Given the choice of superpowers, would you rather have the ability to fly or the power of invisibility?

This comic book-based Rorschach test allegedly reveals deep-seated personality traits. Supposedly, people who choose the gift of flight want recognition and praise while those who wish for invisibility are less confident and shun attention. While the question is interesting, psychologists reject it as unscientific because its answer reveals more about a person’s collective life experiences than their subconscious. In many cases, the world has already made the choice.

In America, racism doesn’t always present itself in the bold attire of venomous hate. Most often, white supremacy is cloaked in a suit and tie. It rarely looks you directly in the eye or stares with disdain. It is so vast and wide that it often overlooks your comparatively microscopically small existence. It reduces your desperately loud pleas for acknowledgment to a faint whisper. It makes you feel unseen and unheard.

The reason white school districts receive $23 billion more in funding than nonwhite school districts is that decision-makers don’t consider the historical and economic inequities of redlining and segregation. Courts sentence black men to prison terms that are 20 percent longer than those of white men who commit the same crime because the criminal justice system overlooks inherent bias. This is why it is easy to believe the judges, school boards and employers who contend that they “don’t see race.”

To be black is to be invisible.

New Mayor. Who ‘Dis?

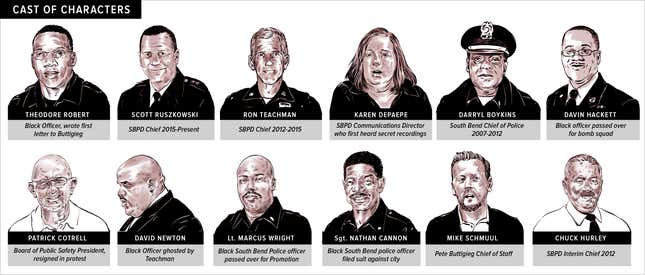

In January 2012, Pete Buttigieg stepped into the South Bend, Ind., mayor’s office after winning the city’s first open mayoral election in 24 years. South Bend had three African Americans in visible high level and public leadership positions: Mayor’s Assistant Lynn Coleman; Fire Chief Howard Buchanon and Police Chief Darryl Boykins.

Within three months, all three would be gone.

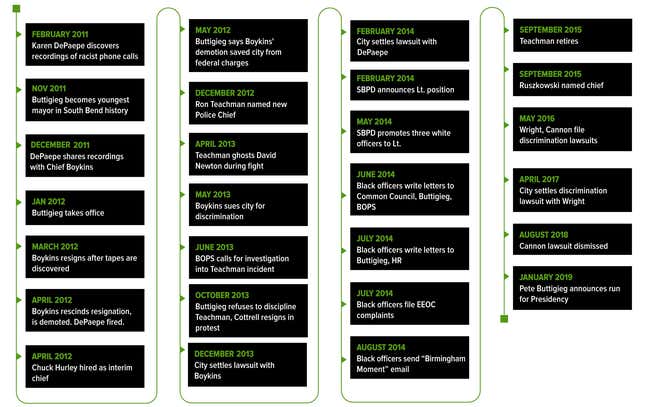

Boykins had served as a police officer in South Bend for 27 years before he was appointed as the city’s first (and to date, only) black police chief in 2007. In 2011, after the city’s police telephone recording system crashed, SBPD Communications Director Karen DePaepe discovered recordings of white officers allegedly using racist rhetoric and concocting a way to get rid of Boykins with the help of top donors to Buttigieg’s then-ongoing mayoral campaign. DePaepe made five cassette tapes of the most egregious remarks and described them in legal documents the city has had for years. One officer allegedly said: “It will be a fun time when all white people are in charge.”

Soon after Buttigieg took office, word got out about the tapes and the officers complained that the recordings violated the Federal Wiretap Act. Even though the recording system had been in place for more than a decade, its existence somehow became the black guy’s fault.

According to Boykins’ eventual racial-discrimination lawsuit, Buttigieg’s chief of staff, Mike Schmuhl, “with Buttigieg’s full and conspiratorial agreement,” told Boykins the feds were investigating him and the only way for Boykins to avoid prosecution was to resign as South Bend police chief.

