Once, for about an hour, on a hot day in July 2007, I was not black.

This was before people had music on their phones, but I had figured out a way to hook my iPod Shuffle up to my stereo system. After hearing my Uncle Junior play it, I fell in love with James Taylor’s acoustic version of “The Water Is Wide,” and even informed my uncle that I would definitely play it at my wedding (sadly, he passed away before it happened).

When the hillbilly-sounding song came blaring out of the speakers, I knew my friends and family members, who were packed into my living room and den, were subconsciously drafting an official statement for why they would remove my black card. Lucky for me, they were still arguing over an even crazier idea.

Everyone was still arguing when the invited guest, a stringy-haired young white man named Ben pulled up in a beat-up car with no air conditioning. Who was this pale white kid? And why would I even invite them to listen to someone who was dumb enough to drive a car with no air conditioning in Carolina summer heat?

By the time Ben finished his pitch, most of my younger friends had bought in. They even pledged to hold these same kinds of meetings in their own homes. My older friends and family members immediately rejected Ben’s proposal out of hand. They thought his idea wasn’t just crazy, it was dangerous. They thought this pie-in-the-sky plan was whiter than the bluegrass/hillbilly music they heard earlier. They knew that “white people will never let this happen.”

Six months later, they had all bought into Ben’s plan.

On January 26, 2008, nearly four out of five black voters in South Carolina’s Democratic primary cast a ballot for a little-known Chicago senator named Barack Obama.

As a volunteer with Obama’s S.C. campaign, I watched as pundits and political reporters parsed the white vote into infinitesimal slices. The frustrated “soccer moms” voted for Hillary but would later become “Mama Grizzlies” in the general election. The “angry, working-class men” went for Edwards before they became “NASCAR Dads.”

And the people who voted for Obama?

The frustrated black factory workers; the college-educated black youth; the men who barely missed mass incarceration; the economically anxious black middle-class… They were simply discounted as the “black vote.”

Black people are a monolith…

To white people.

I know you’re hearing it.

After Joe Biden’s national press secretary Symone Sanders performed a dramatic reenactment of how Biden dog-walked Bernie Sanders in Super Tuesday’s primaries, the prevailing theme is that black people saved Joe Biden’s flailing presidential campaign. While that simplistic explanation wouldn’t be tolerated for any other political demographic, it more than suffices when media outlets discuss the black vote. Blackness requires no nuance. They don’t even get cool names like “Crown Royal Dads” or “It’s-Some-Spaghetti-In-There Moms”

When black voters finally got a chance to cast votes in South Carolina, the white political punditry posited that S.C.’s black voters were more moderate and less progressive than the rest of the country, an idea that is being parroted across the political landscape by smart white people in well-lit cable network studios.

Meanwhile, Sanders’ white supporters claim that black Southerners are “low-information voters” who lack information. While I was elated to learn that black people have finally become part of the mythical-but-now-dreaded “establishment” after 401 years, a close examination of the actual data reveals a surprising fact:

Everyone is wrong.

There is no “black vote.”

It’s true that black people are the most dependable, consistent voting bloc in America but it’s stupid (and kinda racist) to think that there is a national conference call where negro organizers collectively decide who they will vote for. Or, alternately, white people must assume there is some nationwide melanated mind-meld where black people simultaneously reach the same conclusion. Or, as an astute political observer told me this week, maybe there is one other explanation.

Black people are people.

The youngest demographic of S.C.’s black voters chose Sanders by a small margin while the majority of black voters over 45 chose Biden, according to NBC’s exit polls. But if you look at the turnout number, you can see an explanation that is more plausible than race:

Older black people just voted.

That is your answer. South Carolina’s primaries had record turnout. But young voters, who are more likely to support Sanders, simply didn’t come out to vote. There were three times more black voters over 60 than voters under 30. The same statistic held true for white voters.

It turns out, Sanders’ “diverse coalition of new voters” was not based in fact.

The fact that no one seems to know much about black voters is not the fault of pundits. Sometimes they have no idea because polling data will dissect every aspect of the white vote. You can find the specifics on college-educated, white women voters with advanced degrees who wear fleece vests with yoga pants easier than you can find the data for black voters.

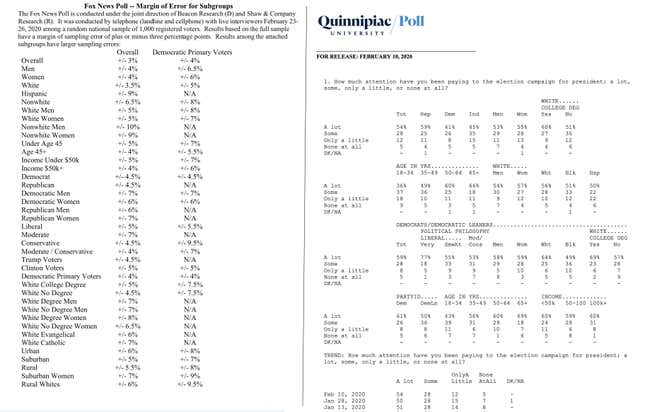

Seriously. Fox News polls break white voters down by sex, education, income, geography (urban/suburban/rural) and religion. But they don’t even mention black voters. They just lump the non-mayonnaisals into one category they call Non-white voters.

