I am 6.

I am sad because my face is black and not striped.

My sisters and I are at Kalmia Gardens, the beautiful home of Thomas Hart, who founded my hometown, Hartsville, S.C., in 1817. Every year, we visit the Kalmia Gardens Festival and every year, my mother forbids us from having the local artists paint our faces, which saddens me.

It’s not like they paint our faces white. I am obsessed with tigers and I desperately want some tiger stripes painted on my face but my mother says no.

Mama’s not even here! This is a Vacation Bible School trip and—even though my mother knows the Bible like the back of her hand, she never takes a vacation. But my oldest sister Sean is in charge, and Sean does not break the rules. Sean won’t even allow me to even go to the little house where they paint the faces. It’s so small and pretty, it’s almost like it was made for children. Like a dollhouse. I always wanted to stay there, even though I couldn’t go inside.

I beg.

Sean says no.

She is as inflexible as my mother.

Every small Southern town has their own version of the Kalmia Gardens Festival that celebrates the history and the tradition of the area. Darlington, S.C., the city adjacent to my hometown, calls theirs the Sweet Potato Festival. Lamar, S.C., has the Egg Scramble. McBee has the Peach Festival. They usually take place at a bucolic location like the plantation home in Kalmia or the town square in Darlington. I’ve been to them all, but to this day, I still haven’t had my face painted at Kalmia Gardens Festival. I still haven’t even gone into that small cabin even though most of my childhood friends have this shared common experience. They probably don’t even consider it a privilege to frolic in the face-painting dollhouse.

Or as it is technically called...

The slave quarters.

America hates us.

The notion that America whitewashed its history is a somewhat abstract principle to most people because America’s education system avoids the reckoning that comes with learning the truth. The maliciousness is not just about statues and school names. This seemingly innocuous oversight actually causes many of the economic, political and social disparities that persist in one of the richest countries on earth.

Perhaps the reason that the prospect of reparations is, for many, an outlandish idea, is because we are not truly educated about the devastating effects of slavery, Jim Crow or white supremacy in general. Every institution in this country treats America’s foundational racism as though it is a stain on the American fabric that we have since washed clean. So the racial wealth gap remains. School inequality remains. Police brutality remains.

After all, why would anyone go out of their way to fix a country that was never broken?

In May, Ursula Harris helped her daughter with her history homework and discovered that a fourth-grade teacher at Bradley Elementary in Columbia, S.C., had tasked each student with writing an essay on whether they’d prefer to be a slave or a slave owner.

“I was so mad I was shaking,” Harris told WISTV. “My baby was like momma its okay. I had tears in my eyes.”

This is not unusual. Black fifth-graders in Bronxville, N.Y., were forced to portray slaves while their classmates bid on them in a mock slave auction. It happened in Virginia, too. And New Jersey. California’s Whitney High School put their eighth-graders on an imaginary slave ship. It happens all the time.

To be black in America is to ingest the historical hate that this nation has shown to black people. Not only must we consume it, but we are also expected to smile while swallowing the rancid meal that this country force-feeds us. We are expected to honor the brutality. To herald our oppressors as heroes.

We must love the thing that hates us.

I am 11.

I am happy.

I am technically a runaway.

My uncle Junior gave me $20, so my cousins Tyran, Derrick and I take off from my aunt Jannie’s house in East Orange, N.J., where we spent the summer.

We are going shopping. Tyran buys gummy bears. Derrick (We called him “Geet”) buys fat shoelaces for his Adidas. I spot a replica of a car from one of my favorite television shows and immediately know that’s what I’m going to buy. The cashier looks at me as if I am crazy but sells it anyway. I am happy. We walk to Newark to my Uncle Rob’s (Geet’s dad) ninth-floor apartment.

The house is filled with Uncle Rob’s shady friends. Tyran shows his gummy bear haul. Derrick strings up his Adidas. I do not show my Hot Wheels car because I already know, for some reason, everyone in my family hates that car. Even my Uncle Rob won’t let us watch it and he sells cocaine.

Hours later, after driving around for hours searching for us, my Aunt Jannie bursts through the door with tears in her eyes to inform my Uncle Rob that his son and nephews have been kidnapped. She turns around and discovers us. She is relieved. But her relief soon turns to anger when she discovers the newest addition to my Hot Wheels collection. She snatches it from my hand and throws it out the window. She could have killed someone.

And that’s how I lost my replica of The Dukes of Hazard’s General Lee.

I am not happy.

When members of the South Carolina African American Heritage Foundation, charged with creating a more representative Black history curriculum, confronted the officials at the South Carolina Department of Education, Stephen J. Corsini, the Social Studies Education Associate in the SCDOE Office of Standards and Learning responded with a shrug.

