White people love critical race theories.

While they generally oppose Critical Race Theory, the academic movement started by Black scholars, they have historically embraced the uncapitalized version of race theory. However, because so many see whiteness as a default, they don’t understand that their entire education has already been racialized. The fact that most people know about Betsy Ross’ amazing ability to sew or Paul Revere’s talent for riding and yelling, but have never heard of Mary Ellen Pleasant or Colonel Tye is proof that the American education system is filtered through the lens of whiteness.

So when Mitch McConnell and 38 Republican senators sent a letter to the secretary of education decrying the ghastly prospect of white students having to learn actual facts about slavery, it was not unexpected. For centuries, this country’s schools have perpetuated a whitewashed version of history that either erases or reduces the story of Black America down to a B-plot in the American script. It’s why they hate Critical Race Theory, The 1619 Project and anything factual—because the white-centric interpretation of our national past is so commonly accepted, white people have convinced themselves that anything that varies from the Caucasian interpretation must be a lie.

This is not new,” Jelani Cobb told The Root. “One of the most under-discussed topics in education is the role slavery plays in the early history of the country.”

Cobb, a journalist and educator, earned a Ph.D. in American history under the supervision of David L. Lewis, who won the Pulitzer Prize for his two-volume Biography of W. E. B. Dubois, the American giant whose early works provided the template for the study of the history of Black people in America. As a professor at institutions from Columbia University to the historically Black Spelman College, Cobb notes that the “propaganda of history” has been so whitewashed that most people don’t realize that they learned a whitewashed version of America’s founding.

“It is important to realize that all history is revisionist history,” Cobb explained. “The established historiographies are constantly revised as we learn more information.”

Even though no teacher in America has been hogtied and forced to teach the curriculum devised by historians, journalists and people who know things, The Root was curious. If The 1619 Project is an attempt to rewrite history, which version of history does the GOP fear is being altered?

The Root decided to see what some of the signatories to Mitch McConnell’s Strawberry Letter knew about slavery and Black history. We dug through state curriculum standards, yearbooks and spoke with teachers to see which interpretation of history the white tears-spewing politicians learned when they were in elementary and high school. In doing so, there are certain things we realized:

- There is no one Social Studies curriculum: Most states’ departments of educations create a K-12 social studies curriculum that sets a minimum standard for what students should learn by a certain grade (Here is Georgia’s). The rest is usually left up to the districts, schools and even the teachers.

- There are two histories: As someone who was homeschooled, this was a revelation to me. The majority of K-12 students cycle through two levels of social studies. The basics of geography, civics and history are usually taught in elementary and middle school. Students learn another, more detailed history and civics curriculum in high school that usually includes separate courses for civics/government, world history, and American history.

- But really, there are three histories: Many states mandate a “state history” course, usually from a limited selection of one or two state-approved textbooks. In some cases, the state course totally contradicts what the students learn in American history classes.

- Sometimes there are four histories. There are some states where students take two different state history courses—one elementary level class and one high school level class.

- ...Or six histories: Take Georgia, for instance. In elementary school, students learn the basics of American history and state history. In middle school, they take world history and another year of state history. In high school, they do it over again, with mandatory courses in world history and U.S. history. However, in Georgia, and in most states, students use textbooks from different publishers and authors, many of which tell completely contradictory versions of the same stories.

- But no Black history: Aside from cursory mentions of the Civil War, Martin Luther King Jr. and the civil rights movement, most state educational curriculums don’t specify how much history should be dedicated to Black history. In Georgia, students have courses on Native American history, Latin American and Caribbean culture, a course that combines African and Asian geography, but nothing specifically on Black history.

Knowing this, we dug through bios, school archives and academic resources to find out how these GOP legislators gained their knowledge of America’s past. In most cases, we were able to find the exact textbook each legislator’s school district used for one of the state or American history courses. In other cases, we were able to find contemporaneous descriptions of the textbooks from academic journals or reports. To our surprise, most received a well-rounded education on the history of Black people in America.

Just kidding. They all learned variations of the same white lies. And, apparently, they’d like to keep it that way.

