I know Bakari Sellers.

Before I even read his upcoming memoir, I knew his life story like the back of my hand. We’re practically cousins. We were both raised in eerily similar South Carolina towns. Sellers grew up in Denmark, S.C., where my family briefly ran a small diner where people regularly ordered “liver pudd’n”—a South Carolina breakfast delicacy that pops off the short-order grill like hot grease (I still have the scar on my wrist to prove it). Our childhoods were almost mirror images of each other.

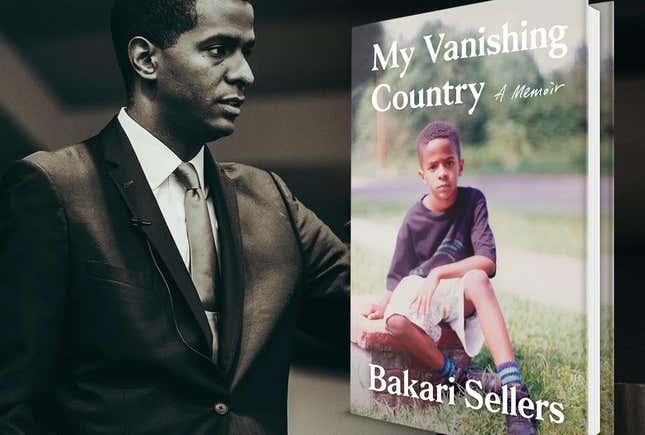

Our families know each other. My uncle James often spoke of Sellers’ father—civil rights hero Cleveland Sellers. In fact, when I interviewed him about his upcoming memoir, My Vanishing America, the first question he asked was about my aunt Jannie, whom he said had “more institutional knowledge than anyone you can imagine.”

Of course, “how your peoples doing?” is an old Southern greeting that predates either of us. Even if I had not spent a summer cooking liver pudd’n in that tiny restaurant in Sellers’ hometown, he would be obliged to ask. Where we’re from, it’s the law.

I have never met Bakari Sellers.

Ever.

When Bakari Sellers made history at 22 years old by defeating a 26-year incumbent to win a seat in the South Carolina House of Representatives, I had already escaped the Carolinas. When I volunteered to work on a grassroots campaign for some long-shot senator from Illinois named Barack Obama, I heard that the state steering committee was headed by a wunderkind on the political scene and wondered if “Bakari and Barack” was a new sitcom premiering on UPN or an elaborate plan to secure the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination by scaring white South Carolinians to death.

But a lot of black people know Bakari Sellers and his story. It has nothing to do with the fact that he served in the South Carolina legislature as the youngest African-American elected official in America. My familiarity with Sellers has nothing to do with his CNN political commentary or his run for S.C. lieutenant governor. There is another reason altogether:

Bakari Sellers’ story is black America’s story.

All those biographies and novels about the poor negro escaping the impoverished inner-city ghetto to gain fame and success are not indicative of most black lives. While the word “urban” has somehow become synonymous with black, the largest concentration of black people live in the South, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Of the 106 majority-black counties in America, only one — St Louis, Missouri—was not in the Southeast United States. And, like Sellers’ hometown, most of these blackity-black places are not metropolitan areas.

“I want people to understand that to be a country boy and country folks, um, does not mean that you’re ‘backwoods’ or less sophisticated,” Sellers told The Root. “I think that the black cultural liberation ideology that we see throughout this country stemmed from people in the Deep South. And, to put it bluntly, the media in particular, when they say rural, they mean white people. They mean Gretchen Whitmer and Amy Klobuchar. But I’m rural and you’re rural, too! The Black Belt is our roots. I mean that literally —that soil, the richness of that dirt road that we grew up on, those are our roots. And the plights that we go through have, many times, been forgotten.”

It is impossible to discuss Bakari Sellers, his life or his activism without discussing his father, a civil rights leader and a one-time political prisoner.