“Nowhere in our 2011 standards or support document or in the 2019 standards or alignment guides do we suggest students pretend to be a member of enslaved populations or any marginalized groups.,” Corsini wrote in emails obtained by The Root. “This was a local decision made by individuals in that school district. The activity, upon looking at the image provided in the news media and that observation alone, appears to be purchased and not properly vetted.”

Another parent, Bobby Donaldson, didn’t think Corsini’s explanation was enough, writing:

I assume “nowhere in our 2011 standards or support document or in the 2019 standards or alignment guides” is it recommended that our third grade son bring home a social studies assignment on “Eli Whitney’s Cotton Gin” WITHOUT ONE reference to enslavement and the brutal exploitation of black people that intensified after “Whitney’s invention.” Instead our son reads: “However, picking cotton was hard work. Men, women, and children stooped over the cotton plants into the fields all day long.” “A single one of Whitney’s machines replaced a back-breaking day’s work of many people. The most difficult and slowest work of cotton plantations became much easier and faster.”

And then the assignment carried the attached photograph, clearly depicting African people. The caption reads: “Everyone seemed to want to have a cotton farm after the invention of the cotton gin.”

Needless to say, our son was re-educated.

When I was 12, my football coach dimmed the lights in his history class and showed us a slideshow of his weekend activities—fighting on the “Gray Side” in Civil War reenactments. My other football coach married my Advanced Placement U.S. history teacher. In that AP U.S. history class—the most advanced high school history course in the state of South Carolina—we didn’t talk about slavery, even though my teacher was a bonafide Civil War historian. I was mostly quiet during our study sessions at their beautiful home, which was decorated with Confederate memorabilia.

Donaldson knows the whitewashing of America’s history. He has made it his lifelong fight to correct it, which is why he sits on the board of the SCAAHF. But that is not his main job.

Bobby Donaldson is also a history professor and the director of the Center for Civil Rights History and Research at the University of South Carolina.

I am 18.

I am not happy.

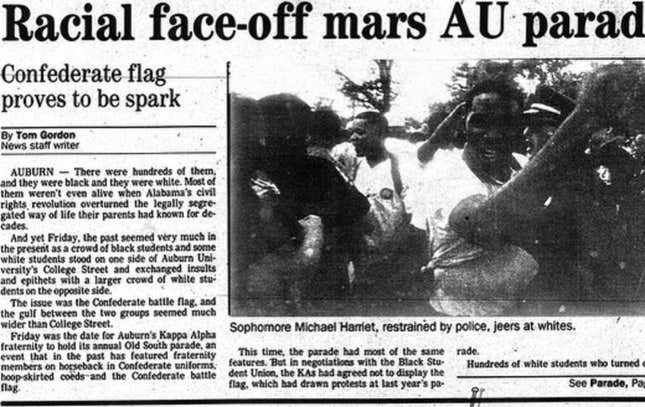

I am being restrained by police.

For years, the Black students at Auburn University have protested Kappa Alpha Order’s “Old South Parade,” a tradition that happens on college campuses where members of one of the oldest American fraternities celebrate the Confederacy. Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee did it when he was a member. South Carolina Gov. Henry McMaster did it when he was a member in college. So did Rep. Joe Kennedy III (D-Mass.), Roy Blount (R- Ala.), Former FBI director J. Edgar Hoover and former Carolina Panthers owner Jerry Richardson, among many others.

The parade was notable for its use of racist imagery, especially the Confederate flag.

People had protested the parade before. Weeks earlier, George Smith, a former student who attended Auburn 20 years before that day, told me how he and his friends climbed a flagpole and removed the Confederate flag during an Auburn football game. That was why the school stopped flying it.

I move past the protest barriers that were set up by the city and step out in the street in front of the parade. Police grab me. Other students cross the line and sit down in the street.

That was the last Kappa Alpha Old South Parade at Auburn University.

Kappa Alpha’s history is interesting because it is important to the spread of the mythology of the “lost cause.” The Southern fraternity is actually a reboot of the Original Kappa Alpha Order, formally known as Kuklos Adelphon or “Circle of Brothers,” which was disbanded in 1855 and reorganized after the Civil War. But even during the gap in the fraternity’s existence, it didn’t totally disappear because another, non-college organization adopted the K.A. ritual verbatim. The new group didn’t go to college, so they didn’t care about the greek letters. So they slightly modified the name Kuklos and added a word that symbolized their family ties.

They called themselves the Ku Klux Klan.