Here’s what we found.

Marsha Blackburn (R-Tenn.)

What she said: “The 1619 Project is nothing more than left-wing propaganda. Tennesseans don’t want it in our schools. We want our children to learn about our nation’s history.”

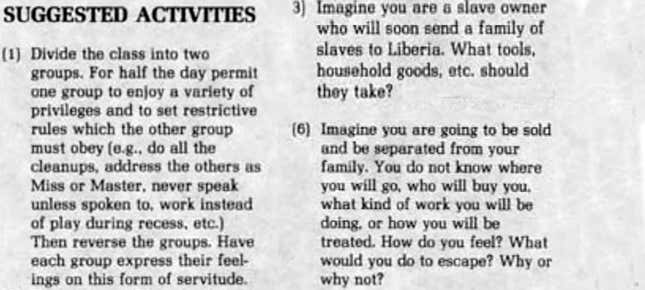

What she read: Although she represents Tennessee, Marsha Blackburn attended elementary and high school in Laurel, Miss. In 1959, the year Sen. Marsha Blackburn would have entered kindergarten in Mississippi, the state legislature handed control of choosing textbooks to Gov. Ross Barnett. At the request of the Mississippi State Society of the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC), the state had already mandated a ninth-grade course in Mississippi history, which means Blackburn learned the history of her state from John K. Bettersworth’s textbook Mississippi: a History.

The New York Times wrote in 1975 that Bettersworth’s catalogs “treat blacks of old as complacent darkies or as a problem to whites.” When The Root reviewed the text, we noticed that the entire history of the 250-year institution of slavery was reduced to five pages. Bettersworth’s book was based on UDC propaganda that taught children that the slave master treated his slaves “as his own,” but noted that most of the human chattel were so lazy that “it took two to help; one to do nothing.” However, Bettersworth was sure to point out the kindness of the masters who educated the enslaved “as they taught their own children.”

Mississippi: A History also treats the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education case as a travesty, insisting that Mississippians were largely satisfied with segregated schools. “Incidents had been extremely rare,” it explained. “[F]or by and large, each race—its parents, its pupils and their teachers, had found it advantageous to remain in an ‘equal but separate’ status.”

The United Daughters of the Confederacy play an outsized role in the way we learn history. Formed in the late 19th century, the group is not only responsible for most of the Confederate monuments in America but perhaps their biggest memorial to the white supremacist utopia known as the Confederacy is how they instilled their beliefs in schools across America. By turning Southern housewives into lobbyists for the Lost Cause ideology, they transformed history into a fictional version of the past, complete with happy slaves and brave, honorable white men who just wanted low taxes. By the early 1920s, they had become so powerful that a history book didn’t stand a chance of being approved if it contained a negative portrayal of the Antebellum South or the Civil War.

Blackburn’s alma mater, Northeast Jones, integrated in the fall of 1970, the year after Blackburn graduated.

Tom Cotton (R-Ark.)

What he said: “The 1619 Project is left-wing propaganda. It’s revisionist history at its worst.”

What he read: Tom Cotton, a 1995 graduate of Dardanelle High School, likely learned his American History from The American Pageant. While Cengage is a relative newcomer in the textbook industry, its high school history book, The American Pageant was used across the country for many years. The text is nuanced and thorough, even in how it presents slavery...most of the time.

