Did you know that R&B was renamed as “rhythm & blues” from “race music” by Billboard magazine in 1949? The name change reflected upwardly mobile Negroes working diligently to change their social and economic statuses. But, of course, with growth and downright swag comes theft. R&B caught the ears of white audiences, and the rest is a long history of musical theft (ahem, rock ’n’ roll).

R&B has got to be one of the sexiest genres out there. To let high-note hitter Luke James tell it: “R&B is just the musical element, content, tone, the feeling. It’s just a title. R&B is a lot of shit. It’s rhythm and blues. I want the music to wrap around your body and take your mind. Then I want the lyrics to hold you.”

I don’t know about y’all, but that got my attention. R&B requires souful singing with a strong backbeat. It’s our most popular genre, and, of course, black folks created it. It’s said that R&B was developed at the end of World War II and into the 1960s. Artists like Ray Charles, Little Richard and James Brown were some of the most influential artists within R&B.

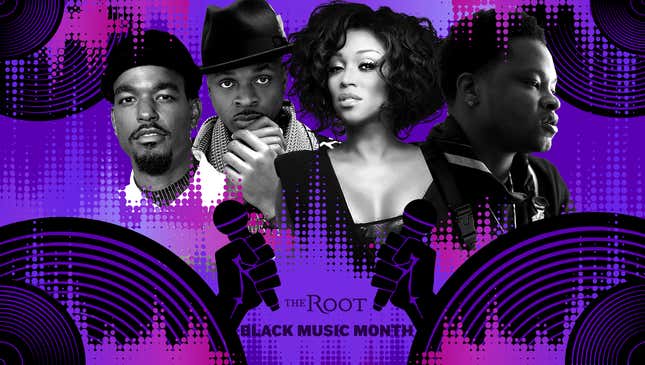

Today R&B can represent so much. From the Isley Brothers to Daniel Caesar, R&B stretches beyond labels. I talked with four different R&B artists: Luke James, Chanté Moore, BJ the Chicago Kid and Stokley (Mint Condition’s front man) about the music industry, racism, the whitewashing of R&B and more.

BJ’s about two songs away from a new album being done. He’s traveled the world and is bubbling with excitement because he needs us to hear his growth.

Chanté Moore’s latest is out, EP 1 of 4, and yes, there will be three more that she’s currently working on with her producer, Ronnie Jackson, while managing to hold on to herself as an artist, but adapt to remain fresh.

Stokley’s finally hitting us with his debut album, Introducing Stokley, that’s all about him and has features you’re gonna want to hear, like those featuring Wale, Robert Glasper and Estelle.

And Luke James? He’s in his happy place, showering the world with the gratitude because life is good. He’s working on music and has a starring role on Fox’s music drama Star. “My life is good!” James laughed.

The Root: What is black music?

BJ the Chicago Kid: It’s soulful. It’s music embodied by our people but speaks to the masses. It’s the news of our lives, the church or our lives, the uplifting and the pain of our lives. We’re amazing at musically expressing ourselves.

Luke James: Black music is emotional. It’s soulful. It’s conversational. It’s transcending, it’s just a profound thing. Black music embodies all music. It’s tribal. It connects differently, it just connects to the core of consciousness. When you listen to the radio, it may not be black folks singing it, but it’s black music. [Laughs.]

Chanté Moore: Any music that a black person makes from the soul is all black. It’s rock ’n’ roll. It’s all black. I mean, Lenny Kravitz is black, but he makes soul music. It doesn’t sound like Jodeci, but it doesn’t have to. There is no designated area for us. We do whatever we do. It’s just us.

Stokley: It’s truth. It’s powerful. It’s attractive. It’s seductive. It’s all these things that people love: black music is black culture. And I think we’ve always been the entertainers of the world. It’s spiritual. Every time I’m on the stage, it’s like a form of prayer and it comes from a real sacred place, and I think it’s become so commercialized that it makes it seem cheap.

TR: Do black artists get the respect they deserve?

S: I remember back in the day, on the billboard you had a “black chart.” Why is there a black chart when pretty much all the pop music is black music? It’s really weird.

But I remember in the beginning stages, it just seemed like we were going into these pop markets and a lot of these people were lesser-known; they get carte blanche for the groups that weren’t very good. But it just comes down to money and politics and that kind of thing.

And here we are, just, you know, rehearsing for hours and have this amazing show and everything; we just got to jump around hoops. And so these things were definitely made aware, and still, to this day, it never really ends, it’s just disguised in different ways. It’s built into the American landscape. You gotta be twice as good, three times as good, which is some b.s., but we gotta continue going forward. The more people try and oppress you is indicative of how much you shine.