Although black women are much more likely to vote than black men, Quinnipiac doesn’t even differentiate between the sexes when it comes to black voters (White voters get separated by education, sex and income). Even America’s two survey standard-bearers, Pew Research and Gallup, don’t dissect black voters past their blackness.

What’s wrong with this?

While you might be expecting the answer to be another version of “black people are not a monolith,” the most troubling aspect is that it dismisses the political needs of large segments of black voters. A black voter in Kershaw County, S.C., has vastly different needs than a second-generation black Brooklynite. A black voter in Alabama is more likely concerned about healthcare and Medicare expansion than someone in Colorado who enjoys universal health care. But instead of discussing and listening to black people, politicians appease the demographic by backing dat azz up or fighting the power. Even when candidates address the subjects we want to hear about, it’s often a facile, performative discussion.

In her upcoming book Say it Louder, Tiffany Cross, founder and editor of The Beat DC, explores the phenomenon of white media outlets’ tendency to streamline every black voice into one aggregated choir singing whichever tune white pundits put in black mouths.

“When white media gatekeepers whitewash the Black American experience, they destroy democracy,” Cross told The Root. “Looking back at the events leading to the 2016 presidential election, the news landscape was consistently unwilling to call out blatant racism that has always led to state-sponsored violence against Black people.”

Cross continues:

We had to die in spectacular ways—cell phone footage of our men getting choked out on the street, bleeding to death on Facebook live, playing with a toy gun in the neighborhood—for our experiences to even be acknowledged. This type of disregard sends a signal to black people that neither our voices nor our votes are a priority. Why? Because reporters and anchors were too busy unpacking white economic anxiety—you know the kind that makes you vote for an incompetent white supremacist as president.

But it’s not just incidents of violence and blatant white supremacy. Because South Carolina’s Republican governor has refused the Medicare expansion, one in five black people in the state is uninsured and 35 percent don’t have adequate health insurance coverage, according to the South Carolina Institute of Medicine and Public Health (.pdf). If those underinsured South Carolinians were white, they’d probably have their own voting bloc. Politicians would talk to “Medically Anxious Moms” and “Pre-Existing Condition Chads” about their health policies. They would lobby Congress and invite politicians to town halls where balding, overall-wearing white men would cough up phlegm between angry outbursts at the government.

But since they’re just “black voters,” they just die...

Spectacularly.

The dismissive aggregation of the “black vote” also leads to white media getting the narrative dead wrong. One of the surprising but underreported facts in politics is that black voters in the South have a higher registration rate and turnout rate than white voters. They register and vote more often than black or white people anywhere else in the country.

Nationwide, the percentage of people registered to vote is 64.2 percent while the turnout rate is 56 percent, according to the Census Bureau (.xls). In Alabama, the black registration rate is 72.2 percent and the black turnout rate is 60.8 percent, five points higher than their white counterparts in each category. In Mississippi, the black registration rate is a whopping 80.9 percent with 68.7 percent turnout. In South Carolina, registration and turnout is 74.8 percent and 64.4 percent, respectively. In each of those states, black people register and vote more than white people.

Which brings us to the takeaway from Super Tuesday. The takeaway from Super Tuesday has nothing to do with a monolithic “black vote.” The notion that one uniform mindset changed the direction of political history is so stupid that it’s unthinkable.

Tuesday was about white people.

Many of those people who voted for Sanders on Tuesday will vote for Donald Trump if Sanders is not the nominee. Some will sit out. Most Sanders supporters will likely vote for the Democratic nominee while most white people will vote for Donald Trump. And the Donald Trump MAGAts will wonder why black people always vote for Democrats. The Bernie stans will wonder why black people voted for Biden.

Among black voters, some will go to the voting booth concerned about healthcare. The older “Macaroni & Cheese Aunties” will simply vote against Donald Trump. Younger black voters, “TikTok Teens” concerned about student debt, will also cast ballots. The “Alternator-fixing Uncles” are also “economically anxious.” The “Day Party Divas” in their 30s have “racial resentment,” too.

Black people have a number of motivating factors that inform their voting choices. We are affected by politics, war and the economy more than any other group in America. The water is wide and we can’t cross over, nor have we wings to fly.

So, instead of perpetuating the idea of international nigga telepathy or a newsletter telling us who to vote for, we should point to the fact that black voters from disparate economic, social and educational backgrounds usually reach the same consensus, and ask ourselves the question I’ve been pondering since my only non-black day some 13 years ago:

What the hell is wrong with being a monolith?

I should’ve asked when I was white.