The phrase “black America” may often be overlooked as a trite colloquialism, but it gives voice to the collective experiences of a community forged in fire.

Black America is not enveloped inside or beneath the United States of America that we love to hate and hate to love. No, black America exists alongside a nation that genuflects to its Founding Fathers as sacred modern-day apostles, conquering gods who made freedom and liberty from scratch with nothing but a stolen land and the blood of people in chains.

Black America is neither African nor European. Created out of a strange combination of necessity, inequality and ingenuity, it has its own distinct identity and origin story. Point Comfort is black America’s Plymouth Rock, and it landed on us a full year before the Pilgrims landed on the Wampanoag Nation. Sullivan Island is black America’s Ellis Island, where shackled human chattel was dragged from Africa into a new world. Martin and Malcolm are this parallel nation’s Jefferson and Adams.

And most people agree that the capital is Atlanta, home to the Atlanta University Center, which is made up of three of the most revered institutions in black America.

In black America, the Ivy League—Harvard, Yale, Princeton, et al.—pales in comparison with the Ebony League. Which HBCUs can stake claim to this rarefied status may be debatable, but there is no dispute that Howard University, Tuskegee University, Hampton University, Dillard University, Clark Atlanta University, Fisk University and Spelman College are all among them.

And then there is Morehouse.

Founded in 1867, two years after the end of the Civil War, Morehouse College is one of black America’s crown jewels. It is one of only four colleges in America that exclusively provide men with a liberal arts education. Located in Atlanta, the men-only college has educated black men for more than 150 years.

If you speak with anyone at Morehouse—students, faculty members, staff, even someone passing by—you are sure to be immediately impressed. Morehouse’s reputation does not merely come from its rigorous academic standards; it is built on a century-and-a-half of sustained superiority. It not only creates scholars, but for more decades than you can count on your fingers, Morehouse has been a factory of black excellence, rolling out men like Spike Lee, Samuel L. Jackson, Julian Bond, Saul Williams, David Satcher, Edwin Moses and Bill Nunn.

Of course, Morehouse has had its share of scandals. In 1989, sophomore Joel A. Harris died during a hazing incident while pledging Alpha Phi Alpha. In 2009, an employee of the school was fired for making homophobic comments (pdf). Less than a year ago, four Morehouse athletes were arrested and charged with rape and sexual assault.

Yet Morehouse has long served as the voice, soul, heart and conscience of not just the dark part of this country, but of America itself. As director of Homeland Security, Jeh Johnson (Class of 1979) kept this nation safe. Lerone Bennett Jr.’s (Class of 1949) book Before the Mayflower: A History of Black America is the definitive history of black America. Martin Luther King Jr. (Class of 1948) unquestionably showed the world that “love is stronger hate” was more than just an overused aphorism. Black America needs Morehouse. America needs Morehouse.

But Morehouse is falling down.

At the center of any institution of higher learning are two separate but important entities: the students and its faculty. A college exists to educate its students, and without the educators, it fails. They are the people in the trenches, on the ground, learning and teaching, leading and being led. They are the heartbeat of every university—black or white. Without them, schools are nothing but collections of buildings, chalkboards and desks.

In January 2017 (pdf), student leaders from Morehouse, frustrated with the leadership at the college, went to court and filed a restraining order against Morehouse’s board of trustees.

On March 22, the faculty of Morehouse held a meeting to address a litany of concerns, rumors and problems facing the institution. The meeting concluded with a simple statement from the faculty (pdf):

The faculty of Morehouse College expresses a vote of no confidence in the current chairman of the board of trustees of Morehouse College.

This lack of confidence did not explode from a single situation. It is the result of an infected, festering boil that eventually turned into a tumor. For years, Morehouse College has been the battlefield for a silent struggle of power that vacillates somewhere between a civil war and a Baptist church deacon board dispute.

It is a yearslong slap fight for the steering wheel of one of black America’s most valuable institutions between a board of trustees strongman, a lone, fearless savior, a gaggle of passionate fire-blooded warriors and a quiet, dedicated group of steel-willed educators. The thing that separates them is also the thing that binds them together. Every single one of them loves Morehouse as much as life itself, and each of them believes the other might ruin the beloved institution.