That was not true.

Two months after Buttigieg demoted Boykins, the U.S. attorney wrote to the city, explaining that before Boykins was demoted, “We advised [the city] that our primary concern was that the SBPD practices comply with federal law.” The phone calls, the top prosecutor wrote, were “mistakenly recorded.”

In testimony that did not become public until this past September, Schmuhl later admitted the feds never directly threatened to indict Boykins. Rather, he testified that “the strong impression the [U.S. Attorney] left with me was that our policies as it relates to telephone recording in the South Bend Police Department were out of compliance with federal law and their guidelines and that there were two people who were responsible for that, and that the impression was to end the investigation, that these policies needed to be adjusted and put in compliance and that personnel actions needed to be taken.”

At the time, according to Boykins’ suit, he believed his three decades of service could possibly end with a conviction on federal wiretapping charges. Boykins would later say in a sworn deposition that he felt “threatened and intimidated” by Buttigieg. After contemplating his decision, Boykins rescinded his resignation and was subsequently demoted by Buttigieg. Buttigieg fired DePaepe for her role in the scandal.

So what happened to the white officers who were heard on the recordings?

- Captain Brian Young went on to lead the county’s Special Victims Unit.

- Dave Wells became the commander of the County’s drug unit.

- Tim Corbett, the county’s homicide commander, ran for Sheriff.

- Steve Richmond retired and moved to Michigan.

Buttigieg claims he has never listened to the tapes because that would be illegal. More recently, in response to a question at an April 2019 CNN Town Hall, Buttigieg not only insisted that he has never listened to the tapes, but he claimed that he doesn’t know what’s on the tapes.

In his book, Shortest Way Home: One Mayor’s Challenge and a Model for America’s Future, Buttigieg wrote:

“Infuriatingly, I had no way of finding out if [the allegations of racist language on the tapes] was actually true. The entire crisis was the result of the fact that the recordings were allegedly made in violation of the law. Under the Federal Wiretap Act, this meant that it could be a felony not just to make the recordings, but to reproduce and disclose them. Like everyone else in the community, I wanted to know what was on these recordings. But it was potentially illegal for me to find out, and it was not clear I could even ask, without fear of legal repercussions. As of this writing, I have not heard the recordings, and I still don’t know if I, and the public, ever will.

Responding to an email from The Root and The Young Turks (TYT) asking if he had ever been informed that there was racist language on the recordings, Buttigieg’s campaign said: “When Pete first learned of the tapes’ existence as a result of the federal investigation, he was not interested in figuring out what the tapes said,” adding that it was “irrelevant to him.”

“[A]ll he knew was what federal investigators had told his office,” explained a spokesperson for Pete for America. “[T]hat the Chief was improperly recording officers’ phone conversations of his employees to determine who was loyal and disloyal to him.”

That was not “all he knew.”

In media interviews following her firing and in her wrongful-termination suit, DePaepe hinted at what was on the secret police tapes. She publicly stated that she’d tried to meet with Buttigieg to tell him what the tapes contained. No one knew for years, but DePaepe detailed the contents of the recordings in a 2012 officer’s report, and in 2013, answered written questions from Buttigieg’s attorneys, both obtained by The Young Turks’ Jonathan Larsen. In his July 2013 deposition, Schmuhl admitted that he “briefly” told Buttigieg that the phone calls contained derogatory and disrespectful comments about Boykins and Buttigieg.

Buttigieg eventually settled Boykins’ discrimination suit against him, Schmuhl, and the city for $50,000. The city paid DePaepe $235,000. The officers who were allegedly captured on the recordings also filed claims alleging that they were recorded without their knowledge. The city settled with the white officers for $500,000 and agreed that they were not “aware of any evidence of illegal activity by the Plaintiffs or any evidence that reveals that the Plaintiffs used any racist word against former Chief of Police, Darryl Boykins.”

Buttigieg repeatedly says he demoted Boykins because Boykins was the “subject” or “target” of an FBI investigation—but the U.S. attorney has never confirmed that Boykins was the “subject” or “target” of their investigation. Pete’s chief of staff confirmed that the U.S. attorney never said it in a deposition.

