You don’t have to wonder where Nikki Giovanni is on a Saturday night. The iconic poet, who just released her latest collection of poems last week, is a devout Saturday Night Live fan and is especially impressed by Alec Baldwin and his Donald Trump impersonations.

“He has Trump nailed as the fool that he is,” Giovanni tells me. “And I think that that’s wonderful.” We are talking over the phone, but I can tell that she’s smiling. She says, in this first year of Trump’s presidency, that she’s really been enjoying watching comedians.

“Nobody—I am, I hope, a good poet—but not nearly as many people read me as watch Jimmy Kimmel. So watching now, in this day and age, in the 21st century, I think we really have to give credit to the comedians,” Giovanni says, adding, “I think the comedians read the poets, so I think it all works out.”

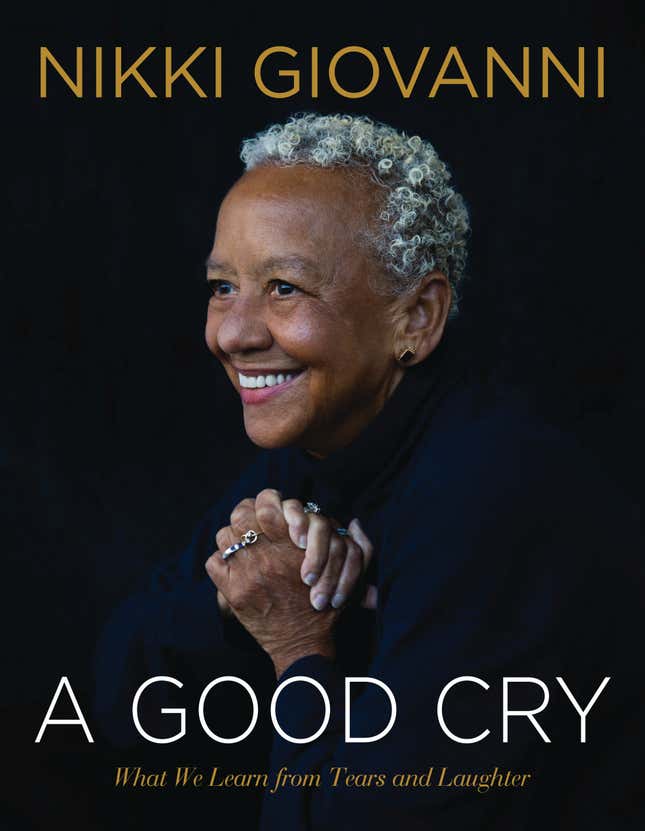

The 74-year-old writer, activist and English professor spends much of her time laughing—her form of self-care since her grandmother used to read the “Laughter Is the Best Medicine” section of Reader’s Digest with her. But Giovanni’s latest collection, A Good Cry, What We Learn From Tears and Laughter, from William Morrow, charts new territory for the poet—delving deeply into memories of loss and abuse. The collection was inspired by the deaths of Giovanni’s mother and older sister.

Giovanni’s mother died 12 years ago on June 10—her sister followed four weeks later. In that time, Giovanni tells me, she was simply too busy to cry.

“If you looked at movies or on television, you’d think women cried all the time,” Giovanni says. “But we don’t, because we always have a lot to do.

“There was a lot going on,” she continues. “There was nobody to handle things but me. So there was no question of, you know, are you going to sit down and cry and go through this. The thing is, you had things to do. You had people to bury, you had things to take care of.”

Giovanni realized that what she went through, a lot of women have gone through. And she believes—much to the consternation of her doctor, she says—that years of holding in and repressing her feelings eventually led to a stroke.

“My doctor and I have been laughing—well, he doesn’t laugh; I do,” Giovanni confides. “Gregory is like, ‘No, no, you had a seizure because you have high blood pressure.’ And I said, ‘No, Gregory, you’re wrong about that.’ And so we been fighting back and forth about why people have seizures. I think people have seizures because they hold things in. I really do.”

