If you aren’t watching ESPN’s docu-series The Last Dance you’re living life wrong. But luckily for you, I am. So here’s a recap of what the rest of us got to enjoy during Episodes 5 and 6.

You’re welcome in advance.

Is That a Kobe Sighting?

Why, yes. Yes, it was.

Before common sense prevailed, there were plenty of players labeled “the next Michael Jordan”—Harold Miner, anyone?—but only one came close enough to arguably surpass him: Mr. Kobe Bean Bryant.

The two clashed on the court during the 1998 NBA All-Star Game, with Kobe making his first All-Star Game appearance and Jordan presumably making his last, and Jordan felt some kind of way about the 19-year-old who would soon take the league by storm.

“That little Laker boy’s gonna take everybody one-on-one,” Jordan told his peers in the Eastern Conference locker room. “He don’t let the game come to him. He just goes out there and takes it. He just goes out there and takes it. ‘I’m gonna make this shit happen. I’m going to make this a one-on-one game.’”

Jordan added, “If I was his teammate, I wouldn’t pass him the fucking ball. You want this ball again, brother, you better rebound.”

The irony of this moment isn’t lost on anyone, and after telling his teammates he was going to put Kobe to work, Jordan proceeded to bust his ass and put up 23 points, eight dimes, and three steals. He was also named the NBA All-Star Game’s MVP, though Kobe put up 18 points of his own.

“What you get from me is from him,” Kobe said. “I don’t get five championships without him guiding me so much.”

As the Laker legend evolved into an all-time great, they would eventually develop a brotherly bond that would last until Kobe’s death earlier this year.

The Nike Effect

As Jordan’s career began to skyrocket, he locked up lucrative endorsement deals with companies like Wilson Sporting Goods and McDonald’s. But it was his deal with Nike, who he initially had zero interest in whatsoever, that would make him one of the hottest commodities on the planet and revolutionize the entire sneaker industry.

“My game was my biggest endorsement. What I did on the basketball court, my dedication to the game, lead to all this other stuff,” Jordan recalled, while doing the backstroke in billions of dollars. “My game did all the talking.”

Jordan has since become synonymous with Nike, but because black mothers know all, it was his mom who steered him away from blindly signing with Adidas despite Jordan’s affinity for the brand.

“She made me get on that plane and listen,” Jordan said.

“Adidas was really dysfunctional by that time,” David Faul, Jordan’s agent, said. “And they had just told me, ‘Look, we’d love to have Jordan, we just can’t make a shoe work at this point in time.’ I wanted Michael to go with Nike because they were the big upstart.”

After Faulk secured a $250,000 deal with the sneaker giant during Jordan’s rookie season, he set realistic expectations for his client: $3 million worth of sales by the fourth year of the deal. Sneakerheads, however, had other plans, and Jordan ended up selling a mind-boggling $120 million worth of Air Jordans in the first year of his deal alone.

“Before Michael Jordan, sneakers were just for playing basketball,” journalist Roy S. Johnson said. “All of a sudden, sneakers became fashion and culture.”

Jordan’s allegiance to the brand was unwavering too; he refused to display the Reebok logo on his tracksuit—he covered it with the American flag—while accepting his 1992 Olympic gold medal as a member of the Dream Team.

Enter Toni Kukoc

Chicago Bulls general manager Jerry Krause had a love affair with his 1990 second-round draft pick, Toni Kukoc, and would tell anyone who would listen that the Croatian basketball sensation was the future of the Bulls franchise. Slight problem: the Bulls already had superstars like Pippen and Jordan in tow, so this infatuation with Kukoc only created friction between Krause and the proven championship team he already had.

“Krause was willing to put someone over his actual kids who had given him everything we could give him,” Jordan said.

So when it was time for the Dream Team to play Croatia, Jordan did was what Jordan does: he told the entire team that he and Pippen would defend Kukoc. This, of course, led to the young Croatian playing like complete dog shit as two future NBA Hall of Famers mauled him on the defensive end. Kukoc would finish with wounded pride and a measly 4 points in an ugly 33-point blowout.

To add insult to injury, Pippen even implied after the game that Kukoc didn’t belong in the NBA.

“It wasn’t anything personal against Toni, but we were gonna do everything that we could do to make Jerry look bad,” Jordan admitted.

