If there’s a fault that Deion Sanders should own as he leaves Jackson State University for the University of Colorado—and one that’s earned him the most smoke from his critics—it’s that he was always an HBCU short-timer who held himself out instead as a savior, or at minimum a zealot for the institutions, their mission and the uplift of their athletic departments.

Those departments, like the institutions themselves, have largely existed in two eras: a segregated one in which they were awash in the best Black talent the country had to offer because that talent was limited by law, custom and deeply-rooted bigotry, from shopping itself elsewhere. The second came in the 1970s and since, and has been marked by predominantly white institutions, or PWIs, figuring out that that talent was more valuable than segregation, and using their resources to create a system where HBCUs could no longer compete for the same players that PWIs once shunned.

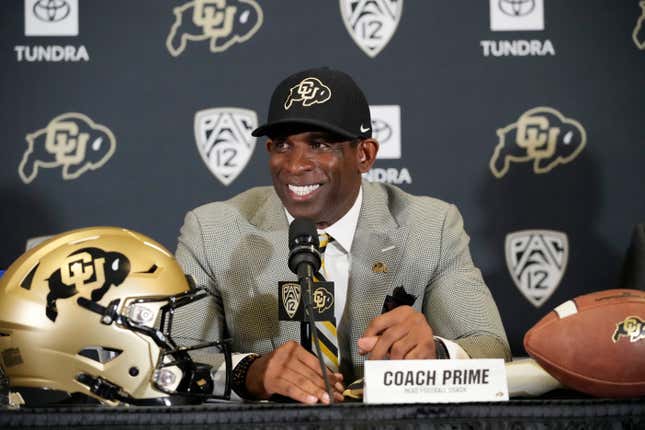

Coach Prime walked into that dichotomy loudly and willingly when he took over head coaching duties at Jackson State University in 2020, proclaiming then and many times since that his goal was leading HBCUs into a third era. Schools like Jackson State and others in the Southwestern Athletic Conference would do business a new way, bring in more revenue, attract new media deals and donors and ultimately mean they could compete for homegrown talent—our kids—again. If there was anyone who could elevate programs like JSU, he told us, it was Coach Prime, a Hall of Famer with Southern roots and a unique voice, perspective and approach who was uniquely suited to deal with deep and novel challenges of running a perpetually under-resourced shop.

In some ways, he wasn’t wrong and deserves credit. As a player, Sanders was a constellation among stars, so valuable that teams in two sports tolerated having access to him more or less on a part-time basis. As a coach, he brought attention and clout that maybe no other HBCU coach ever had. If your defense of Deion Sanders today includes that fact that without him, JSU’s Tigers don’t sell out games, attract ESPN’s College GameDay for a live broadcast and aren’t building a new athletic facility, you’re not wrong.

But that’s also why the “He Ain’t SWAC?” beef between Sanders and Alabama State coach Eddie Robinson Jr. was so strange to me: Of course Sanders was never truly SWAC, which is to say he was never anything like the hordes of coaches, administrators or professors who have made careers out of doing the real work of HBCUs: readying Black professionals, entrepreneurs and intellectuals to compete and lead in an overwhelmingly white and often hostile world. Most of those people toil in an obscurity Sanders will never know. His fame and resume brought five-star recruits, new donors and cameras to the yard and none that would have materialized if Sanders were a creature of the SWAC or of HBCUs to begin with. Sanders’ success at JSU was of the type that only comes with being an anomaly.

And now that that anomaly is headed to Colorado, there are already signs that what many of us feared would happen—that Sanders’ success was only a temporary phenomenon, not a paradigm shift—is already happening. Three recruits—receiver Robert Lockhart III, offensive lineman Jordan Hall and defensive back Twan Wilson—have all decommitted from playing at JSU since Sanders’ announcement on Saturday. At least two of them had offers from larger “Power 5" schools but chose JSU because of Sanders’ decision. Sanders has already said he plans to take as many as 10 of the top recruits he lured to JSU, along with his son, quarterback Shedeur Sanders, to Colorado with him. It’s safe to assume he’ll do the same with some assistant coaches, like former NFL head coach Mike Zimmer, leaving JSU with the same hole for talent on the field and on the sidelines that it had before Sanders was hired.

It might help a little that Sanders has to pay back about $300,000 of his Jackson State contract under terms of the deal, but with the millions he’s getting from Colorado, he probably sent that Zelle from his flight out of Mississippi.

Jackson State is also left to deal with a lawsuit from the organizers of the Southern Heritage Classic football game, which Sanders said he was pulling JSU out of after playing in the game for 30 years, two years before its contract with the organizers ended.

“It’s a hustle,” Sports Illustrated quoted Sanders telling the Pardon My Take podcast months ago. He argued that HBCUs were being played like fools and not getting a respectable return for what they were giving the organizers in return.

“The first thing we need to take care of as HBCUs is the business aspect of everything, and that’s something we’re changing right now. We’re taking care of business.”

It’s a hustle, indeed. And now it looks like those of us who hoped Sanders might have made a longer commitment to Jackson State need to get back to focusing on the business aspect of our own schools.