He also insists that Boykins’ demotion had nothing to do with race and he has yet to comment publicly on the fact that DePaepe’s secret legal documents quote police as saying he agreed to get rid of Boykins before he even became mayor.

No one knows why Buttigieg pressured Boykins to resign and subsequently demoted him. The only thing we know is Buttigieg’s explanation that Boykins was the target of a federal investigation is not true. It was never true. Still, Buttigieg—or proxies from his campaign—continue to repeat it.

This would not be the last time Buttigieg and the city of South Bend would be accused of discriminating against a black police officer.

Over the course of the last month, The Root and The Young Turks have received internal documents, examined formal complaints, and interviewed former officers who outlined a pattern of racial discrimination against black police officers in South Bend. The alleged discrimination spanned the course of multiple police chiefs, captains, and supervisors. The only common denominator is that every black complainant mentions one name:

Pete Buttigieg.

You Can’t Have Institutional Racism Without an Institution

When Buttigieg became mayor in 2012, the SBPD was 11 percent black (29 of 244 officers). There were 28 black officers in 2013; 26 in 2014, and by the time Buttigieg announced his run for president, the South Bend police force was six percent black, with 15 black officers.

Officially, Pete Buttigieg can’t hire black police officers or fire racist cops.

The mayor invoked this legalistic defense during an interview with The Root when he was asked about Aaron Knepper, a white police officer accused of police brutality in at least four incidents since Buttigieg took office. Buttigieg repeated this claim at a contentious June 23 town hall in response to the fatal shooting of a black man by a South Bend police officer.

It’s true that the five-person Board of Public Safety (BOPS) has disciplinary oversight of the SBPD and the fire department—not the mayor. But, as Buttigieg pointed out in his conversation with The Root, the mayor appoints the BOPS members. The mayor appoints the chief of police. The mayor controls the board that controls the chief who controls the police. The ultimate leverage is in the mayor’s hands.

So, why were black police officers leaving the South Bend Police Department en masse?

Racism.

That is not an opinion. It’s what black officers specifically, repeatedly, told the South Bend Common Council, the BOPS and Mayor Pete in memos, emails and complaints obtained by The Root and TYT. The claim is reflected in at least five discrimination lawsuits filed in federal courts. The accusations were leveled in our conversations with current and former SBPD officers. Included in the documents were letters signed by 10 black SBPD officers—a significant cohort of the force’s black members—in which they describe several problems within the department. The letters were sent in 2014 to the BOPS, the mayor’s office and the city’s legislature.

Two other black officers who had not signed the letter filed Equal Employment Opportunity Commission complaints around the same time (both cases were subsequently dismissed)—meaning half of all black SBPD officers were raising their voices and risking retaliation to call attention to the problems.

Since that time, all but five of those dozen have left. And most of the ones who left didn’t leave law enforcement—they just left South Bend law enforcement.

South Bend’s black officers had five basic complaints:

- White officers regularly received promotions, transfers and positions that were not publicly advertised to black officers.

- Black officers were rarely promoted.

- White officers were selected to fill temporary positions. When the department’s black candidates applied for the permanent positions, the white ones would already have an advantage because they had already done the job.

- White officers would not back up black officers when they were in danger or needed help.

- White officers were rarely disciplined while black officers were disciplined very harshly.

Not only is there a mountain of evidence showing that the city’s black officers felt marginalized, but we could not find a single black complainant who said Buttigieg responded to their concerns personally or in writing.

When The Root asked Buttigieg if he was aware black officers had raised issues of racism and discrimination, his campaign would only say that Buttigieg was aware “that some officers had filed complaints with the EEOC, and those were ultimately dismissed.” They also claimed they couldn’t respond because “doing so in the middle of a legal process would’ve been inappropriate.”

To be fair, maybe the black cops were invisible to Mayor Pete.

