement Department. Essentially, Lucas became the second-in-charge of fundraising at MEC.

The person in charge of that department was Emmanuel Gonsalves. Gonsalves was an engineer and lawyer before joining Jackson at Medgar Evers. Jackson, who had an obvious eye for talent, put Gonsalves in numerous leadership roles at Medgar Evers, ultimately choosing him to serve as the vice president of institutional advancement. Like Jackson, Gonsalves would spend nearly two decades at Medgar Evers. He brought in big bucks through his strategic planning and still boasts that over 70 percent of the funds he raised at MEC came from “outside of the university system.”

This is the Jackson Triad. They made money appear out of thin air. The triumvirate is credited with raising hundreds of millions for Medgar Evers. They had the keys to the kingdom.

And then, Jackson just left.

When Jackson announced his retirement in 2009, it wasn’t a complete shock. He was a 67-year-old man who had given much of his career to educating black students. He had done the work and now he could spend the rest of his life resting on his educational bona fide. He would finally be able to ignore the whispers and rumors about MEC’s problem with vanishing money and poor management. Jackson didn’t need this. He was a hero. Even the mayor of New York said so.

Less than a year after Jackson retired, an internal audit by the City University system found a number of financial irregularities, including the mismanagement of federal grants, ineligible students receiving financial aid and employees using college-issued credit cards that, for some reason, didn’t show up on the school’s list of financial accounts.

The inquiry was so troubling that the feds from the Eastern District of New York came poking around and forwarded the information to the U.S. Department of Education. The state comptroller did a separate audit and the district attorney in Brooklyn began looking into criminal charges.

Jackson was never implicated in any of the post-departure probes but the rampant lack of oversight and pilfering resulted in the state of New York ordering Medgar Evers to repay $3.3 million (pdf) plus interest to the state’s Tuition Assistance Program. The audit only covered the three-year period ending in June 2010, so no one knows how much money the school may have received in total. But Edison O. Jackson didn’t have to worry about the residual scandals sullying his image because he was retired. He had already ridden safely into the sunset with his empire intact.

Then, Bethune-Cookman called.

As with most colleges, the Bethune-Cookman University is headed by a board of trustees responsible for the major decisions, while the president handles the day-to-day operations. Former Morehouse College President John Wilson, who is the former head of Barack Obama’s HBCU initiative, told The Root that the makeup of the board of trustees is “the most important part” of a university’s infrastructure.

Bethune-Cookman had a whopping 40 board members (most college boards average around 11.8 trustees) and the boundaries and responsibilities are spelled out in the school’s bylaws. The board appoints the president, who manages the college. At the top of Bethune-Cookman’s’s board of trustees sits its chairman. Alumni and faculty members who spoke with The Root, noted that B-CU’s board makeup had been problematic for a long time. It was bloated and packed with members who had no history with colleges, universities and—in many cases — blackness. Some of these members included:

- Leaders from the United Methodist Church, like Rev. John Harrington, a white Methodist member who would serve as board chairman from 2012 until 2015.

- Corporate leaders with no background in higher education such as Joe Petrock, a white healthcare executive who served on the board for more than a decade and would eventually succeed Harrington as board chair.

- Insiders like Michelle Carter-Scott, an alumna who had no background in higher education but was appointed to the board in 2013 after announcing that the charity created by her son, NBA legend Vince Carter, would give B-CU hundreds of thousands of dollars in scholarships. She would become board chair in 2018.

When Harrington, Carter-Scott, Petrock and the rest of B-CU board let Edwin O. Jackson take the wheel at B-CU in 2013, it was a coup. He was an experienced leader with a history of success. Like any good leader, Jackson decided to stick with what he had done before, so he called up Hakim Lucas in New York and hired him as the university’s vice president of institutional advancement.

Luckily for Jackson, Emmanuel Gonsalves was also free, having just been put on leave as president from the College of Science, Technology, and Applied Arts of Trinidad and Tobago (COSTAATT). No one still really knows what happened in Trinidad, but Gonsalves was reportedly escorted from the COSTAATT campus by security and multiple Trinidadian news outlets reported that “an audit has been ordered into all operations at COSTAATT with a directive that prohibits the shredding of any documents at the school,” adding: “Increased security has been ordered at the school to ensure no documents are taken from the compound.”

When Gonsalves heard that Jackson was putting the band back together again in sunny Florida, he resigned his COSTAATT presidency and went to work for B-CU as Jackson’s consultant. In a matter of weeks, Gonsalves would be named Bethune-Cookman’s vice president for finance and strategy.