Two years before National Guardsmen killed four white Vietnam War protesters at Kent State University in 1970, South Carolina State Troopers opened fire on black students from S.C. State University who were protesting a segregated bowling alley. Although the Kent State shooting has become infamous, the Orangeburg Massacre not only resulted in three deaths, but provided American history with a pristine example of white supremacist justice in the South.

As Sellers outlines in his memoir, after years of working as a civil rights activist with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Bakari’s father, Cleveland Sellers, was one of the student leaders who was shot at the SCSU protest. The case marked the first time in history that police officers faced a federal trial for excessive use of force at an HBCU.

All nine officers were acquitted.

The officers claimed they were in danger because the students were firing at them. Aside from the troopers’ guns, no weapon was ever recovered nor has any eyewitness ever testified that they saw or heard a student use a firearm on that day. However, one person did spend time in prison because of the massacre:

Cleveland Sellers.

My Vanishing Country makes it clear that Sellers has never tried to outrun the darkness of his father’s long shadow. Instead, he casts his entire life as an attempt to provide his father a semblance of freedom from his status as a political prisoner as well honoring his mother’s strength.

“Everything I do, I live to complete the legacy of my father,” said Sellers. “I live for my twins. I live for Michael Brown. And that’s what gets tiring sometimes. And the reason that I do that is because it’s just like Julian [Bond] and Marion [Barry] and my dad would say. They would always talk about the fact they were living for Emmett Till. They were, they were living for Medgar [Evers], Jimmy Lee Jackson. And so that is, that is the way that I live my life. And it gets tiring, but it’s an awesome and fulfilling kind of journey.”

Sellers recounts his mother almost dying as she gave birth, highlighting the pervasiveness of maternal health issues in rural communities as well as honoring her strength as she endured decades of persecution, poverty and indignity in South Carolina. He contends that the stress of living through the movement and being a black man in the rural South is as hereditary as any diagnosable illness.

“My father was shot and ripped away from our family,” Sellers explained. “And my mother had to carry and give birth to a child [Bakari’s oldest sister] while her husband, my sister’s father was in prison. That trauma still lives with us today. Trying to provide for a family, living through that stress, having that sense that, that felony on your record.

“Sometimes when I look at my father today, you can understand why you’re so weary and tired — because you fought so hard,” he noted, adding: “And so for any of us who were children of the movement, we have to fight just as hard. And our mental health, our anxiety, the struggles we have, a lot of them are brought about through many of the struggles we’ve had and we have to lean into those things and overcome them just as the generation before us.”

So how does he reconcile his father’s rebellious past with his decision to work inside the belly of the beast? Perhaps the most evident lesson in My Vanishing Country is Seller’s lack of naiveté about what America is. Even with his time inside the institution that tortured his family, he was under no illusion about his country and his state’s past and present.

“In the book, I talked about moments when I would walk up those steps and be like: I’m about to go in here and fuck this shit up’” Sellers said, adding: “That was my way of being the ultimate change maker. That was the way that I was going to ultimately allow my father to be free. The way I was going to fight for my father’s freedom and the freedom whatever family I would have in the future, was going to be able to go in this body which had persecuted my family and created injustices— the remnants of which we still live with today.”

He continued:

And this is the tragedy of this all for black folks who would see any semblance of justice...freedom or peace. Unless there is blood spilled by people of color, we can’t be free. That’s why the lady of justice, the blind lady of death, holds a scale. We literally have to pour our blood on one side for it to be equal. And that’s a painful realization.

Those dusty Denmark roads still inform Sellers’ every decision, a fact that makes him both proud and defiant. Even as the America that raised him slowly dissipates, he still believes it is salvageable. Sellers’ story is as relevant to the narrative of white “economic anxiety” or “urban” America. This America belongs to him, too.

“I’m like the white boys were protesting out there in 2010,” Sellers noted.

“I want to take my country back.”

My Vanishing Country: A Memoir is available for purchase.