The Teachman Incident

After Boykins was demoted, Buttigieg replaced him with a white interim chief, Chuck Hurley. Having served as chief before back in the ‘80s, Hurley had ties to some of the officers tied to Boykins’ ouster. After Hurley’s appointment, Theodore Robert, a black officer who would later send some of the letters detailing SBPD’s racism, wrote to Buttigieg, pointing out that Hurley had been embroiled in yet another scandal—having been fired in 2005 from his job as the University of Notre Dame’s assistant director of security for an alleged coverup. Robert also raised questions about whether Boykins’ white replacement was even a certified police officer (pdf). Luckily, according to Pete for America, Hurley had received a “grace period” from the Indiana State Police, to give him time to get certified.

To find a permanent replacement for Boykins, Buttigieg reportedly interviewed 60 candidates in what his campaign calls a “collective community process” before settling on Ron Teachman, a 34-year veteran officer of New Bedford, Mass. Besides a history of clashing with his former city council over transparency issues; having never having stepped foot in South Bend; not working as a police officer when he was hired, and admitting that he could be a little “authoritarian,” the new chief had a lot going for him.

Ron Teachman was white.

On April 22, 2013, four months into his tenure, Teachman was at the Martin Luther King Jr. Center with Lt. David Newton—who is black and would later be a signatory to the letters we obtained—when a fight broke out in the parking lot. Someone said there was a gun. Newton rushed outside.

“[T]here were approximately 50 people in the parking lot engaged in a fight,” Newton told the Common Council (South Bend’s version of a city council). “And I didn’t know if they had weapons or not.”

Newton called for backup but other officers were dispatched on calls. So Newton pulled out his gun and broke up the fight without hurting a single soul. Chief Teachman never came outside to back Newton up. In South Bend’s police department, this isn’t simply a dereliction of duty, it is a violation of the duty manual.

Because they knew how South Bend worked, Newton and his fellow officers didn’t say a word. Newton didn’t file a complaint. But a black pastor who witnessed the event did speak up; he said he spoke to Buttigieg about it. However, according to the witness, Buttigieg “had no answers and did not want to hear what I asked or had to say.” It ended up in front of the Board of Public Safety, which voted to ask the Indiana State Police (ISP) to look into the matter.

Then, according to then-Board of Public Safety President Pat Cottrell and his handwritten journal from that time, Buttigieg fired a city attorney for failing to “deep-six” the ISP investigation into Teachman; a claim Buttigieg denies. When the Indiana State Police handed its results to Buttigieg, the mayor decided not to discipline his new white chief.

Buttigieg refused to release the ISP report, citing personnel matters and claiming the investigation was instigated by people who “want to take a molehill and make it into a mountain,” WSBT reports. Indiana state law only requires cops’ records to be released when they are fired, suspended or disciplined. So, because nothing happened to Teachman, thanks to Pete Buttigieg, we may never see that report.

But South Bend’s black officers had finally had enough.

“I can no longer sit by and watch the flip characterization by Mayor Buttigieg that this incident was ‘a molehill being made a mountain,’” Newton said in a statement asking the Common Council to pressure Buttigieg to release the report. “This statement shows that the mayor has no idea [of] the danger we face daily.”

A few weeks after Teachman was cleared, Theodore Robert wrote to Buttigieg, warning him that an officer had begun an unauthorized investigation into the Teachman incident. Apparently, one of Teachman’s officers was trying to clear Teachman’s name by intimidating officers and tampering with evidence, including confiscating the surveillance tapes from the King Center. Robert (who was suspended by Teachman) and his fellow officers didn’t know just how damaging the ISP report really was. Cottrell, one of the few people who read the report, immediately resigned from the city’s Public Safety Board over Buttigieg’s handling of the case. So what was in the ISP report?

No one but Pete Buttigieg knows.

Until now.

According to an excerpt obtained by TYT, including a summary of its findings, the ISP’s report to Buttigieg found the following:

- Teachman used the excuse that he didn’t back up Newton because he had to pee.

- Not a single witness corroborated Teachman’s account.

- Witnesses alleged that Teachman stood idly by while Newton was outside.

- Confirmation of the unauthorized investigation

- The possibility of evidence tampering or destruction

- Evidence that suggests Teachman tried to get Newton to change his story.

Newton said he wrote to Buttigieg to report retaliation for not playing ball. Newton eventually left the SBPD to become the county prosecutor’s chief investigator. To this day, Buttigieg has never responded to him.