Over the past few weeks, The Root has spoken with 13 members of Morehouse’s staff, alumni, faculty and students, reviewing several documents—including emails and court documents—accounting for much of the conflict at the institution. What we discovered beneath the polite smiles and aged artifices was an institution teetering on the edge of an outright melee, rife with seething resentment cloaked in academic protocol.

Morehouse College is on the brink of a crisis, and almost no one knows it. Not the students who were so upset with the institution’s hierarchy, they took the college to court; not the faculty members who desperately reached out to The Root because they were so concerned with the situation at the school; not the board of trustees that stiff-armed every other source of input; and not even its president, who—after possibly rescuing it from the brink of insolvency—was unceremoniously shown Morehouse’s front door and instructed to not let the doorknob hit him on the way out.

This war has two fronts: On one side is the faculty of the college. They are the dedicated scholars who understand the day-to-day struggles the school faces. They occupy the offices, hallways, laboratories and classrooms that give Morehouse its stellar reputation.

The only entity more invested in the success of Morehouse is the student body—the soldiers on the ground. No one else spends more time in the hallowed halls of Morehouse; they are the lifeblood of the institution, and it is their money that pays the bills. When anyone speaks of the legacy of Morehouse, they are talking about the former and current students. They are Morehouse.

The college is run by a combination of the president of Morehouse and its 40-member-strong board of trustees. (Most college boards average around 11.8 trustees.) The boundaries and responsibilities for each are spelled out in the school’s bylaws. The board appoints the president, who manages the college. At the top of Morehouse’s board of trustees sits its chairman—Robert C. Davidson.

Davidson graduated from Morehouse 50 years ago, but according to interviews, statements and pages of emails and other documents obtained by The Root, he is accused of running the college like a dictator, unwilling to yield or compromise with any outside voices. Faculty, students, a consulting firm, an accreditation committee and an independent analyst have all warned Davidson that the board of trustees’ actions were hurting Morehouse, to no avail.

In response, the board of trustees stacked its roster with cronies, often using undemocratic tactics to silence the faculty, students and even the school’s president. The faculty and students instead, as primary stakeholders in the institution, demanded their voices be heard, but Davidson and the trustees would not budge.

So they decided to fight.

The Man Who Saved Morehouse

Like each of the college’s presidents since 1967, John Sylvanus Wilson is a son of Morehouse. After graduating from the school in 1979, he went on to Harvard to earn two master’s degrees (in theological studies and education) and a doctorate in education, focusing on administration, policy and planning. Wilson’s résumé includes a stint at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Wilson guided MIT through two record-breaking fundraising campaigns before leaving for George Washington University, where his research focused on “best practices for the sustainability and stability of colleges and universities, as well as transformative advancement and finance in higher education.”

When President Barack Obama decided that his administration should help America’s HBCUs in 2009, he tapped Wilson to lead the White House Initiative on Historically Black Colleges and Universities. Wilson worked inside the Department of Education for four years, guiding the executive branch’s efforts to strengthen black institutions of higher learning.

Then, in 2012, Mother Morehouse came calling.

Two faculty members who contacted The Root on the condition of anonymity both insist that John Wilson’s résumé and experience was just what Morehouse needed to pull the school from the brink of crisis. Independent reviewers agree. In 2012, Morehouse’s enrollment was down 20 percent over a six-year span (pdf). It was hemorrhaging money, and its endowment was down. Perhaps most troublesome of all—it was graduating fewer students. In the face of these indicators, President Robert M. Franklin offered his letter of resignation (pdf) on Jan. 30, 2012, after serving the shortest presidential tenure in the history of the college.

Enter John Sylvanus Wilson.

Wilson’s entire career had led to the moment. He had spent his professional career figuring out how to make colleges and universities financially sustainable. He had conducted peer-reviewed research. He had seen the calamities facing every HBCU in the country. He was built for this.