CM: The industry itself is divided musically. You have urban, usually just black people; urban can be black and white, but mostly black. But if you’re going to be in pop, if you’re black, you’re not going straight to pop.

TR: Does today’s R&B uphold the integrity of what it was built on?

BJ: Being a business, you must learn the consumer; otherwise you’re definitely bound to drown. I never have to come out of myself. Who you know is who I am.

Believe it or not, Fetty Wap is a singer, Ty Dolla Sign is a singer. These are evolutions of R&B having influences of hip-hop music. Marvin Gaye didn’t have Jay-Z to listen to before he went out and did “Sexual Healing.” We have the evolution of inspiration, and I can’t wait to see what’s birthed from this generation of honest creators, singers and songwriters.

TR: Let’s talk about the whitewashing of soul music.

LJ: To be fair, the world is huge, and everyone has something in them to get out. I fuck with blue-eyed soul. When other artists who are not black sing their soul music, and their soul music is played on the pop radio that’s broadcast throughout the world, they get such a big platform. But when they come with their soul music, we play it on our stations, but they don’t play our music on their stations.

I think it’s more of a thing when myself as a black artist, you’re not able to get the same platform, the same chances, or be put on the same plane. Sometimes, we black artists have to jump through hoops or dumb down our music. It’s the game. I think there’s a lot of room. Things just need to be more fair.

If you look at the ’90s or even in the ’80s, what genre or people, if you will, dominated the awards? Marvin Gaye was performing, Luther Vandross performing, Janet Jackson, Michael Jackson, it was just a wider range, and it was R&B. I just think that the tables have turned. It goes back to the art.

You have to make music ... that people really want to fuck with, and that’s undeniable and breathtaking. It has to be honest. Get to the people. When you get to the people, you got it. It depends on the artist, the art, the vision and the execution. The world is ours; you just got to take the motherfucker. You can’t ask for it.

CM: When a white girl sounds black, it’s easier for her to be on urban music just because she sounds like she fits in, rather than it being that she is a black woman or black man singing.

TR: Why is ownership in music important for black artists?

CM: I think it’s important to continue to expand and try to become better at what I do and be the master of my own destiny. It’s really important, too, if we can to get in the driver’s seat when we can or get people that you trust in a driver seat because someone else can aim your life one direction or another, and it may not be where you want to go.

I think I’ve been in it long enough to know some of the pitfalls and some of the things that are new, and I have a great strong team around me that [is] helping me navigate my way through this. I think empowerment is always a good thing if you use it for your own good. And I just think that that’s where I am right now ... just learning to be a little more proactive rather than reactive in my career.

TR: What is your idea of success?

LJ: I get to create for a living. Shit is gravy. I’m successful as fuck. My mom is taken care of, that’s all. That’s it. I just bought my first property. I’m around my friends who are winning. Here we are living the vision.

BJ: The way you want it to happen will never happen that way. It doesn’t come in the same color box you want, it doesn’t come with the bow on it all the time, but is what you need.

Sometimes, you might like the color blue, but the box is pink. But what you need is still inside. And a lot of times, the covering or the wrapping throws us off and what you need is really inside. Sometimes we’re too picky about the wrong things.

CM: It’s tough to define it. I’ve had a career that has been really long and really wonderful and illustrious. I’ve worked with almost every person that I’ve wanted to work with, but I haven’t reached the height of what I would have wanted to reach yet. It’s not over because I’m still here, I’m still singing, still creating, and I still feel like there is more in me to get to the world.

So it really has to become something that you personally make for yourself. And I don’t know if the bar ever stops, because I don’t know if I had $17-20 million I would go, “Oh yes, that’s it. I’m done.”

It really isn’t about that. It really is about being able to be creative when you want to put music out and people still wanting to come and see you sing. Being content where you are is the most important thing. You have to be grateful, and you have to let go of things that haven’t gone your way; you have to not look back, but appreciate what’s behind you.

TR: Most iconic career moment to date?

CM: Oh gosh, working with Prince and being in the purple limo. He picked me up in it and took me to Paisley Park, and I was able to get a tour of it and ... he just was so fun to be around. I dreamt of this moment for so many years, just like everybody else. I dreamt for this moment for so long. He was like, “What happened?”

I said, “In my dream usually I go, ‘Hi!’ and before I get to touch you or talk to you, you turn into somebody else.” He goes, “That sounds like me.”

S: Prince, of course! Meeting him and hanging out with him. Stevie Wonder is another one. Every time I see him, it’s like the first time all over again. And just hearing different things that people in the industry have said about you. Gladys Knight and Greg James, God rest his soul, have said some complimentary things.