Though try as they may to embarrass Krause, and by extension Kukoc, their future Chicago Bulls teammate played much better in the gold medal game against the Dream Team, putting up 16 points and nine assists in another 30-plus point loss—earning Jordan’s respect in the process.

“After the Olympics, Michael was the most recognizable, the most popular sports figure—but really cultural figure—in the world,” former NBA Inside Stuff co-host Willow Boy said. “He was really a global superstar.”

All That Glitters Ain’t Gold

By ‘92, Jordan was worth an insane amount of money. One of the biggest reasons he was such an invaluable asset to both the league and his endorsement partners was because he averted anything that could potentially jeopardize his bag or tarnish his pristine reputation. This decision, however, came at a steep cost, as his refusal to leverage his power and prestige into supporting noteworthy causes had black folks looking at him sideways.

One of the most notorious examples of this was when Jordan declined to publicly endorse Harvey Gantt, a black Democrat running for Senate in 1990 in his native North Carolina. But it wasn’t just his refusal to publicly co-sign Gantt that rubbed black folks the wrong way, it was the fact that Gantt was running against a notorious racist-ass-racist named Jesse Helms (who ended up winning) and a particular quote attributed to Jordan that confirmed where his own allegiances lay: “Republicans buy sneakers, too.”

“The statement that emerges, ‘Republicans buy Nikes, too,’ sounds as though Michael is saying, ‘My personal wealth is more important than my politics as it pertains to the issue of race,” noted author and educator Dr. Todd Boyd said.

With hindsight now at his disposal, Jordan swears he said that in jest—feel free to roll your eyes, because I sure as hell did—and explains what makes him different from someone like Muhammad Ali, who stood strong no matter how badly White America tried to destroy him.

“I do commend Muhammad Ali for standing up for what he believed in, but I never thought of myself as an activist,” Jordan said. “I thought of myself as a basketball player.”

Or a coward.

In this instance, the two are completely interchangeable considering Jordan has seemingly made it his mission in life to avoid addressing social issues.

But I guess when Republicans buy Nikes, you aren’t left with any other choice, huh?

Unfortunately for Mike, the Harvey Gantt situation wasn’t the only thing chipping away at his mystique. In January of 1992, sports journalist Sam Smith dropped his best-selling book, The Jordan Rules, that included some unflattering anonymous quotes—allegedly from Bulls forward Horace Grant—that didn’t exactly paint Jordan in the greatest light. His penchant for gambling also became front-page news after he dipped out to Atlantic City in the middle of the 1993 playoffs. The media became infatuated with Jordan’s gambling and he grew from annoyed, to defiant, to eventually irate.

“No, because I can stop gambling,” Jordan told Connie Chung when asked if he had a gambling problem. “I have a competition problem. A competitive problem.”

Things got infinitely worse when Jordan was forced to testify in court and explain a $57,000 check that he wrote out to a seedy character named Slim Bouler. Additionally, one of his golfing buddies, Richard Esquinas, also alleged that Jordan owed him over a million dollars for bets they made on the fairway.

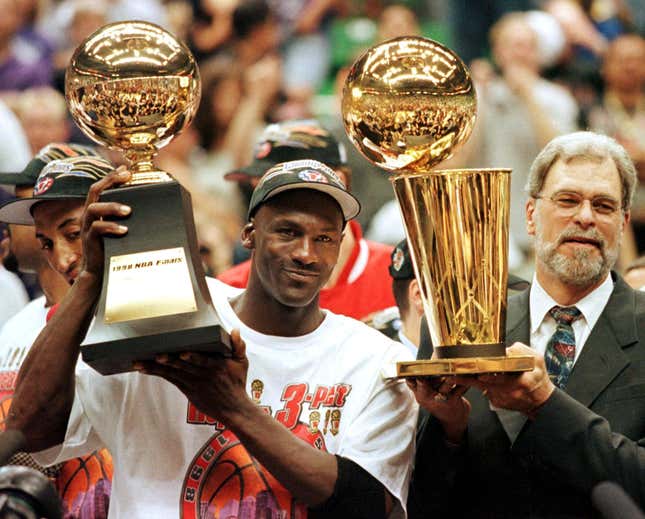

Infuriated by his character being attacked, Jordan refused to talk to the media and instead took out his frustrations on the poor New York Knicks, leading the Bulls to an eventual three-peat after coming back from an 0-2 series deficit in the 1993 Eastern Conference Finals against the Knicks.