Aside from the school’s dire situation, Wilson’s only obstacle would be the culture of unyielding power cultivated by the men who had long held the reins at Morehouse. When Wilson slashed redundant faculty and staff, he experienced pushback from some of the “old heads” at the 150-year old institution. When he advocated for drastic budget changes, he angered some longtime faculty and board members. One professor told The Root about a lavish party that trustee members wanted to throw for a beloved member of Morehouse’s collegiate family. Everyone was on board for the event, but when it was presented to Wilson, he squashed the idea—citing the college’s finances and how it overstepped the explicit boundaries granted to him in Morehouse’s bylaws.

The stakeholders at Morehouse were split in their initial opinion of John Wilson. Some thought he was too much of a by-the-book, slash-and-burn president who had no consideration for the traditions and family-oriented spirit of the beloved establishment. Others thought his no-nonsense approach was just what the school needed.

“To be fair, part of it may have been [Wilson’s] disposition,” said one faculty member. “Where [previous presidents] were more of the ‘shake hands, kiss babies’ types, Wilson spent his time raising money and reforming academics.”

But most of the resistance to John Wilson came from Morehouse’s board of trustees—specifically its chairman, Robert C. Davidson.

When two grown men can’t stand each other, one may not ever notice. To reach the top tier of any corporate or academic environment, one must learn to camouflage emotion and hide disdain. Yet, everyone on the campus of Morehouse College knows Bob Davidson can’t stand John Wilson.

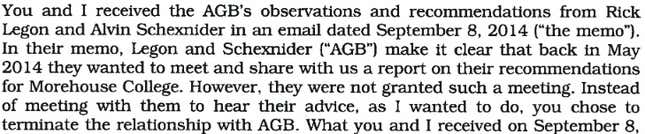

In 2014, Morehouse hired the Association of Governing Boards’ consulting firm to give a critical assessment of the school’s governance. AGB is a nationwide organization specifically dedicated to the governing boards and foundations in higher education. Almost every college in the country seeks its advice and leadership. If any group in the world could figure out what was wrong at Morehouse, AGB could. After looking at the finances, habits and practices of Morehouse’s leadership, AGB issued a document summing up Morehouse’s governance policies (pdf). It reflected two issues:

- The chairman of the board of trustees can’t get along with the president.

- The board of trustees is too large, and composed of too many of the school’s legacy good ol’ boys—or, as AGB’s report called them, “an insider group of board leaders who are seemingly making the key decisions ...”:

Current challenges call for an array of voices. Many alumni trustees display a fondness for what they remember from their days on campus. While not surprising, it might not be what is best for Morehouse College—can only alumni care about the future of the college?

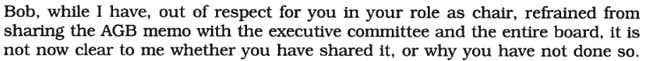

When he learned of AGB’s findings, records and personal correspondences obtained by The Root show that Davidson immediately fired AGB before the consulting firm could tell the entire board of trustees. According to interviews, faculty and students would not learn of the AGB report until nearly three years later. It would appear that Davidson wanted to hide AGB’s findings, while Wilson thought everyone should know.

Four months later, on Sept. 14, 2014, Wilson, frustrated with the lack of changes and compliance with the AGB recommendations, sent a letter to Davidson begging him for an airing of grievances and to restructure the board (read the letter in its entirety here [pdf]) for the benefit of Morehouse, saying in part: “Ultimately, I humbly submit that this is not about you and me. It is not personal. It is about Morehouse College.”

Wilson also indicated in the letter that he was perplexed as to why Davidson chose to hide AGB’s findings:

President Wilson explicitly appealed to the board chairman to reveal the contents of AGB’s findings (pdf), asking, “Does it make sense not to share the AGB letter ... together?”

