The premature, unbearable death of Kobe Bryant, his 13-year-old daughter, Gianna, and seven other souls on board his helicopter last Sunday triggered an outpouring of grief rarely seen on this scale. It’s been a week of mourning and tributes: From the Philippines to Philadelphia, makeshift vigils and elaborate murals have bloomed on sidewalks and storefronts to honor the legendary basketball player. This stain of grief—widespread, irrefutable—is the mark of a transcendent personality.

Kobe was transcendent.

But as we grapple with what it means to lose a man of Bryant’s considerable accomplishment and vitality at such a young age—he was just 41 at the time of the crash—it’s also important to note the ways we’ve buried our reckoning in euphemisms. We see it in the numerous obituaries and think-pieces that have cropped up this week. Tucked into the words “complicated” and “Colorado,” is a rape charge that, almost 20 years later, people still struggle to address directly.

The New York Daily News was among the stand-outs this week, with reporter Bradford Davis tracking the lasting effect the 2003 rape case had on how future sexual assault victims would be treated and viewed. Bryant’s defense attorneys in the interest of protecting their superstar client, ran a playbook against the accuser that would be considered indefensible in 2020 by vast swaths of the public.

They used an ongoing mental health condition (for which she was taking medication) to discredit her judgment, and painted a past suicide attempt as a way to “gain the attention” of an ex-boyfriend. They weaponized consensual sex she had with another partner: As the Daily News writes, even though a medical exam concluded that lacerations on her genitals that were “not consistent with consensual sex,” and her blood was found on Bryant’s shirt, the defense team called attention to semen found in her underwear the day of the exam. The alleged victim didn’t wear the underwear on the night she encountered Kobe Bryant, but the mere fact that another man’s DNA was on her clothing was proof, the defense claimed, that multiple partners caused the wounds.

Those tactics would rightly be considered despicable now, but 17 years ago, they were just part of the playbook used to belittle and undermine the experiences of sexual assault survivors. But most important was the material effect the high-profile case against Bryant had on other survivors of sexual assault.

From the New York Daily News:

“In Eagle County, we saw a huge decrease in sex assault reporting,” said [former Colorado district attorney Mark] Hurlbert. “And when victims would talk to advocates, they would say that it was because they were afraid they’re going to be treated like the victim in Kobe Bryant’s [case.]”

According to statistics provided by the Colorado Coalition Against Sexual Assault, the number of forcible rapes reported dropped 10 percent in 2003 from the previous year.

Bryant, in conversation with Jemele Hill in 2014, said he felt he was wrongfully accused. But nearly a decade earlier, a week before his rape case was slated to go to trial, Bryant issued an apology to his alleged victim:

“Although I truly believe this encounter between us was consensual, I recognize now that she did not and does not view this incident the same way I did,” Bryant said in his statement, which was given as part of the condition for her dropping the charges. “After months of reviewing discovery, listening to her attorney, and even her testimony in person, I now understand how she feels that she did not consent to this encounter.”

Rhetorically, “transcendent” functions as the highest honor you give an athlete—or just about any celebrity. People may not follow basketball, but they can recognize Michael Jordan’s silhouette, maybe even quote him or cite one of his better-known career stats (the six championship rings, or the fact that he played through the flu during the 1997 finals). You don’t need to know the extent of Michael Jackson’s discography to know the moonwalk or sparkly glove was his. In a world with fewer and fewer megastars, this kind of transcendence is increasingly rare—even soccer star Cristiano Ronaldo, the most-followed celebrity on Instagram at the moment, pales in comparison to the luster of Jordan and Jackson.

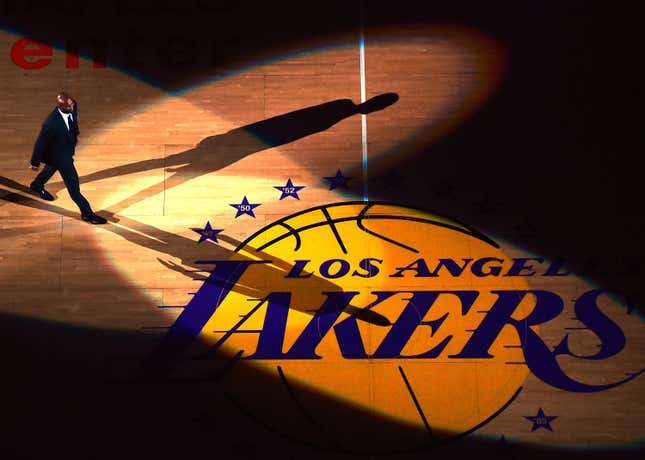

Kobe was bigger than basketball. The millions of people around the world mourning his death make that clear. Channeling “Mamba Mentality”—Kobe’s particular brand of cutthroat competitiveness—speaks to people of all walks of life, as Nike’s campaigns built around the star suggest. But the pedestals we build cast long shadows. Just as Kobe pushed us to reconsider what was possible for one athlete to do—and just as we emulated and mythologized him for those accomplishments—we ensured the damage he wrought would ripple out across time and geography.