Newton’s fellow black officers would remain invisible.

How to Disappear for 40 Years

Nathan Cannon is a black police officer with the South Bend Police Department. When he retires in March 2020, he will have served on the city’s force for nearly 40 years. Cannon works in the city’s detective bureau and during those years, his superiors rated his performance as satisfactory or better. For more than 20 years, Cannon and other black officers watched while white officers with less seniority or qualifications were promoted to the rank of lieutenant while he continued to hold the rank of sergeant. In February 2014, the SBPD notified all of their officers that there would be an opening for a day-shift lieutenant after the retirement of another officer (a black woman).

No one expected Cannon to get the position—not even Cannon. He didn’t even apply for the promotion to lieutenant of the day shift. The black officers knew that the position belonged to Marcus Wright.

Marcus Wright was black, and he was already a lieutenant. As the department’s afternoon-shift lieutenant, he was already doing the exact same job as the unfilled day-shift position. Plus, everyone knew Wright wanted a transfer to the day shift. Wright was considered a shoo-in, despite what Cannon and Wright would later call SBPD’s “long history of disparate treatment toward black officers in terms of denying promotions to qualified African American officers.” Knowing this, Cannon and the other black officers who had languished in the department without a promotion didn’t even bother to apply. A few white officers submitted applications but everyone thought the job was Wright’s. Cannon’s plan was to apply for the afternoon position that would be left vacant by Wright’s promotion.

Then, what was supposed to be a routine promotion turned into something the black officers had never seen before.

Instead of granting Wright’s transfer, Teachman told him that he would have to interview for the job in front of an interview panel, along with other less senior, white officers. This was the typical procedure for someone who wanted a promotion but Wright was already a lieutenant. He was already a shift supervisor. He wasn’t even asking for a promotion. He essentially just wanted to change what time he came to work. Wright assumed that he would receive a simple lateral transfer that was based on seniority.

Marcus Wright didn’t get the job.

Not only was Wright forced to go through a promotion process that he had previously completed, but Teachman promoted three officers to day-shift lieutenant. Unbeknownst to Cannon, Wright and the other black officers, Teachman had created two additional lieutenant positions, including the head of a newly developed Gang Violence Intervention unit. The chief had filled all three positions by promoting three white officers to jobs the black officers didn’t even know existed.

Cannon, Wright and the senior black officers knew they would probably never see an opportunity like this again in their career. On June 26, 2014, Wright filed a complaint with the South Bend Human Rights Commission. On June 30, Cannon filed his own complaint. After nearly two years, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission issued a letter to both men telling them they had the “right to sue.” So, in 2016, Marcus Wright and Nathan Cannon filed lawsuits against the South Bend Police Department and its chief, alleging discrimination and retaliation.

A judge eventually ruled against Cannon on the grounds that he didn’t apply for the lieutenant positions that he didn’t know existed. Former Chief Boykins also testified that the department usually based the promotion on competitive interviews, not seniority.

In its response to questions about racism in the police department, the Buttigieg campaign pointed to this ruling, conveniently leaving out the fact that the city agreed to an out-of-court settlement with Wright. Pete For America also failed to mention a separate discrimination lawsuit filed by Officer Davin Hackett, another signatory of the letters. His suit is still in court. Officer Joy Phillips, who is white, filed a gender discrimination suit against the SBPD and she prevailed in court.

Discussing the cultural shift in the department’s promotions process, one black officer who would later sign a letter alleging discrimination told us, “Pete Buttigieg, by the demotion of Darryl Boykins, set the department back years.”

In his defense, Pete for America also explained to The Root that Buttigieg only became aware of the concerns of black officers after some of the officers filed EEOC complaints which, the campaign notes, were ultimately dismissed.

Pete Buttigieg is a lying…

Wait.

Maybe Pete Buttigieg can’t see. Perhaps the black officers were not loud enough for Buttigieg to hear. Or maybe he’s deaf. There is ample evidence proving the black cops complained loudly about racism on the force before anyone filed an EEOC complaint. TYT and The Root have examined a slew of court records, memos, and emails, which revealed that the SBPD’s dwindling supply of black cops alerted every available resource to them of the discrimination in Mayor Pete’s police force.