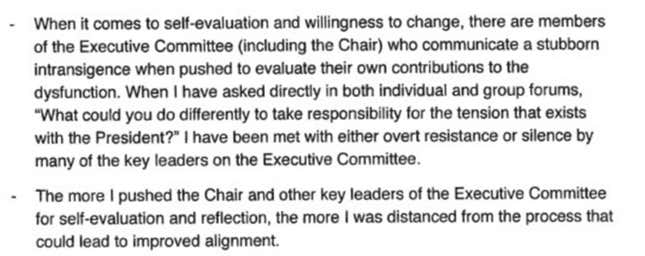

A year later, industrial psychologist Keith Eigel completed an assessment of the board’s governance and concluded that:

... President Wilson is a highly effective, mature, capable and principled leader. ... His rare and unique strengths are a great fit for Morehouse at this time.

and

I believe that the board of trustees itself is the only entity that can take responsibility and ownership of its own contribution to misalignment between this administration and the board.

Then, in April 2016, Belle Wheelan, president of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS, the body that accredits colleges), addressed Morehouse’s board and expressed two concerns: “size and number of Morehouse graduates who serve as trustees.”

After three warnings from objective voices, most people would expect Davidson to change the board’s practices. Maybe the board of trustees would slim itself down. Maybe it would adhere to the bylaws. Maybe it would stop stocking the board with old-head alumni entrenched in a bygone era.

Neither happened.

But, slowly, Morehouse rebounded. In 2016, enrollment increased for the first time in six years (pdf), and it is expected to grow in 2017. The school’s two best years in alumni fundraising were 2015 and 2016. Annual fundraising was up 41 percent. Strive Masiyiwa, Zimbabwe’s richest man, committed to creating a $6.4 million trust to send 40 African students to Morehouse. Newell Brands offered $1 million in STEM research. A world-renowned architect wanted to design a groundbreaking building for the campus. Several faculty members and administrators confirmed to The Root that Apple planned to give millions to the school (estimates ranged from $20 million to $60 million). John Wilson had made Morehouse great again.

In all fairness, John Wilson probably didn’t save Morehouse by himself. The institution survived 150 years without him, and it probably would have weathered this storm. Even with Davidson’s antagonism, there are too many great black men scattered throughout America who revere the sacred space of Morehouse to let it sink forever into the abyss. Wilson may have been sitting in the big chair, but the comeback was probably a combination of the dedicated faculty and staff, the talented students and everyone in the Morehouse universe’s dedication to the school.

In keeping with the ethos of black America, the contentious infighting at Morehouse was family business; and aside from the tangible tension between the board and Wilson, everything was sunny at the ’House. Alumni were giving. Students were applying.

Then, on Jan. 13, 2017, after Morehouse’s Student Government Association president furiously rushed to a courthouse to file a restraining order against its chairman and the entire board of trustees; after the board kicked out the faculty who languished in the trenches on Morehouse’s campus every day serving the students and the academic reputation; after rebounding from an institutional crisis the likes of which had already swallowed an HBCU less than 2 miles away; after a man left the White House to guide his alma mater back to relevancy; for reasons no one who spoke with The Root can figure out, Robert C. Davidson and the Morehouse College board of trustees kicked John Sylvanus Wilson to the curb.

The Soldiers on the Ground

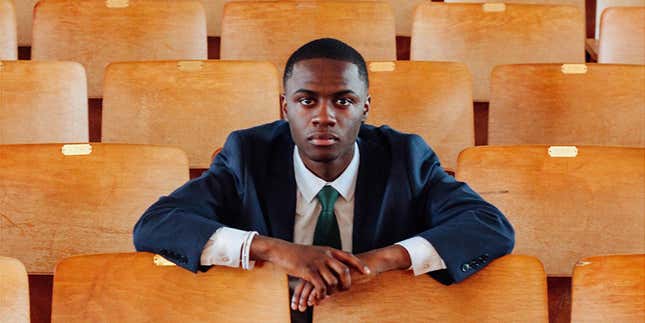

After a few seconds of conversation with Johnathan Hill, you can tell how much he loves Morehouse. It leaks from his pores and spills from his lips. Because of this, it is also easy to see why the men of Morehouse elected him as their student body president. He exudes a fiery passion so contagious that anyone who listens to him speak will believe that he will fight for his alma mater.

