Some of us have always felt in the pit of our stomach that Francis Scott Key’s “The Star-Spangled Banner” is a tad too, well, American-y. Fortunately, we’ve always had “Lift Every Voice and Sing” — known colloquially as the “Black National Anthem” — as a fallback to acknowledge love for a home that hasn’t historically loved us in return.

Entire books have been written about the history of the Black National Anthem. But as we prepare for Grammy Award-winner Andra Day to bring the house down by performing “Lift Every Voice” alongside country singer Reba McEntire performing “The Star-Spangled Banner” at Super Bowl LVIII on Feb 11, here’s a bit of background on our song.

Children were the first to perform the song

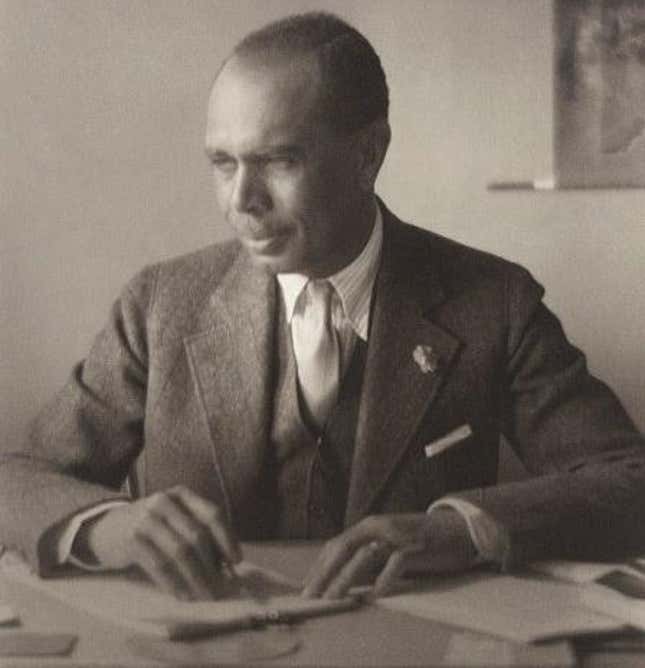

Brothers James Weldon Johnson and John Rosamond Johnson wrote and composed the song in 1900. James started it as a poem to commemorate the birthday of President Abraham Lincoln before it morphed into a poem about the struggle of Black folks in the throes of Jim Crow, which he asked his composer brother John to set to music.

As the principal of a segregated school in Jacksonville, Fla., James had his 500 of his students perform the song publicly for the first time. Through the mouths of babes in schoolyards and churches, the anthem spread in subsequent years, and the NAACP named “Lift Every Voice and Sing” its official song in 1919, a year before James became the organization’s first Black executive secretary.

“The Negro National Anthem” became the “Black National Anthem,” and the rest is Black history.

At least one artist you love has performed it

If you enjoy Black American music even a little bit, then someone you adore has likely performed “Lift Every Voice” at some point.

Melba Moore’s 1990 version likely included at least a couple of artists you love: Stevie Wonder, Dionne Warwick, The Clark Sisters, Freddie Jackson, Anita Baker, Bobby Brown (!), Howard Hewitt, Take 6, Stephanie Mills, BeBe & CeCe Winans and Jeffrey Osborne all get busy on the nearly 6-minute version.

Of course, Beyoncé brought the song out of cultural dormancy and introduced it to a host of younger souls to the song when she performed it during her legendary 2018 Coachella set.

White people are still tight about it 120 years later

Because we can’t have a damn thing of our own, white people (and their nonwhite sycophants) still view “Lift Every Voice” as a symbol of division. “Why can’t we all unite under just one anthem?” query the mouth breathers with their diet racism.

When the estimable Sheryl Lee Ralph performed the song at last year’s Super Bowl, then Arizona gubernatorial candidate (and bootleg white lady) Kari Lake went viral for sitting down during the performance. Later that year, Lake tweeted her complaints about the NFL allowing a youth choir to perform the song at a game.

Doing your googles will unearth no small number of folks who consider “Lift Every Voice” racist, even though “Banner” was written at a time when we were still enslaved and became the official national anthem in 1931, when we couldn’t legally sit with white folks in the south.

Should it surprise anyone that the same folks bitching about our anthem have nothing to say about the scores of “Banner” clones that are still performed to this day? No…it should not.

It experienced a renaissance moment after George Floyd’s murder

If Kendrick Lamar’s “Alright” became the unofficial Black Lives Matter theme song following the murder of George Floyd, “Lift Every Voice” saw more of a formal resurgence in the wake of the unprecedented global protests in 2020.

The NFL had it performed before every season opening game in 2020. Surprisingly, even NASCAR got in on it.

President Joe Biden even leveraged the song title around this time for his “plan for Black America…” Which…I guess.

Lots of Black people thought everyone’s sudden desire to use the Black National Anthem was pandering, which isn’t beyond the pale when you consider how many non-Black-owned businesses put “BLM” on their storefronts only to avoid getting looted.

However, we recognize when the song is utilized authentically: Grammy winner (and Root 100 honoree) Jon Batiste performs it every chance he gets, including playing it as bandleader on “Late Show With Stephen Colbert” or during peaceful New York City protests in 2020.