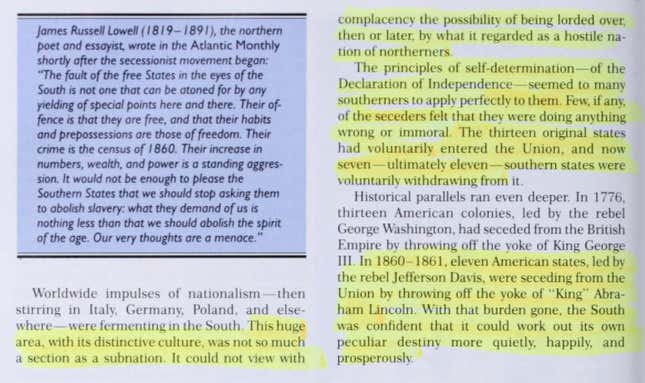

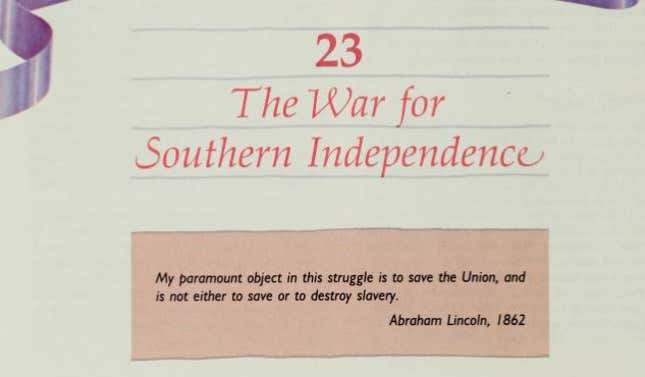

One of the realities of the textbook industry is, because of the UDC’s influence over school districts and boards of education in the South, publishers must choose between telling the truth or bowing out of the textbook market in one-quarter of the country. Cotton’s text never explicitly says the Civil War was about slavery or even refers to it as a “Civil War.” Instead, it carefully couches the “War for Southern Independence” as a clash that had to do with tariffs, Northern overreach, blah, blah, blah. The book also doesn’t quote any of the actual declarations of secession, only noting that the “rebel” Jefferson Davis told the despotic “King” Abraham Lincoln: “All we ask is to be let alone.”

And, of course, the textbook describes the period after the Civil War:

Unbending loyalty to “ole Massa” prompted many slaves to help their owners resist the Union Armies. Blacks blocked the door of the “big house” with their bodies or stashed the plantation silverware under mattresses in their own humble huts, where it would be safe from the plundering “bluebellies”...Newly emancipated slaves sometimes eagerly accepted the invitation of Union troops to join in the pillaging of their master’s possessions.

This would be a theme throughout many of the textbooks. The few passages that described the lives of Black people were usually crafted from single-sourced narratives of enslavers or other white people. “The-thing-that-happened-that-one-time” becomes the mold for “this is how the slaves were,” which is the literal definition of stereotyping.

Perhaps the only thing more racist than this textbook is the name “Tom Cotton,” which sounds like the person you have to fight when you defeat all the other slave masters.

Ted Cruz (R-Texas)

What he said: “Why should the false revisionist history not be used as the basis of K-12 education across the nation? Not because of ‘cancel culture,’ which you support. But because it wrong & deliberately deceptive.”

What he read: Because Ted Cruz attended private Christian academies for his entire educational career, we could not verify the specific book used by Cruz’s elementary school to teach Texas history. However, his Advanced Placement U.S. History class—required in Second Baptist High School’s curriculum—likely used the eighth edition of The American Pageant, which contained most of the same passages outlined earlier. As late as 2016, the text still contained racist themes, according to CBS.

If Second Baptist High School adhered to the standards of the Texas Department of Education, we can surmise that Cruz had to learn speeches from Jefferson Davis, but not that slavery caused the Civil War, which wasn’t taught in Texas schools until 2018. Texas’ social studies curriculum “deemphasized slavery, questioned New Deal entitlements and mandated study of the “optimism’ of ‘thankful’ immigrants,” before 2010, according to the Texas Tribune. The state also believed Harriet Tubman was too sensitive a subject for third-graders but taught that slavery was the “third-most-influential cause of the war.”

Before graduating in 1988, Cruz was a member of the ultra-libertarian Constitutional Corroborators, the high school junior varsity team for the Free Enterprise Institute, which still promotes the belief that the Civil War was mostly about tariffs and economics. We also know that Cruz’s alma mater was affiliated with the pro-Confederate Southern Baptist Convention, which finally reckoned with its racist past in 2018. The institution seceded from the larger organization in 1845 over slavery.

Ed Young, the pastor of Second Baptist Church and former president of the Southern Baptist Convention, recently described the Democratic Party as “godless.”

Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.)

What he said: “I think America is a unique experiment that stood the test of time. We’re better today than we were 10 years ago and, hopefully, 10 years from now, we’ll be better. Striving to be better is always the goal. But, no, I do not believe my state, I do not believe my nation, is systematically racist.”

What he read: Although Brown v. Board of Education officially outlawed segregation in 1955, Lindsey Graham’s school district in Pickens County, S.C., didn’t desegregate until 1970. So it’s understandable why he learned history from The History of South Carolina, published from 1840 until 1970 by three generations of descendants of pro-Confederate William Simms. While Simms’ early versions opined about the “irresponsible, uneducated, unmoral and, in many cases brutish Africans,” Graham likely used the 1958 edition where Mary C. Simms Oliphant, Simm’s granddaughter, had a much more progressive view.

“Most masters treated their slaves kindly,” wrote Oliphant. “Africans were brought from a worse life to a better one. As slaves, they were trained in the ways of civilization. Above all, the landowners argued, the slaves were given the opportunity to become Christians in a Christian land, instead of remaining heathen in a savage country.”

The textbook also notes that South Carolina’s enslaved seldom revolted, which Oliphant says “speaks well for both whites and Negroes.” Apparently, she had no clue that South Carolinians were scared shitless of slave revolts since the Stono Rebellion, the 1739 revolt that influenced America’s “slave codes” more than any other event in colonial history. Yet, of the Civil War, (which she calls the “Confederate War”), the Post and Courier dissected Simm’s interpretation: “The relationship between the whites and Negroes on the plantations was at this time very friendly...For more than four years the women and children had remained on the land with only the Negroes to protect them.”

During Reconstruction, Oliphant praised the Klan for keeping justice alive. “The sight of the mounted klansmen in their white robes was enough to terrorize the Negroes,” she explained. “When the courts did not punish Negroes who were supposed to have committed crimes, the Klan punished them.” While South Carolina was a majority-Black state until 1940, the only Black person identified by name in the 1958 edition is Denmark Vesey, who was executed for organizing a slave revolt.

To be fair, Oliphant learned history from a very unreliable source–her grandfather’s history books.

John Kennedy (R-La.)

What he said: “[Biden] has gone fuel ‘wokerista.’ He has joined those people who believe America was wicked in its origins.”

What he read: John Kennedy attended segregated schools in Louisiana for his entire elementary and high school career. Kennedy’s Zachary High School integrated in 1970, the year after Kennedy graduated. The East Baton Rouge Parish’s desegregation case was the longest desegregation case in American history, finally ending in 2007.

In Heather Stone’s dissertation Never Forget Where You Came From: An Oral History of the Integration of a Rural Community, the scholar details how Black students at Northwestern High School used the tattered books passed down from Zachary High School. We tracked down a copy of the 1952 edition of Louisiana: A History, used by 1968 Northwestern graduate Ella Mae Bowery during her junior or senior year of high school.

Here are some highlights:

- On slavery: Louisiana’s slaves were “among the happiest and most content.” There were very few insurrections because being enslaved in the bordering states of Arkansas, Mississippi and Texas was “a wholly undesirable prospect.”

- On the War of 1812: “The negro population, free and enslaved, joined whites to help defeat invading [British] army.”

- On Reconstruction massacres: “Because of frequent clashes between freedmen and whites, the War Department dispatched Union soldiers to Louisiana while groups of former Confederates like the White League formed to protect whites.”

- On Louisiana’s Grandfather Clause: “The literacy requirement prevented many ex-slaves from voting...Others saw it as an incentive for education.”

- On dentures:

Mitch McConnell (R- Ky.)

What he said: “This is a time to strengthen the teaching of civics and American history in our schools. Instead, your Proposed Priorities double down on divisive, radical, and historically dubious buzzwords and propaganda.”