Allow us to reintroduce the Jackson Triad 2.0.

This time there would be no city university system oversight. Bethune-Cookman is a private, nonprofit institution so there would be no state auditors breathing down the emperor’s neck. Jackson didn’t have to dig the school out of a financial hole. This time, Jackson had complete control of everything. With Lucas in charge of fundraising and Gonsalves serving as the chief financial officer of Bethune-Cookman, who could stop them from turning their wildest dreams into reality?

So the newly crowned king Edison O. Jackson sat on the shiny throne of his 108-year-old kingdom, surveyed his kingdom and—finding it wanting—decided to build himself a castle.

Act II: The Deal of a Lifetime

One of the many problems at cash-strapped HBCUs is the need for housing. A few years after Jackson took over at B-CU, the school badly needed dormitories. The existing dorms were old and infested with mold. An increase in enrollment after Jackson became president forced the school to rent hotel rooms for almost 900 students. So, in 2015 ,Bethune-Cookman and President Jackson announced plans to build a 110,000 square-foot building for the low price of $72 million. Although the price seemed high, experts say it was not unreasonable. The great news was that B-CU wouldn’t have to fork over a dime for this beautiful new facility.

Jackson had done it again. The deal was almost too good to believe.

According to a presentation to the B-CU board of trustees obtained by The Root, the building would include a student center, housing and retail space. The university wouldn’t have to put up a penny to have this state-of-the-art facility because it would be built and financed by two connected companies—Quantum Realty and TG Quantum. Controlled by Darnell Dailey, the Quantum companies were “highly experienced in real estate development and in the management of real estate assets,” according to the presentation.

The Jackson Triad convinced the 30-plus members of the board of trustees to lease B-CU’s land to Quantum, who would then construct the building and allow the school to rent the building. The presentation stated that the income from the retail space and student housing would supposedly pay for the loans and leave B-CU with a healthy profit. Dailey even agreed that Quantum would generously donate $1 million per year for three years to B-CU and, to top things off, because of the private financing, the $72 million-debt wouldn’t affect B-CU’s credit rating.

There was one slight problem with the much-anticipated dorm:

It was never going to cost $72 million.

On January 22, 2018, Bethune-Cookman filed a civil complaint in a Volusia County, Fla. circuit court (pdf). According to internal documents acquired by The Root, Dailey didn’t disclose that the proposed facilities wouldn’t contain a student center. Or retail space. And there was another slightly bigger problem. According to the suit, Dailey and his partners also hid the fact that the entire project was priced at $84 million.

The details of the swindle involve millions of dollars, a possible forgery, a bait-and-switch and a shell corporation bearing Bethune-Cookman’s name. The lawsuit describes how Dailey, his companies and his co-conspirators reportedly colluded to defraud Bethune-Cookman out of millions. It even lists the names of the cabal of con men. The list includes Dailey, described as the salesman and “front man”; Mark Glover, the mastermind; TQ Quantum; Quantum Realty Capital and Allied Strategic Partnerships.

The civil complaint also accuses three individuals of conspiring to breach fiduciary duties and with engaging in constructive fraud. It also brings a count under Florida’s Civil Penalties for Criminal Practices asserting that the defendants committed felonies of commercial bribery. As the plaintiff, Bethune-Cookman asked a jury to levy triple damages against the three men who were accused of orchestrating this scandal from “behind the scenes.” All were able to get away with no criminal charges thus far.

One of the alleged conspirators left Bethune-Cookman and became the president of Virginia Union. His name is Hakim Lucas.

Like he did at COSTAATT, Emmanuel Gonsalves, who presented the details of this whole dorm idea to the board of trustees, left before the shit hit the fan. He found another, more lucrative job—with Darnell Dailey.

Neither Dailey, Lucas nor Gonsalves have responded to The Root’s requests for interviews.

Because of the dorm deal, the university defaulted on a bond agreement, which stipulated the amount of debt that the school could incur. The university was also sued by the financiers of the dorm deal. So despite the Jackson Triad’s assertions, the school’s credit rating, debt and educational status were all affected by the deal. And as he once did with Medgar Evers College, the key member of the Jackson Triad “retired,” galloping into the sunset just before the federal investigators came in.

When Edison O. Jackson resigned from Bethune-Cookman, the board, students and faculty had recently discovered the actual price for that new-state-of-the-art student housing with an invisible student center and zero retail space was not $84 million.

It was $306 million.