All poetry is necessarily intimate, but Giovanni’s coming to grips with the events and losses that have caused her the most pain means that the poet, who has been writing since the ’60s, is getting personal in ways she hasn’t before. Among the most striking poems of the collection are Giovanni’s recollections of the abuse her mother suffered at the hands of her father.

In “Baby West” (named for Giovanni’s godmother), Giovanni writes of the time she spent being raised by her grandparents:

All I knew then

Was the sound

Of my father hitting

My mother every Saturday

Night until I heard

Her say “Gus, please

don’t hit me”

And I knew my choice:

Leave or kill him.

But highlights from Giovanni’s 27th collection of poetry also include short, often autobiographical essays. “Nikki Giovanni: A Look at the Development of This Small Business” chronicles Giovanni’s tremendous work ethic since she was a child. “It seems to me I’ve always been a small business,” Giovanni writes, detailing how she used to wax floors for her grandmother’s friends. “Now my business is poetry.”

Because she covers so much ground, the collection reads like a retrospective. In a recent interview with Salon, Giovanni said that her poems explore what makes us sad: aging, death, abuse, stints in hospitals. But the book is also very much a celebration of a life well lived. One of Giovanni’s strengths over her decadeslong career has been her ability to capture small moments and routines, kneading new meaning into the overlooked details of the everyday.

“What really is a poem:/Buttered corn bread/A pork chop browning/a quilt being pieced/a grandmother’s tears,” Giovanni asks in a poem named after fellow poet Rita Dove.

Many of the poems in A Good Cry are dedicated to people Giovanni has known. Among the most notable poems are several dedicated to her good friend Maya Angelou, who died three years ago. Giovanni spends some time exploring her relationship with Angelou, or “Doc,” as she called the famous memoirist, poet and actress.

“The Maya that I know is going to be different in different places,” Giovanni says, explaining why she decided to include multiple poems dedicated to her friend. “And different people had respect and love for Maya.”

Giovanni writes about Angelou’s love of cooking, how she’d wake up in Angelou’s home “not knowing who would be down to breakfast.” In “Remembering Maya,” Giovanni writes, “I wanted to fry chicken for her but time just ran out.”

Giovanni says, “You want to make sure that people know how you feel, but you’re going to feel a different way each time.”

With A Good Cry, Giovanni explores the life of memories, revisiting the same events in different contexts. But the poet isn’t afraid to envision a bold future, proposing that we push forward into new continents (Antarctica) and new frontiers (space).

In Giovanni’s eyes, black Americans—descendants of those who survived the Middle Passage—are the best equipped to embark on journeys into these new worlds, citing the ancestors’ imagination, faith and perseverance.

Equally important, she wants black children and black women to be at the forefront.

“If we know anybody in space can handle anything, it’s going to be black youngsters,” Giovanni says confidently. “We know what white people do when they go to strange places: They kill. And that’s not even a mean statement.

“I really think we have to send black women, because black women get along with everybody,” she continues. “We embrace everybody. We eat everything.

“Whatever it is that we have, we name it and we love it,” she adds. “Black women are a great people, and so we’ve got to get black women involved.”

While A Good Cry ventures deeper into Giovanni’s life than her previous work, she closes out the collection with a trip to the National Museum of African American History and Culture in the poem “The Museum (at Last).” It’s a poem that lingers on black Americans’ shared past and breathes hope into a collective future.

“We have to look at what black Americans have given to this country. And we have to realize that black Americans are, essentially, the only real Americans.” Giovanni explains. Unlike other Americans, “We were created here.”

She continues: “We learned the language here. We learned and created a cuisine here. We definitely created on the way over here. We definitely created a song, and that song, that hum, that moan, is going to be the basis of the music that becomes American music. So I think that it was important that we, with pride, look at what black Americans have done.”