On Sunday the 29th, the New York Times published “Nothing Matters Anymore (Except What Actually Does)“—my essay about some of the existential crises the coronavirus has thrust on us, the violence of the whiplash of the past month, and the electric slide.

I first sent Jen Parker, a staff editor at the Times, a draft on Friday the 20th, and it included the following line:

I do know that it’s likely that some people I know will get sick from this (me included).

Saturday the 21st, however—the day after I first submitted the draft—my dad texted me that he just learned that a person we both knew had fallen ill from COVID-19. So when I received the draft back from Jen last Saturday (the 28th), I made the appropriate edit.

Several days ago, I could say that no one I personally knew had fallen seriously ill from the coronavirus. I can no longer say that.

This person’s name was Stephen Chatman. He died Monday morning.

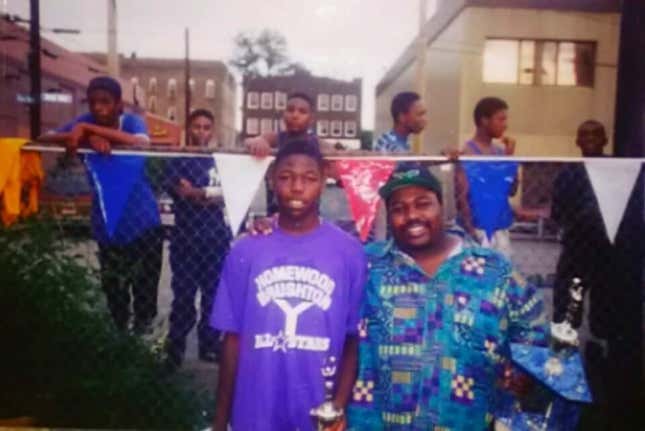

We first met when I was 15, after I signed up to play spring and summer basketball with the Kingsley Association, a community center in East Liberty. My first impression of him, to be honest, was that he was too short, round, and loud to be a basketball coach. He had more of a football look and sensibility. But I immediately grew fond of him—which I imagine was at least partially due to his coaching strategy, which was “Get Damon the ball, and get out of his way.”

He also gave me my first job—a $100 a week gig at the Kingsley, where my job description was basically “teenager who moves chairs sometimes.” It was a sham job that he created for me and a couple of other kids in East Lib. because he knew we needed money. People who remember Pittsburgh’s pre-gentrified East End know that the Kingsley used to sit behind the busway, across the street from where Target currently is. And most days at “work,” we’d just hang outside the building for a couple hours and chop it up.

Steve was best known in the Burgh for DJing, though. He and Don Patterson—Steve’s best friend—hosted a program on 91.3 WYEP called “The Soul Show,” and he also gigged weekends at nightclubs, birthday parties, weddings, and wherever else his talents were in demand.

The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette’s obit had more on his impact:

When Mr. Chatman stepped on the scene at WYEP, he helped bring black music to a station that was “mostly for white folks,” according to Mr. Patterson. Ex-co-host Mr. Canton said he remembers fondly times when Mr. Chatman would give listeners anecdotal history lessons on artists and music they would play.

“We intersected on many many songs of the band Cameo,” said Mr. Canton, the show’s current host who co-hosted with Mr. Chatman for three years around 2006. “He loved Parliament-Funkadelic. And William Bootsy Collins. Steph was loved. But it was a combination of things. One was his depth of knowledge, but the other things was that he connected music with the timeline of his personal life. If you looked at his show descriptions back in the day, he wanted everyone to timeline their life. People still remember now how he helped them.

“He was the last real piece of black radio in Pittsburgh,” Mr. Canton added.

I’ll remember Steve as being boisterous, hilarious and passionate. I’ll remember the white towel he’d rock on his shoulders while pacing the sidelines everywhere from the Homewood Y to the Warrington Rec Center. I’ll remember his laugh, which always sounded like he was the first to get a joke that you’ll eventually get, too. I’ll remember when he took the entire summer league team to Kings Island in Cincinnati, and the iridescent purple uniforms we wore once there. (And I’ll remember the $84 I lost playing blackjack on the van ride down. Don’t remember, though, how I lost $84 when I only took $50 with me.) I’ll remember clubbing in Station Square in my 20s, sometimes seeing Steve behind a DJ booth, and walking back there to pound him up.

But mostly, now I’m just angry as fuck, man. Knowing that so much of what’s happening in America now could’ve been prevented; so many Steves who have died and will continue to die, and that motherfucker is tweeting about ratings.

Of course, the coronavirus would have affected us regardless of how quickly and efficiently the president reacted when first learning about it. Nothing was stopping that train. But what matters is scale. What matters are the months of lying and misdirecting and gaslighting, all because he knew that a hit to the economy would impact his reelection bid. What matters are the hundreds of thousands his vanity will kill.

From what we know about the coronavirus, the last moments of its victims are cruel, painful and terrifying. Your last breaths—if you call them that—are gasps for absent oxygen. You’re also alone, because friends and family are prevented from coming near you. When I think about this, I think about Donald Trump, and my mind goes places I can’t print.

I don’t know what to do with this anger. I can’t let it consume me—and it won’t. Too many people are dependent on me to allow that to happen. It just can’t. I need to keep my family safe. I need to keep myself safe. But right now all I feel is fire. And when I see that motherfucker, all I see is Steve’s blood.