And no one heard them.

Mayor Pete’s “Birmingham Moment”

In June 2014, three weeks before Nathan Cannon and Marcus Wright filed their complaints with the South Bend Human Rights Commission and the EEOC, 10 black South Bend officers (nearly half of the force’s black employees) signed a letter asking the Common Council to investigate “various acts of misconduct committed by Chief Teachman [and] the State and Federal laws broken by Mayor Buttigieg” including racial discrimination; ethics violations; unfair treatment and fostering a hostile work environment.”

The group of black cops also appealed to the Board of Public Safety, outlining a pattern of “discrimination and unfair treatment” by Teachman. They sent a third letter to Deputy Mayor Mark Neal (at the time, Buttigieg was serving in Afghanistan) and the city’s human resources department. Robert had already sent letters to the Indiana State Police, the state Law Enforcement Agency and the U.S. Attorney’s office asking for help.

Combined, the correspondence spelled out numerous accusations, including:

- Teachman creating positions without the approval of the BOPS, so black officers didn’t know about them.

- Buttigieg failing to investigate an accusation by black officers that Teachman interfered with the Indiana State Police investigation.

- Buttigieg knowing that Teachman had nine discrimination complaints against him in New Bedford.

- Teachman not promoting black officers in his old job or in South Bend.

- The failure of white officers, including Teachman, to back up fellow black officers.

- Specific officers who had been overlooked for promotions or lateral transfers.

- Retaliation against black officers who spoke out against discrimination

“It appears that Mayor Buttigieg has given Chief Teachman carte blanche, unrestricted power,” stated one of the June 9 letters, adding: “Chief Teachman has been given the clearance of the mayor to run amuck within the police.”

The 10 men who signed these letters represented almost half of South Bend’s black officers and many of the veteran or high-ranking black South Bend cops. Newer black officers who were not yet eligible for promotions and those who hadn’t been on the force long enough to know the history of the department were not approached. One veteran officer who had been on the force told us he would have also signed but he was not available.

They did not get a response.

One month after the officers sounded the racism alarm to every imaginable agency or individual with the authority to address the problem, they sent another email to South Bend’s deputy mayor asking about the lack of response by the mayor’s office.

Nothing.

In August, the officers sent a scathing series of emails requesting a public meeting with Buttigieg and Teachman. Addressed to directly to Buttigieg, Deputy Mayor Neal and the city’s human resources officer, Janet Cadotte, the emails laid out the same complaints of discrimination and retaliation against black cops. By now, half of the city’s black officers had come together to pressure Buttigieg for a public meeting.

They called it their “Birmingham moment.” (pdf)

“It is obviously apparent that there is a racial divide and along with a smelly atmosphere of inequality that exists here in the City of South Bend and the SBPD,” the letter began. “Since becoming the new chief of police, the white chief has alienated black and white officers throughout the department. The white chief refused to back a black officer when he was in the midst of a potential dangerous situation. An outside investigative agency including our own Board of Public Safety found the white chief to be in violation of this gross act of misconduct but our mayor refused to discipline the white chief. Yet he acted swiftly when he thought the black chief was in violation of the law.”

The letter pointed out that Officer Davin Hackett had been passed over for a promotion to the SBPD bomb squad, despite his military training as an explosives and munitions expert. Newton, the lieutenant left out to dry in the Teachman incident, asked Buttigieg and the HR department for an explanation in a separate email. Over the next five days, the cops would repeatedly ask Cadotte if Buttigieg would meet with the minority officers in a public forum. The exchange grew contentious and Cadotte finally said she would not arrange any public meetings.

Buttigieg said nothing.

“I will never understand how people can fail at their job and move up,” said Hackett, now a corporal with the Elkhart, Ind., police. “They failed. And all of those people are still in power.”

Since signing their names to those complaints letters, nine of the 13 officers who signed those letters or filed EEOC reports have left the South Bend Police Department. The most persistent of the officers, Theodore Robert, later resigned from the force after being demoted and suspended for use of excessive force. Of the four remaining complainants still on the force, exactly zero of those officers has been promoted since they spoke out more than five years ago, including Nathan Cannon.