As the president of the Student Government Association (pdf), Hill, as well as two other student body officers, is entitled to a seat on the board of trustees. The three are included in most decisions made by the board, and these student trustees were part of the group that decided to hire John Sylvanus Wilson. Hill says he believes the advice of the student body is integral to the college.

“They are the ones who must bear the weight of those decisions,” Hill told The Root. “They are the ones who are on campus every day and are part of the living, breathing history of Morehouse—not the Morehouse of 50 years ago, but the Morehouse of today.”

Hill was at the board of trustees meeting on Oct. 7, expecting the body to vote on extending John Wilson’s contract. Instead, trustees elected four more members to the board—all Morehouse alumni—in blatant disregard of the recommendations of the Association of Governing Boards (pdf), the independent analysis of Keith Eigel (pdf) and the advice of the accrediting body’s president, Belle Wheelan (pdf).

So Hill, his fellow student trustees and the faculty sat in the October board meeting waiting to vote on whether they should extend John Wilson’s contract. Instead, they watched Davidson add four more alumni to the board, unaware of how dangerous this was to the health of Mother Morehouse. Davidson curiously tabled the vote on Wilson’s contract until January, but he issued a statement assuring everyone that John Wilson had the full support of the board of trustees.

Even though the student trustees were now vastly outnumbered by alumni trustees, they weren’t worried—they’d have their say at the next meeting in January. The faculty trustees weren’t worried, either. They’d be in the room at the next meeting, too. They would voice their opinion. What could go wrong?

As it turns out, everything.

On Jan. 9, 2017, four days before the Jan. 13 meeting of Morehouse’s board of trustees, the faculty trustees and student trustees received an email from Davidson telling them not to come to the meeting because it would be an “executive session for elected trustees [pdf] only. This session will be exclusively devoted to completing the discussion from the October 2016 meeting, regarding the renewal of President Wilson’s Employment Agreement.”

It was a slick move. Bob Davidson had tabled the October vote on Wilson’s contract until January, then kicked the students and faculty trustees out of the January meeting.

Johnathan Hill and the student trustees weren’t having it.

Hill was a Morehouse fighter. He had heard and read stories about this same thing. Forty-eight years ago, a Morehouse student held the entire board of trustees hostage. The student was so upset about the board’s lack of representation, he locked the board members, including Martin Luther King Sr., in a building during a board meeting. Morehouse suspended that young student from campus, but he was eventually allowed to return and graduate. His name was Samuel L. Jackson.

Hill called his mom and warned her what he was about to do: “I was so scared because I knew my mom would flip out if I was kicked out of school.” He showed up at the meeting and demanded to speak with the board chair. According to Hill—both in conversations with The Root and sworn affidavits (pdf)—when he entered the room where Davidson had invited him, there were “seven or eight” other trustees waiting, and Davidson told Hill that he would allow him to be part of the discussion and vote on Wilson’s contract—only if Hill told him how he was going to vote.

Johnathan Hill and the Morehouse students decided to fight.

Hill, Moses Washington and Johntavis Williams—the other student trustees—hopped into a car and sped to a courthouse. Theirs was the last court case to be heard that afternoon, and just before the end of the day, Morehouse College’s student leaders walked in front of a judge and filed a temporary restraining order against Robert C. Davidson.

Despite student protests, faculty objections and a correspondence from a retired judge (pdf) warning the board that the school of Martin Luther King was ostensibly engaging in voter suppression, Davidson didn’t care. He kept the students out and proceeded with the vote. When the meeting resumed the next day, Chairman Davidson allowed the faculty and student trustees to attend. All discussion regarding John Wilson had already taken place. The board had already voted not to renew his contract.

Hill wasn’t finished fighting, though. He and other students filed an injunction (pdf) to legally force Davidson into calling another board meeting, but a judge dismissed the order Feb. 13, 2017. Two days later, on Feb. 15, a select group of faculty members met with board members to express how they felt about being excluded from the college’s decision-making process. According to faculty members present at the meeting, Bob Davidson didn’t show up.