The next day, there was a picture of me on the cover of the local newspaper. The caption read:

“Sophomore Michael Harriet, restrained by police, jeers at whites.”

The South Carolina African American Heritage Foundation responded to the SCDOE’s lack of action with a statement, which read in part:

Such a dismal failure on the part of the school district’s personnel helps to explain why for years, South Carolina’s public-school system has continually ranked one of the worst in the nation. Perhaps because most of the children who are victims of this sorry state of affairs are Black, Brown and poor, the mostly white powers-that-be in the state simply don’t care. They send their children to private schools or live in wealthy mostly white school districts with major resources. Meanwhile, poor majority Black districts in rural areas like those in the Corridor of Shame along Interstate 95 languish in mediocrity. Our “minimally adequate”educational system produces students who are handicapped bylow expectations, apathy, scant resources and the least qualified personnel who are often just working for a living and are indifferent or even hostile toward the population they are supposed to be serving

For its part, the state Department of Education passed the buck.

“The state does not assign curriculum which encompasses homework assignments and classroom activities,” state Department of Education spokesman Ryan Brown said in an email to the media. “Slavery is covered extensively in state social studies standards, but we do not prescribe how those standards are taught.”

Our children must not be given assignments that will marginalize them or make them feel inferior. They look up to their teachers and generally would not question an assignment.

“As a former educator and chairperson of the South Carolina African American Heritage Commission, an organization that provides resources in social studies for South Carolina’s educators—resources which often are not used or used properly—I am appalled at this incident and how somebody dropped the ball,” the statement continues. “We cannot afford to have people dropping the ball where the education of our children is concerned.”

That statement was drafted by the chairperson and founder of the SCAAHF. She is a Black woman. She does not play about history. I wouldn’t even call her a “nice lady” and I know her well. Of course, I may be prejudiced because I still hold a slight grudge from when she tossed my General Lee Hot Wheels out of a ninth-story window.

Her name is Jannie Harriot.

She jeers at whites.

I am 38.

I am happy.

My aunt Willa Mae is telling the tale of my family, which began when my great-great-great grandfather Earvin was tossed off a Sumter County plantation for teaching enslaved Africans how to read and write. He was always trouble. When Earvin’s owner, John, died, he left dozens of slaves to his children. But in the last paragraph of the will, John wrote:

“My negro man Ervin is to have his own time so far as consistent with the laws of the State—he is not to be appraised when my estate is valued and no other services are to be required of him.”

But Earvin kept jeering at whites. He managed to buy his own property and he somehow sold more tobacco than anyone in Sumter County. The white farmers eventually stopped Earvin from selling tobacco, so he went to neighboring Darlington County to sell his harvest.

But Earvin wasn’t a farmer, he was a teacher and a blacksmith.

In the mid-1800s, Earvin would go onto Sumter County plantations to preach and teach enslaved children how to read. It turns out, the enslaved people would pay Earvin by stealing small amounts of tobacco from their owners’ farms and giving them to Earvin. And, because many of the plantation owners were fighting in the Civil War, the people who were running the plantations didn’t know they had been missing crops.

After the Civil War, Earvin continued to teach but he still had to go out of town to sell his crops. One day, at the Darlington County Courthouse, everyone was gathered to get their tobacco stamps, which essentially allowed them to sell their crops or trade the stems for other goods. The white men, suspicious of how many stamps Earvin needed, “seized upon” Earvin and his grandson, Earvin Jr. They took all of their tobacco stamps and killed Earvin.

Earvin Jr. managed to get away.

Earvin Jr. is my grandmother’s father.

And that’s how my family ended up in Hartsville, S.C., with no property, no land. No crops.

That’s how long ago slavery was.

Sometimes, whenever I had to do official business, I would imagine where the spot is where my great-great grandfather was lynched on the steps of the county courthouse. I always imagine that Earvin Sr. made it to the grassy area in front of the courthouse. There is no reason for me to think this; I just made up the spot because that location is marked with a phrase that reminds me of my history:

They never fail who Die in a great cause. While the tree of freedom’s wither’d trunk puts forth a leaf, even for thy tomb a garland let it be. Conquered they can never be Whose spirits and Whose souls are free.

I first saw that plaque at the Darlington Sweet Potato Festival.

It doesn’t take place on a plantation. There are no slave quarters there. It is the place where my family’s history is stolen. It is just a grassy area in front of a courthouse.

Actually, the patch of grass has an official name:

Darlington County Confederate Park.

I am 35.

I am happy.

My niece gives birth to a son. He will continue this family’s legacy.

His name is Earvin.

America jeers at him.