He is still a sergeant.

On Sept. 30, 2015, Ron Teachman resigned and Buttigieg assigned Scott Ruszkowski, Teachman’s second-in-command, to take over as chief.

Scott Ruszkowsi is white.

“The South Bend Police Department is committed to being a department representative of the diverse community we serve,” said the city’s director of communications, Mark Bode, in a statement to The Root and TYT. “Over the past several years, we have taken steps to standardize the promotion process, published an online transparency hub, invited community input on policies and programs, focused further efforts in relationship-policing, and sought best practices from law enforcement experts.”

Buttigieg, through a spokesperson, still maintains that Teachman “initiated significant changes to the SBPD” and “emphasized a climate of legitimacy, internal compliance, and professionalism,” which included a system for promotions. He also points to his efforts to recruit more diverse officers, most notably his “homegrown project.” Buttigieg also created the city’s first office of diversity and inclusion, which officer Davin Hackett called “a failure.”

The Final Vanishing Act

The difficulty of recruiting and retaining black police officers is not unique to South Bend. Most police departments are whiter than the communities they serve and black officers are the only demographic whose numbers aren’t increasing on America’s police forces, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics. A 2018 Pew Research poll reveals that 53 percent of black cops feel like white officers are treated better, as opposed to 1 percent of white cops who feel this way.

So, maybe this happens everywhere. Maybe the black officers were oversensitive about discrimination. Perhaps they were wrong altogether—which is why Buttigieg didn’t act. It is quite possible a lot of mayors have to deal with conflict and discrimination inside their police departments.

But a lot of mayors aren’t running for president.

During every conversation with a black South Bend police officer, I asked one specific question: “What did Pete Buttigieg tell you about this issue?”

Not a single officer remembered him addressing the issue of racism in his police force.

It is quite possible that Pete Buttigieg didn’t confront this problem because of legal concerns or lack of awareness. That would mean that he never saw the letters from black officers that were addressed to him and stamped by his office. That would mean that he didn’t see the emails. It would mean that he never read the public statements made by Karen DePaepe or her answers to questions from Pete’s own lawyers. That would mean he never read the lawsuit filed by Boykins. That would mean he didn’t know DePaepe asked for a meeting with him. That would mean he didn’t see Nathan Cannon’s lawsuit. It would mean that he had no idea why the city settled a lawsuit with Marcus Wright. That would mean that his chief of staff misremembered telling Buttigieg about cops making “derogatory” statements. It would mean that the city’s dwindling number of black cops was just a coincidence. It would mean that South Bend hired a bunch of black officers who were good enough to work but not good enough to receive promotions.

It could only mean that half of South Bend’s black officers somehow collectively imagined the same kind of discrimination throughout Pete Buttigieg’s entire tenure as mayor. But they were all wrong. And Pete Buttigieg was right.

Ultimately, it does not matter if the black officers were delusional, lying or mistaken. It doesn’t even matter whether or not a judge found the officers were actually discriminated against. If Pete Buttigieg, Chuck Hurley, Ron Teachman or Scott Ruszkowski put imperceptible diversity policies in place and instituted “best practices,” but black officers did not see any changes, then does it matter?

It is undeniably true that South Bend’s black officers felt like South Bend’s institution of law enforcement was racist. The numbers show that South Bend’s tiny percentage of black cops has been cut in half since Buttigieg took office despite his “diversity initiatives.” The records show that black officers complained about it as often and as loudly as they could—sometimes to their detriment. While it strains credulity to believe that Pete Buttigieg didn’t know about these complaints, a worse indictment would be that he knew about it but did nothing to fix it, or even to hear the black officers’ concerns.

But, as you now know, to be black is to be invisible.

Historically, our voices have always been muted. Our pleas have always been ignored. A black scream is easily reduced to a whisper. But for us, the unseen and unheard, there is always a bright side:

At least we get to watch Pete Buttigieg fly.

Editor’s note: This story was written by Michael Harriot and reported in collaboration with Jonathan Larsen, managing editor for The Young Turks.