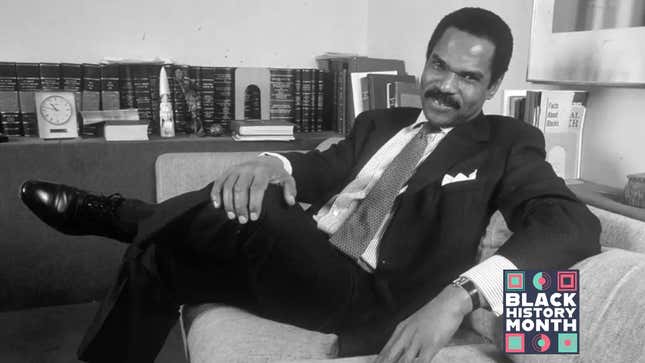

Reginald F. Lewis may not be well-known to millennials, and that’s a shame because his life and work is black excellence personified. His rich legacy of entrepreneurship and possibility lives on to this day.

How appropriate, then, that his life is being memorialized in a PBS documentary, Pioneers: Reginald F. Lewis and the Making of a Billion Dollar Empire, during Black History Month. Lewis, before his untimely death in 1993 at age 50, seemingly made black history at every turn.

Lewis was the first African American ever to close an overseas leveraged buyout deal for $985 million. In addition to being the first black billion-dollar deal-maker, Lewis was the first African American to open a law firm on Wall Street; the first and only person to be accepted to Harvard Law School without applying; and one of the first black men in America to have a museum named after him: the Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History & Culture, in his native Baltimore.

Geraldine Moriba, executive producer of the documentary, said that one thing that surprised her about Lewis was how so many people who didn’t know him credit him with being a stark influence on their lives.

“People who’ve never met him and have no direct connection to him or any of his businesses have said to me they would not have gone into business or finance or banking if they had not heard his story,” she says. “And I heard that again and again and again.”

Lewis is what we now call a “serial entrepreneur” who started his first business at the age of 10 (a newspaper business where he had other children working for him, AND which he sold at a profit some years later). After attending the prestigious Dunbar High School in Baltimore, where he was a star quarterback, he went on to attend an HBCU, Virginia State University, on a football scholarship.

In his senior year, Lewis attended a summer program at Harvard Law funded by the Rockefeller Foundation and excelled to such an extent that at the end of the program, he was invited to attend the law school, the only person in the school’s 148-year history to be admitted before applying. Within two years of graduation, he started his own law firm, focusing on corporate law, and, according to a biography on the Lewis Museum’s website, “helped many minority-owned businesses secure badly needed capital using Minority Enterprise Small Business Investment Companies (venture capital firms formed by corporations or foundations, operating under the aegis of the Small Business Administration).”

Loida Lewis, Reginald’s widow and an incredible businessperson in her own right (she took over his business a year after his death and turned it around within one year), says that this was the right time for his story to be told. “It’s been many years, so anyone under 40 would not have heard of Mr. Lewis. They should know that an African American man accomplished so much. Always pushing the envelope,” Loida says.

“His legacy, he said it himself, was ‘Keep going no matter what,’” she adds. “Not that he didn’t have any failures; he had many failures. But he kept going.” She says that after her husband left Harvard Law and joined a prestigious law firm, they told him after two years that he wasn’t going to make partner. But he didn’t let that stop him. He founded his own law firm and went on to make history with the deals he made, though she noted that he failed three times before his first big one—but that he learned from each of those failures.

Reginald Lewis’ first successful deal was a $22.5 million leveraged buyout of the McCall Pattern Co., which he nursed back to health and led to the two most profitable years in the company’s 113-year history. In the summer of 1987, Lewis sold McCall, making a $50 million profit.

Next up was the deal that made him famous. The museum explains:

In October 1987, Reginald purchased the international division of Beatrice Foods, with holdings in 31 countries, which became known as TLC Beatrice International. At $985 million, the deal was the largest leveraged buyout at the time of overseas assets by an American company. As Chairman and CEO, he moved quickly to reposition the company, pay down the debt, and vastly increase the company’s worth. By 1992, the company had sales of over $1.6 billion annually, and Reginald was sharing his time between his company’s offices in New York and an office in Paris (most of the company’s businesses were in Europe).

Loida Lewis, who describes her late husband as “very dynamic, very intesnse, very driven, very ambitious and very hardworking,” also noted that as a husband and father (they had two children together: Leslie and Christina), he was “very loving, very tender, very sensitive.” She admitted that he had a legendary temper but that he always made amends if he offended.

These days, Loida spends time with her grandchildren in her lovely home on New York City’s Upper East Side, which is filled with glorious art, including Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence and a Picasso, and brags about her two daughters, both of whom also went to Harvard. The oldest, Leslie Lewis, is an actor who created a play called A Miracle in Rwanda, about a woman saved from the massacre in Rwanda. Her youngest, Christina Lewis Halpern, created a nonprofit, All Star Code, that trains black and brown boys to code during the summer.

“So in their own way, they’re continuing Mr. Lewis’ legacy,” says Loida, who notes that Reginald was also a great philanthropist.

The Reginald F. Lewis Foundation, founded the same year he made the TLC Beatrice deal, gave an unsolicited $1 million to Howard University. In 1992, Reginald donated $3 million to Harvard Law School—the largest grant in the history of the school at the time. In gratitude, the school renamed its International Law Center the Reginald F. Lewis International Law Center.

For Moriba, Reginald Lewis’ legacy was making what seemed impossible into reality.

“I think his legacy is that he opened doors and he created hope where it didn’t necessarily exist,” Moriba says. “He became a model of how to be successful and made it real. That’s his legacy.”

The film streams nationally at wliw.org/pioneers, thirteen.org/pioneers and njtvonline.org/pioneers and on Thirteen Explore OTT apps.