What he read: From age 8, until he was 12 years old, McConnell attended schools in Augusta, Ga., which means he was required to take a class on Georgia history in the third or fourth grade, using the textbook Our Georgia, which Melton McLaurin describes this way:

The authors of Our Georgia find a solution to the first problem of racial, imagery confronted by any writer dealing with Southern history, the institution of slavery. Since slavery in Anglo-Saxon societies was based on race, and since ante-bellum Southern society was based on slavery, their solution is rather unique—they ignore the issue as much as possible. Eli Whitney sees Negroes picking seed out of cotton, while singing, of course.

Joel Chandler Harris writes stories of slaves, who are also musically inclined. Frank Lebby Stanton writes poems in Negro dialect. That is the extent of the text’s treatment of slavery; indeed, that is all the text says about the Negro. The word “slave” is used in the book five times, the word “Negro” only five. There is however, an entire chapter on the Indians of Georgia, and numerous references to them elsewhere in the book.

The role of the Negro since the ante-bellum period is completely ignored. No attention is given to any of the social problems caused by tne growing Negro militancy of the late 1940s and early 1950s, or the problem race presented in education, although education in modern Georgia is discussed. Not one single contribution to the State of Georgia by one single Negro is considered. The color line does not exist

After moving to Louisville, Ky., and attending duPont Manual High School, McConnell would have learned from an education department that provides grants to Kentucky Educational Television for Kentucky’s Story, which still teaches this about slavery in Kentucky:

Because many owners and servants worked side by side or had frequent contact, the bond between them was more patriarchal than was the relationship shared by slaves and masters in other states. While exceptions can be noted, it is generally believed that Kentucky’s slaves experienced a less harsh life than did those living elsewhere...

Many aspects of the slaves’ lives resembled those of white laborers...In addition to these evening and Sunday activities, masters encouraged their chattels to engage in recreational activities, such as dancing and singing, that provided emotional release; happy slaves worked better than did discontented ones.

Religion also played an important role in the slaves’ existence. Churches encouraged masters to treat their people kindly and urged slaves to be good Christians, to serve their earthly masters as they would their heavenly father and to look for rewards in the hereafter for services rendered on earth.

Tommy Tuberville (R-Ala.)

What he said: “A lot of these kids don’t know. They haven’t been taught. They have not been taught the fundamentals of what this country and how this country was built and why we’re here and why we’re so strong. Why is capitalism so good? Why is it so much better than socialism? We’re not teaching that. We’ve gotten away from it.”

What he read: Although Tommy Tuberville represents Alabama, he is an Arkansas native who likely learned his state history from Walter Lee Brown’s Our Arkansas, used to teach fourth-grade Arkansas history from 1958-1968, according to the Democrat-Gazette.

Brown, a champion of the pro-Confederate “Lost Cause” mythology, was one of the few historians to whom the United Daughters of the Confederacy would give approval, as they controlled the state’s textbooks beginning in the early 1900s.

Some of my favorite quotes from the edition are:

- “The Klansmen told the Negroes to be good and to stay away from the polls on election days. Negroes who refused to obey were visited a second time and taken out and whipped. Negroes who had done crimes but who had not been sent to jail were run out of the state, hanged or burned alive as a warning to others.”

- Conservative Democrats lost elections during Reconstruction because “Republicans herded the Negroes to the polls like cattle, giving them a few coins or some whiskey and tobacco to vote Republican.”

- The Klan was formed “to try to scare the Negroes into being good.”

Tim Scott (R-S.C.)

Tim Scott does not live in a racist country.

Now it all makes sense.

This is why they oppose expanding the historiography of our national story. American schools have never taught a version of history that wasn’t racialized. But, apparently, it’s perfectly fine if the racial narrative skews toward whiteness. They can’t be opposed to learning a different historical perspective because they never learned history; they were spoonfed fiction in bite-sized morsels.

To be fair, it’s understandable why they are so adamant about what they believe in.

Imagine you are a white man. Now imagine what it’s like going through 12 years of school, four years of college, graduate school and an entire career that made you one of the most powerful people on the planet. Now imagine a group of Black journalists, led by a Black woman, told you that you don’t know shit.

Turns out, they’ve been learning a critical racist theory this whole time.