On Feb. 27 and 28, Donald Trump met with dozens of HBCU presidents at the White House, including John Wilson. After the meeting, while other black college presidents said very little about the gathering, Wilson—having recently been fired, with a résumé that included working for HBCUs from within the White House—was the first HBCU president to speak out to express doubt and concern. Then Wilson flew back to Atlanta to meet with his faculty.

After Wilson met with the faculty and took questions and answers March 2, the faculty penned a March 5 letter to board Chairman Robert Davidson requesting three things (pdf):

- A meeting with the faculty like the one he had recently not shown up for.

- That the board should void its decision to fire Wilson.

- A discussion and revote that included all of the faculty and student trustees.

The letter circulated among the Morehouse faculty for signatures on March 6. On March 6, without contacting Wilson, the faculty or student trustees of Morehouse, Chairman Davidson issued a statement saying that William “Bill” Taggert would begin to assume day-to-day responsibilities for the college. Media outlets (including The Root) interpreted the statement to mean that John Wilson was gone—effective immediately. The next day, Wilson sent an email to Morehouse faculty, staff and students reassuring them that he remained president.

But who can be sure? Robert C. Davidson has shown that he has veto power over every decision at the school, and John Wilson is a lame duck who is president in name only. If Davidson can silence the student body, suppress the votes and voices of the faculty, and engineer the ouster of the man who saved the school, who is in charge at Morehouse?

Before completing this story, we offered John Wilson and Robert C. Davidson a chance to speak with The Root. They declined. We sent each of them a list of questions in writing to see if they would answer. We received acknowledgment of receipt of the letters from Morehouse staff members, but we have yet to receive a response.

Morehouse is in limbo once again. Multiple faculty members have expressed concern about whether Apple will follow through with the grant now that Wilson is gone. Zimbabwean billionaire Strive Masiyiwa resigned from the board of trustees. Michael Polk (CEO of Newell Brands) quit, too, as did Ralph de la Vega (former vice chairman of AT&T).

Over the course of reporting this story, every single voice we heard expressed his or her unwavering love for Morehouse. In an age when Morehouse must now compete with better-funded schools like Harvard, Stanford and MIT, they each reiterated how much black America and this country need Morehouse. They believe it to be an American treasure this nation cannot afford to let die:

HBCUs are at a point where women’s colleges were in the ’70s, and if there is one institution in this country worth fighting for, it’s Morehouse. —Morehouse faculty member

Morehouse’s place in the American zeitgeist is crucial because of its mission in building and developing a space where black people can participate in the experiment that is American democracy. —Morehouse faculty member

Morehouse is the answer to why black lives matter. —Johnathan Hill, Class of 2017

Johnathan Hill will graduate from his beloved Morehouse soon, and with his spirit and ethos, he is sure to conquer the world. Morehouse has a world-class faculty who could work anywhere they chose. John Sylvanus Wilson has a stellar résumé and will easily find another job. Robert C. Davidson’s tenure as chair of the board of trustees expires this year, but after stacking the body with alumni, he is sure to have some semblance of control.

But what about Morehouse?

We have seen this kind of infighting before—perhaps too many times. Whether it is the pastor-deacon board disputes that fracture country churches, or the mismanagement that capsized Morris Brown, this is too familiar.

We are often ambivalent in the face of dire circumstance and take for granted our future survival because of black America’s historic resilience and perseverance. But we cannot allow Morehouse to cannibalize itself—it belongs to all of us. Even if you have never stepped foot on the campus or slept in the dorms, from her womb sprang a lineage of men that have entertained, protected and fought for all of us.

We cannot bare our teeth at the predators but remain silent when the threat to our people comes from within. It is not always the wolves. Sometimes it’s the sheep among us. In this age of resistance, John Wilson was bold enough to stand up for Morehouse in the face of the leader of the free world. Now someone must stand up for him, or sit back and watch a national treasure be devoured.

We owe it to black America.

We owe it to America.