Kobe was transcendent. And this is what transcendence means: There are people who only know Bryant for the rape case, and what it taught them about who gets absolved and who gets punished.

I was 17 at the time of his rape case, not much younger than the alleged victim. It would mark a turning point in how I viewed Kobe, but also how I viewed celebrity and its power. I would never look at Bryant the same way again, but he would never engage with the world quite the same way, either. The golden boy of the late ’90s withdrew. In the aftermath of the case and the dropped charges, Bryant lost his endorsements, his stature, his glow. The basketball player who emerged in the wake of the rape charges appeared comparatively sullen, cold, and even more singularly focused. The post-Colorado years would mark the birth of Black Mamba—and by extension, “Mamba mentality.” On the court and in the media, Bryant became a villain—a role he would excel at playing, so much so that it reinvigorated the passion behind him.

“Kobe is a psychopath,” your friends might joke as you watched him completely annihilate a defense, seemingly singlehandedly. Fans of opposing teams relished hating him, even as they shouted “Kobe!” each time they threw a crumpled-up paper across the room into a wastebasket.

It’s impossible to know whether that would have happened anyway—we don’t know what a script without the rape case looks like for Bryant’s career. We do know that the case was formative: that the trajectory of his life, and his career, is cleaved between before that night in Colorado, and after.

Not every superstar athlete gets credibly accused of sexual assault. Kobe was. And at 17, I came to this conclusion: if I went public about sexual assault against a powerful person, it would destroy me.

I had just finished cleaning the apartment with my roommate when he delivered the news of Bryant’s death. I wasn’t prepared for the grief I felt. I hadn’t given Kobe all that much thought in recent years. I didn’t like him. But the fact of his death, how he died and with whom dispelled all of that. I thought of his daughter. I thought of all the parents in that helicopter with their daughters. As I’m sure is true of many others, I thought about their final moments in the air over Calabasas, Calif., and had to fight back tears.

I thought about the Kobe Bryant I was enamored with as a preteen—the Kobe who took Brandy to prom. I knew the contours of his post-NBA life: the devoted family man, the aspiring storyteller. But this past week, I found myself lingering on those images in a way I hadn’t before: Kobe trying to quietly celebrate his Philadelphia Eagles winning a Super Bowl without waking up the baby girl cradled in his arms. His daughter Gigi shooting hoops in heels after a dance; the conspiratorial conversations they shared courtside. Kobe basking in the glow of his pregnant wife, his massive hand palming her swollen belly. There were so many Kobes we lost.

The loss was deepened by knowing the very real pain he had caused. Knowing that there are still survivors who choose not to report their rapes because of his case, because of how victims are annihilated by famous, talented men and the industries and institutions built to protect them. That pain has moved through our communities for decades: the pain of survivors of sexual assault who come to the conclusion that silence is safer than justice.

For some people, every chant of Kobe’s name, every tribute, every gold and purple 8 and 24 will be a reminder of that choice.

That’s the power of the “transcendent” athlete. It’s a power we’re responsible for giving them.

We are not done talking about Kobe, no matter how some of us may wish otherwise. Next month’s NBA All-Star festivities in Chicago will center, largely, around remembrance and tributes to him. Bryant will also be honored at the Academy Awards, where he received an award in 2018 for his animated short film, Dear Basketball. The revelations brought by the ongoing investigation into the crash that killed him, his daughter Gigi, and seven others will also trigger fresh ripples of horror, grief, and anger. Through it all, some of us will try to reconcile all the Kobes we know: The Kobe who advocated for women athletes in a world that still diminishes and undervalues them. The 6’6’’ guard from Lower Merion High School in Philadelphia. The proud dad whose image countered the perpetual pathologizing of black fatherhood. The 25-year-old who said he understood why a 19-year-old woman would believe she was raped by him.

In that space, I hope we acknowledge this was all the same Kobe. I hope we push back against the idea that there is some optimal time to talk about trauma, a line of thinking that serves to bury more than it heals. I hope we don’t absolve our heroes of sins that are not within our purview to forgive. I hope we question the power we give to the people we don’t know but deeply admire. I hope we question the merits and the costs of that admiration.

And I hope, in lieu of another myth, another hero, another transcendent figure, we aspire to something far more valuable—the thing that power and the abuse of it all too frequently rob us of: some humanity.